Christopher Priest is one of the leading authors in any genre. His first published story was ‘The Run’, in 1966. His first novel, Indoctrinaire, was published in 1970. His second, Fugue for a Darkening Island, was a Campbell nominee, while his third, The Space Machine won the British Science Fiction Association (BSFA) Award and was nominated for a Hugo. A Dream of Wessex (1977 – published in the US as The Perfect Lover) is arguably the first great virtual reality novel.

Christopher Priest is one of the leading authors in any genre. His first published story was ‘The Run’, in 1966. His first novel, Indoctrinaire, was published in 1970. His second, Fugue for a Darkening Island, was a Campbell nominee, while his third, The Space Machine won the British Science Fiction Association (BSFA) Award and was nominated for a Hugo. A Dream of Wessex (1977 – published in the US as The Perfect Lover) is arguably the first great virtual reality novel.

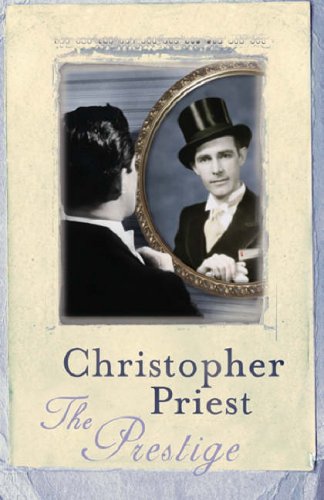

The Prestige won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, the World Fantasy Award and was adapted into a hit film directed by Christopher Nolan and starring Christian Bale, Hugh Jackman, Michael Caine, Scarlett Johansson, Rebecca Hall and David Bowie. Priest’s three most recent novels, The Extremes, The Separation and The Islanders, all won the BSFA Award. The Separation won the Arthur C. Clarke Award and The Islanders the Campbell Award.

In this, the first part of a two part interview, Christopher Priest talks about his new book, The Adjacent.

*

There are some books, the less you know about them when you start reading, the more enjoyable and rewarding the experience. The Adjacent, is one such. The only problem with not knowing anything about a book is knowing whether you want to read it. Even the back cover of the uncorrected manuscript proof I received of The Adjacent was unusually reticent: The Adjacent is a novel where nothing is quite as it seems. Where fiction and history intersect, where every version of reality is suspect, where truth and falsehood like closely adjacent to one another. It shows why Christopher Priest is one of our greatest writers.

*

GARY DALKIN FOR AMAZING STORIES: Christopher Priest, welcome to Amazing Stories. The Adjacent is your most ambitious and complex novel so far. Given the discretion of the publicity material, how would you introduce it to potential readers?

GARY DALKIN FOR AMAZING STORIES: Christopher Priest, welcome to Amazing Stories. The Adjacent is your most ambitious and complex novel so far. Given the discretion of the publicity material, how would you introduce it to potential readers?

Christopher Priest: I never really know what to say about a book once I’ve finished it. Years ago, the publisher asked me to suggest a blurb for The Prestige. I struggled all day with it, and finally came up with a mouthful of worthy but boring stuff about obsessive secrecy and loss of identity. Years later I realized I should just have said: “It’s about two 19th century magicians trying to destroy each other.” I try to learn from past errors, but even now, a year or so since I finished the book, I’m not really sure what The Adjacent is about. The story begins with a man whose wife has been murdered in unusual circumstances, and he’s hurt and upset by it, but as you know that doesn’t give even a hint of what is to come.

I agree with your general proposition that books are often enjoyed more when you know less about them, but publishers want to give away the best bits. Maybe they know better than writers? But I think they should just leave the writer to tell his or her own story in the way they know best. Back in 1971 I read John Fowles’s The Magus in a paperback edition from which the covers had been torn off (the friend who lent it to me hated Michael Caine, whose face was on the cover), so I hadn’t the faintest idea what was in store. Reading the novel “blind” like that turned out to be a memorable experience. I’d rather like people to discover The Adjacent in the same way … so I’m glad to learn the blurb you saw was so reticent.

ASM: There is something you do in The Adjacent which is different to anything you have done in the past. Many respected writers associated with the science fiction field have, a considerable way into their careers, revisited earlier works with new sequels and/or in some way attempted to link their past works together into a ‘future history’. There is something of this in The Adjacent, not in any overtly commercial way, but as part of the very nature of the novel. Your previous works become literally ‘adjacent’ to the new book in that it contains many references, some of which I doubtless missed, to just about everything you have ever written.

There are, for instance, allusions to twins, to invisibility, to stage magic (it’s an interesting coincidence that Michael Caine would so many years later be one of the stars of the film version of The Prestige). A character from The Separation is mentioned, though does not appear. There is even the appearance of a character from one of your earliest novels, The Space Machine. Is it possible to say something about all of this without saying too much?

CP: I don’t feel too secretive about it. In any case, attempts to keep your plot to yourself get blown away with the first review, and readers do like to know a bit about what they’re in for.

About the references. There have always been links between various things. The Affirmation, The Quiet Woman, The Islanders and a novella called ‘The Miraculous Cairn’ are already tenuously linked, and the Dream Archipelago material is loosely connected, of course. And I felt I was careful, in The Adjacent, to make these references a harmless bonus if you spot them, but you’re not missing anything if you don’t. I don’t want readers to think it’s a puzzle they have to solve. It’s a self-contained story.

About the references. There have always been links between various things. The Affirmation, The Quiet Woman, The Islanders and a novella called ‘The Miraculous Cairn’ are already tenuously linked, and the Dream Archipelago material is loosely connected, of course. And I felt I was careful, in The Adjacent, to make these references a harmless bonus if you spot them, but you’re not missing anything if you don’t. I don’t want readers to think it’s a puzzle they have to solve. It’s a self-contained story.

Yes, it’s a coincidence about Michael Caine. Unlike the friend who lent me The Magus, I didn’t have strong negative feelings about the great man, but when I met him at the London premiere of the film he refused to talk to me. “I never talk to writers,” he said, and backed off looking cross.

AMS: I wonder what Michael Caine has against writers? They’ve given him his career and made him a lot of money over the years!

I didn’t see The Adjacent as an attempt to retro-fit consistency. Rather the opposite, in that if noticed the little references in The Adjacent perhaps undermine the reality of previous books a little more than those books already undermine themselves. But a reader could come to The Adjacent not having read any of your previous work and thoroughly enjoy it, unaware of any connections. It’s probably fair to say that new readers and long-time Priest readers will see it in different ways.

At one point one of the narrators in The Adjacent says: ‘Audiences who go to magic shows often see themselves as engaging in a kind of undeclared contest with the performer, constantly seeking to spot what he is ‘really’ doing. These audiences are, paradoxically, amongst the easiest to misdirect because in their eagerness to catch the magician out they concentrate on all the wrong actions.’ Is this true of some of the readers of your books? There is a tendency to look for significance in all the wrong places while the story is going on elsewhere?

CP: I’m really trying to do a simple but familiar thing in a new and I hope intriguing way. I’m a writer of narrative. My impulse when starting any book is to tell a story, one with a proper beginning, a proper middle and a proper ending. (And in that order, to reverse the familiar Godard joke.) The prospect of a proper beginning is what gets me started, and the feeling of heading towards a proper ending is what keeps me going. This is the simple intent. I love story, the feeling of characters and events and language taking shape, piling up around me, gradually forming themselves into a narrative.

Some of this is a conscious process, but much of it is freeform, and develops naturally from the characters. For example, in The Adjacent I wanted to tell the story of Krystyna Roszca. It’s a straightforward account of a young woman surviving somehow through one of the great upheavals of recent history. I knew before I started writing her narrative what Krystyna’s background was going to be, what would happen to her and what she would probably do about it. I also planned her eventual fate. But once I started telling her story, through the eyes of the young man who meets her, a whole world of revelation opened around me … not just about Krystyna and her story, but about the shape of The Adjacent itself, her role in the novel, her crucial impact on the way it turns out. I created her consciously and deliberately, but obviously something deeper was churning away inside, something I only discovered by writing about her.

So that’s the familiar bit, and I suspect a lot of writers would probably say much the same. Writing narrative is an intriguing thing for me: you feel you are pushing it along, but somehow at the same time it is pulling you back.

I’m also interested in story structure. For years I’ve believed that the fantastic novel (my slightly evasive alternative name for science fiction) is an ideal place to try out some new ideas about form. Most SF is surprisingly conventional in form, when you think about it. The O. Henry type of twist-ending short story, the cliffhanger episodic novel, the romantic voyage, the quest saga, the revenge thriller, the mystery, the story of exploration and discovery. These are all tired, overworked forms, done to death. But here we are, as writers of the fantastic, dealing with some of the most stimulating material in modern fiction. I love the fantastic metaphor, the startling idea, the novelties, the sheer intellectual thrill of trying to imagine the unimaginable and describe the indescribable. This surely is the game we are playing? Shouldn’t we be looking for equally adventurous ways of structuring what we write?

So getting back to your question about misdirecting the reader. I felt The Prestige was implicitly about that. That novel used performance magic as an extended metaphor for the writing of fiction. But it’s not what I usually do. A novel is text, words on a page, clear to read and plain to understand. The reader makes of the words what he or she will — I often say that the act of reading is a creative one, not entirely dissimilar from the act of writing. Everyone reads a novel differently. We imagine the places, the characters, the tone of voice, the intents, the underlying prejudices, in our own way. So it’s difficult for the writer to pull the wool over the reader’s eyes. However, when you accept that language itself is full of different meanings, that people in everyday life employ understatements, hints, fudges, falsehoods, they misremember details, they are embarrassed about something, or they are unable to face up to the truth, or they are trying to manipulate a response, or depict themselves in a good light, or are trying to undermine someone else … then writers are simply not doing a proper job unless literature itself invokes these shades of meanings.

*

Christopher Priest: The Adjacent Interview – Part 2 will be on Amazing Stories from 20 June, the same day as The Adjacent is published in the UK. Meanwhile visit Christopher Priest online.

2 Comments