Not long ago, I used this space to talk about Worlds Unknown, an effort by Marvel Comics to adapt notable prose science fiction into comic book form. DC has also explored this idea, using a format that isn’t seen as often as it used to be, the graphic album.

Not long ago, I used this space to talk about Worlds Unknown, an effort by Marvel Comics to adapt notable prose science fiction into comic book form. DC has also explored this idea, using a format that isn’t seen as often as it used to be, the graphic album.

What’s a graphic album? It’s a paperback book, roughly square in size, and a bit larger than a standard comic book. It used to be—and maybe still is—a popular format in Europe, so when American publishers started to print paperback comics, this is where many of them started.

From 1985-87, DC published seven volumes in its SF adaptations series. They were edited by Julius Schwartz, a man who could be called legendary without exaggeration or fear of contradiction. As an editor, Schwartz supervised the reintroduction of DC’s super heroes in the early 1960s, among other accomplishments. Before that, he was one of first generation of science fiction fans, a literary agent in his teens and one of the organizers of the first world science fiction convention.

I don’t have all seven books in this series, but my favorite of the ones I do have is the adaption of Robert Silverberg’s Nightwings, by Cary Bates, Gene Colan and Neal McPheeters. For those unfamiliar with the original story, Nightwings is set in the far future, on an Earth where life and advanced technology are slowly fading away. It’s a moody and evocative story that avoids most of the clichés connected with this type of fantasy. It won the 1969 Hugo award for best novella.

Colan’s art skillfully combines the fantasy and the sf elements in the story, with his mastery of faces and emotions. Bates’ script captures the flavor of the original, without making this version text heavy.

The next book in the series was an adaption of a short story by Frederik Pohl, “The Merchants Of Venus.” With a Pohl byline, and the words “merchants” and “Venus” in the title, you might be thinking this story is connected somehow with The Space Merchants, the classic novel Pohl wrote with Cyril Kornbluth. You would be wrong, but it’s a reasonable assumption to make. It is, in fact, the first appearance of the Heechee, a race of ancient extraterrestrials who play a role in several of Pohl’s books.

McPheeters handles the art chores himself this time, and co-writes the script with Victoria Peterson. His solo art is looser and more cartoony than his work in Nightwings. It’s a daring look for a comic now, and was probably even more so in the late 1980s.

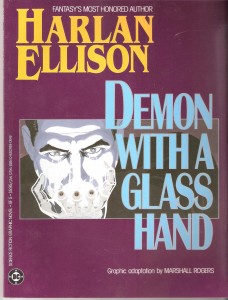

I‘ve been calling this series adaptations of prose sf, but that’s not entirely true. One of the albums is an adaptation of Demon With a Glass Hand, a television script that Harlan Ellison wrote for The Outer Limits in the mid-1960s. Ellison’s run-ins with TV producers are well-known, and it looks like “Demon” had its share of problems too. However, you have to look at the small print on the inside front cover to see that this version is “the original author’s version, not the rewritten shooting script.”

The title character of this story is a man named Trent, who discovers he has been sent back through time to the 20th century (you can’t call the 20th century the present any more) for reasons unknown. He is being pursued by an alien race called the Kyben, for the aforementioned reasons unknown. The only way he can find out why he’s been targeted is by reassembling the components of his glass hand, which is an advanced computer.

The title character of this story is a man named Trent, who discovers he has been sent back through time to the 20th century (you can’t call the 20th century the present any more) for reasons unknown. He is being pursued by an alien race called the Kyben, for the aforementioned reasons unknown. The only way he can find out why he’s been targeted is by reassembling the components of his glass hand, which is an advanced computer.

The art here is by Marshall Rogers, who rose to prominence with his work on Batman. He sticks to the script very closely, down to using the ominous opening narration that the TV show used and dividing the story into four acts.(An hour-long adventure show was usually divided into four acts in the 1960s; I think the modern format calls for five acts.) He also does a good job at capturing the claustrophobic atmosphere of the TV episode. As you may know, this story was filmed at the Bradbury Building in Los Angeles, a gem of art deco design that is used in Blade Runner, among other movies and TV shows. The look of Bradbury Building works well with Rogers’ love of intricate architecture, and he takes full advantage of it.

The other books in this series were: Hell On Earth, a Robert Bloch story adapted by Robert Loren Fleming and Keith Gifften; Frost and Fire, a Ray Bradbury story adapted by Klaus Janson; The Magic Goes Away, a Larry Niven story adapted by Paul Kupperberg and Jan Duursema and “Sandkings,” a story by George R. R. Martin, adapted by Doug Moench; Pat Broderick and Neal McPheeters.

In his memoir, Man of Two Worlds, Schwartz offers the following assessment of the series: “In retrospect, maybe we should have led off the lure of an Asimov or a Clarke or a Heinlein or even a King to attract more attention to the series. Unfortunately, our different format wasn’t really comic-shop friendly…and, at that time, the book trade shied away from graphic novels, thus limiting our distribution. It was a bold experiment and a good effort, but it didn’t work…”

Recent Comments