Normally in this space I rattle on about pulp magazines. Today we’ll look at a different type of periodical: comic books.

Normally in this space I rattle on about pulp magazines. Today we’ll look at a different type of periodical: comic books.

Or, if you will, graphic narratives.

More specifically, we’ll examine the work of one particular comic book artist: Tony Harris.

Pulp magazine characters haven’t always translated well to the comic medium. The characters aren’t quite super enough to grab the attention of dyed-in-the-spandex superhero fans, and dedicated pulp hero fans usually find some discrepancy between the canonical prose version of their hero and its comic incarnation to nit-pick the bandes dessinees doppelgangers to death.

So — despite some standout runs in comic book pages — the Dennis O’Neil/Mike Kaluta performances on The Shadow come to mind (actually, The Shadow seems to have fared better than other pulp heroes in the spandex jungle) — this uneasiness in stepping from one storytelling medium to another helps explain why these licensed properties hop from publisher to publisher.

So (two paragraphs in a row starting with the same words — not a good habit to start), why talk about a comic book artist in relation to pulps?

Tony Harris hasn’t (to my limited knowledge) tackled any pulp characters in his career as a narrative artist. But his work, at its best, displays a bravura energy that manifests in a visual manner the type of adrenaline-rushing thrills that certain pulp-era fictioneers strove to imbue in their prose.

Harris first made his mark in the popular consciousness as the regular artist — one might even say co-creator — on DC Comics Starman with writer James Robinson. The latter’s great love for DC’s classic characters — which readers of a Certain Age would call National Periodical Publications’ Earth 2 heroes — is evident in his work; indeed, he’s been the primary scripter for the Earth 2 line of books published since DC’s most recent line-wide reboot. He brought this love and a sense of the character’s historic continuity to the monthly adventures of the original Starman’s son.

Harris complemented Robinson’s words with dramatic drawings featuring art deco-influenced decorations and what might be described as a vintage look and feel for a contemporary story. The atmosphere Harris created — through backgrounds, costuming, panel arrangement and design — gave the book an authentic dressed-in-vintage feel. (One may say Harris dressed the Starman book in the way a Hollywood designer creates the look and feel of a film for a director and cinematographer.)

The artist’s next long run was on Ex Machina, a contemporary superhero/politician story published by DC under its Wildstorm imprint. Harris’ art was just as dramatic and unique as it had been on Starman, but his reliance on photographic models — while appropriate for the type of story he and Brian Vaughan were creating — removed some of the interesting edge from the work, in my opinion.

“Where’s the pulp?” you ask. Okay, let’s get to that.

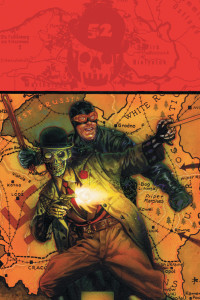

For several years, DC has been publishing non-canonical, non-continuity-based stories featuring their characters under the Elseworlds umbrella. “In Elseworlds, heroes are taken from their usual settings and put into strange times and places — some that have existed and others that can’t, couldn’t or shouldn’t exist.” In 2000 and 2003, Harris drew two mini-series co-scripted by Dan Jolley: these were collected into a single volume in 2004 as JSA: The Liberty Files.

These stories placed versions of the Justice Society in World War 2 and post-war Europe. But the slick, polished look of the heroes was replaced by Harris with clumsier versions of their costumes — something more closely resembling a “realistic” look, if one can imagine such during the WW2 era. The super characters were loosely joined as a group of special intelligence and espionage operatives battling similarly morphed versions of familiar villains like The Joker, The Space Parasite, and Kryptonian General Zod.

The depiction of the characters — primarily Batman, Hourman, Mr. Terrific, and Dr. Mid-Nite — is not so different from what a pulp hero reader might have seen in a comic book version of his heroes if such a book were created with a 21st Century sensibility. A gritty, street-level view of the heroic characters that revels in their human capabilities is apparent here; the larger-than-human gods-in-spandex players at cosmic chess who fly across the canonical comic pages today are brought back down to human scale by Harris and Jolley in these stories.This refreshing take on familiar faces brings the comic book characters far closer to the pulp types that influenced their creations than they’ve appeared in decades.

Harris’ style here is not the slick, polished look we’ve come to expect in superhero books. It is, instead, bold and almost raw — the lines are thick, the characters sometimes captured in ungainly poses that accentuate their human elements. There is both gravity and energy in these drawings — energy that Harris restrains until he releases it in remarkable bursts of action set pieces. The raw power in these visuals captures masterfully the rushing crackle readers still find in the best of the pulp hero prose from the heydays of Doc Savage, The Spider, Carroll John Daly’s Race Williams, and Black Mask author Paul Cain.

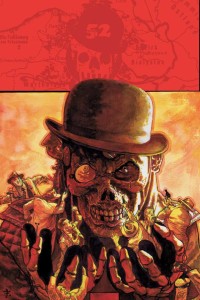

More recently, Harris returned to this storytelling era with B. Clay Moore for The Whistling Skull, a 6-issue mini-series published by DC under the JSA Liberty Files banner. The eponymous Skull is a comically grotesque-looking hero working in Europe to thwart Nazi advances. The current Skull is just one of a long line of Skulls (similar to Lee Falk’s Phantom), and the current Skull can pull on the memories of all the past, departed Skulls.

More recently, Harris returned to this storytelling era with B. Clay Moore for The Whistling Skull, a 6-issue mini-series published by DC under the JSA Liberty Files banner. The eponymous Skull is a comically grotesque-looking hero working in Europe to thwart Nazi advances. The current Skull is just one of a long line of Skulls (similar to Lee Falk’s Phantom), and the current Skull can pull on the memories of all the past, departed Skulls.

Harris’ art here is just as bold – perhaps more so, as it seems he’s pulled no punches by tying his work to photographic models. The lines are thicker, the POV wheels about for the individual panels on any given page, demonstrating (to return to the film-making analogy) a love of fluid camera movement as dynamic as that of Orson Welles and Abel Gance. As in his Starman work, the page design demonstrates a fusion of Art Deco, Nouveau, and Futurist influences wrapped up in a 21st Century graphic narrative sensibility. Harris tells his story with a sort of artistic whiz-bang fever that is communicated through the drawings by the way they capture the earnest rawness of folk art. Harris’ use of heavy blacks almost suggests the solidity one feels in woodcuts from the Middle Ages. The effect is quite remarkable in a comic book.

And Harris’ covers for each of The Whistling Skull issues? They wouldn’t have looked out of place on a pulp-era newsstand alongside Terror Tales, Dime Mystery, Weird Tales, or The Spider.

After Harris moved on from Starman, he worked from photographic models for a while, as mentioned earlier. As a result, his depictions of characters have progressed to being less glamorously handsome than is typical in most comics. Indeed, the faces of nearly every character in The Whistling Skull stories may be said to be on their way to a Fellini film casting call. These folks have everyday faces any reader would see passing on the sidewalk: these are the faces of normal people, not gods-in-spandex. This authenticity gives Harris’ work an honesty, a centered gravity — even though he’s working in a highly unrealistic genre.

The boldness of Harris’ art, coupled with its realistic earnestness, allows him to depict convincingly the heightened melodrama required by these kinds of tales. He’s transported these qualities well to his latest project, Chin Music, written by 30 Days of Night’s Steve Niles and published by Image Comics.

Another period piece, this story combines The Untouchables with The Abominable Dr. Phibes. Harris employs heavy blacks, deco-inspired designs, and a gritty spontaneity that make these pages wonders to behold.

Again, and throughout his career, Tony Harris has delivered work that epitomizes — in a different medium — the adrenaline-laced wildness of the prose hammered out by pulp fictioneers like Norvell Page, Carroll John Daly, Paul Cain and Lester Dent. He entertains and dazzles. You may turn a page and be gob-smacked by what you find. You’ll finish an individual issue and turn back to the first page to start scrutinizing what you just sped through. You’ll want the next issue to appear. Now.

That’s the magic of Tony Harris. The 21st Century Pulp Artist.

Recent Comments