[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5cn4A5IZg1k&w=570&h=321]

Having seen Star Trek Into Darkness twice now, and having very much enjoyed it, my aim is to avoid spoilers here whenever possible, for the sake of those readers who might intend to see the film but haven’t gotten around to it yet. That said, if you’re really worried about it, I’d say close your browser now and get to the nearest cinema. It’s a movie well worth your time (and money)—and is perhaps the best space opera film since 1980’s The Empire Strikes Back.

It isn’t perfect, of course. There’s been a bit of backlash over the controversial racebending of one especially beloved Trek character. And Captain Kirk’s womanizing is in full force, despite the six or seven years that have elapsed since the last Abrams Star Trek picture. Damon Lindelof even issued an apology for the gratuitous, half-nude Carol Marcus (Alice Eve) scene.

The film also features a few eye-rolling moments of scientific impossibility played out casually and without alarm or explanation. Not that you really expect a Star Trek movie to be free of such “artistic liberties,” you understand, but nevertheless they are noticeable.

But what I took to be profoundly bold, and dealt with in a tasteful, mature manner, is the film’s commentary on post-9/11 jingoism and the culture of fear that has taken root in the West in the aftermath of George W. Bush’s presidency. There are two principal villains in the film: one alienated from his homeworld, whose motivations are at times hard to grasp; and one who holds high office in Starfleet, whose actions and authority make clear his warmongering agenda.

I’d argue that Into Darkness’s plot is not deeply allegorical, but rather an intelligent exploration of our notions of good, evil, and the whole spectrum between—of our notions of deterministic destiny, choice, and justice.

Back when the news hit of Osama bin Laden’s assassination by SEAL Team Six, I recall feeling a deep sense of dissatisfaction. What had we gained? An alleged corpse. The great CIA story that became Kathryn Bigelow’s 2012 zeitgeist film Zero Dark Thirty. Was it justice? I’m still unsure.

At the time, I was taking a mandatory college course, called Reflections: Suffering, Evil, and Hope. When the professor asked for our gut reactions to the terrorist’s death, I was the minority opinion. The only one, in fact, who was not elated at the news of bin Laden’s death. Later that day, I said to my ethics and philosophy professor, Dr. C. Hannah Schell, “We’re bloodthirsty,” meaning we as a nation. As a Western way of life: Our culture of fear.

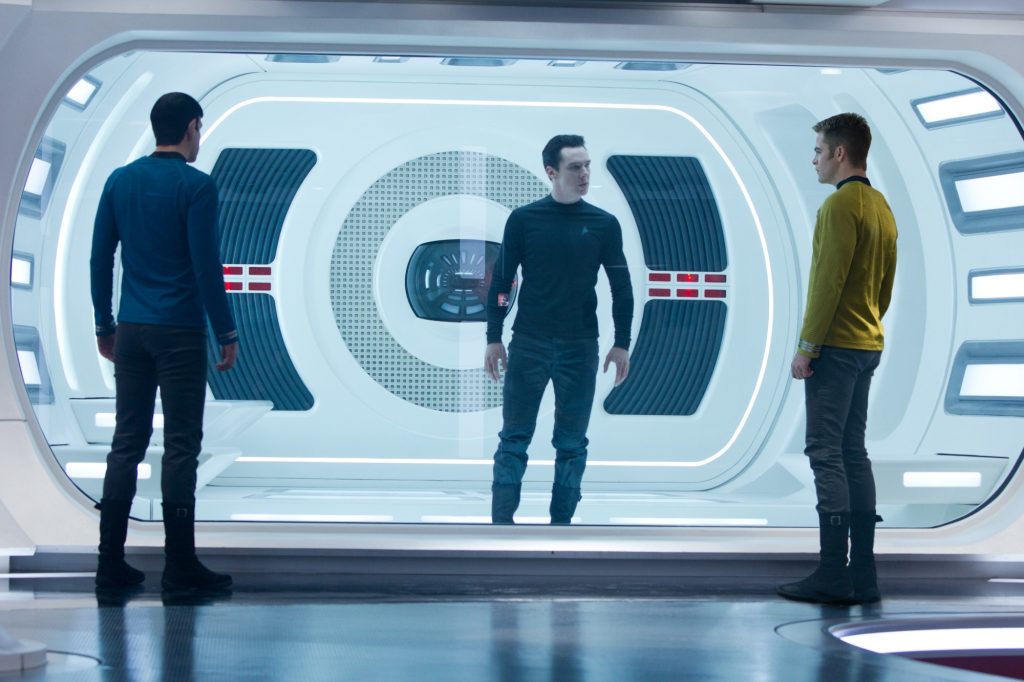

Spock (Zachary Quinto) remarks to Captain James T. Kirk (Chris Pine), in Alan Dean Foster’s novelization of the Star Trek Into Darkness script,

“While I harbor only the ultimate disdain and contempt for the individual known as John Harrison, and desire strongly that he receive the punishment due him, I must point out that there is no Starfleet regulation that condemns a man to die without a trial—no matter how egregious his offenses.” (Kindle e-book edition, Simon & Schuster)

I believe in the final, filmed version of Quinto’s dialogue, Spock instead adds something to the effect of, “—a fact which you and Admiral Marcus seem to be forgetting.”

It seems fairly evident that screenwriters Roberto Orci, Alex Kurtzman, and Damon Lindelof saw the villainous John Harrison (Benedict Cumberbatch) as an opportunity to explore not only the growing threat of domestic terrorism, but also the problems that arise from institutionalized revenge—thanks, perhaps, to the troubling politics at play in American foreign policy.

When Kirk, Spock, and Lieutenant Nyota Uhura land via shuttlecraft on the barren, warlike planet of Kronos, it quickly becomes evident that the Klingon race is a stand-in for the political and cultural other. Most likely, given the subtext of more or less every quasi-political Hollywood film of the past decade, for the Middle East in particular.

The irony at play in this action-heavy sequence is that Uhura warns of the Klingons’ capacity for torture and murderousness; then, after Harrison intervenes by opening fire upon them in the middle of her efforts at diplomacy, she proceeds to draw the blade of the Klingon warrior in front of her and stab him in the leg.

The Klingons as a group are discovered to be far less of a threat than the former Section 31 agent Harrison, despite Admiral Marcus’s earlier insistence that war with Kronos has become increasingly inevitable. Yet they’re the ones Kirk’s crew has been ordered to attack.

In other words, Star Trek Into Darkness shows the manner by which we tend to place all blame for any grave injustice not upon entire nations, or specific political blunders, but instead upon a single human scapegoat, regardless of how dubious or vague the facts surrounding a particular conflict prove to be. Even if the war itself ultimately has little to do with the one declared responsible.

We want quick gratification. A name and visage toward which to direct our collective hatred.

But with tears streaming down his face, something truly haunting Harrison behind those chilly eyes of his, we can’t help but question the narrative at play. Question our justifications for even the most clear-cut of wars. There are those who assert, for instance, that the organization known as al-Qaeda is little more than a fiction of the English-speaking world’s media. Where that’s true or not is irrelevant: Either way, we need a humanistic, peacekeeping force like Starfleet—like the United Nations, like Amnesty International—to propagate the gifts of peaceful coexistence, understanding, and, most importantly, the idea of forgiveness.

Abrams’s Into Darkness forces us to give pause, and reconsider the motivations at play behind militaristic campaigns and their xenophobic leaders—the “Masters of War,” as Dylan calls them.

As Captain Kirk reflects in the film’s ending, to seek revenge upon wrongdoers is to risk losing our own sense of right and wrong. In Foster’s novelization, the captain goes on to say in his speech,

“We are gathered here to pay our respects to fallen friends and family. We take solace in the knowledge that we honor those who lost their lives doing what they believed was right. And no matter what path they took, we hope that in death they can find forgiveness.” (Simon & Schuster)

That is something I fear we may be hard-pressed to find in the Western world, even twelve long years after the atrocities of September 11, 2001. To forgive is such a foreign concept to us. And yet in a sense, sealing Harrison away in cryostasis is a sign that we’re somehow, as Kirk would put it, getting better—but as a nation whose deep-seated ideologies stem from the war crimes and bomb scares and genocides of the twentieth century? Well, we still have so very far to go.

I applaud the filmmakers and studio heads at Paramount and Bad Robot not only for being willing to admit this, that our collective kind hasn’t quite learned to forgive and get along with one another, but also for having the fullness of vision to dedicate the movie and its bold message to those brave souls who have served among U.S. and NATO Coalition forces in the wake of that single, unforgettable morning that shook the innocence from our once-great nation forever.

I meant to write “that was consistent with Gene Roddenberry’s ideals.” He had firm ideas on what was okay to portray in his universe. He had a utopian view of the future.

What the hell happened to Bones? the brilliant and sarcastic doctor,de Old generation is now a sort of clown. And the shadow of Ricardo Montalvan is too big … I still enjoyed it for something I am a fan.

Hi Alex – –

Well your blog is more than a small mouthful, but I’m going to tackle it anyway. First of all, it’s probably important to point out that Star Trek: Into Darkness is just a movie.

Having said that, there is some truth to the fact that science fiction fans do like to exercise their grey matter. Finding reality within the parameters provided by fictional stories has long been a valid means of discoursing the truth. We can’t just discuss political truth in America anymore. Political correctness, political polarization, the Patriot Act, and numerous cultural barriers has forced the American cultural landscape to mature. So I suppose we have to look at cultural phenonemon (like films with worldwide releases) with greater scrutiny because they really do say things about us as a culture.

But this goes far beyond the intent of the film’s producers, doesn’t it? Is it fair to them? Maybe it is. If Damon Lindelof feels it’s important to apologize for a sexually provocative Carol Marcus, for public relations reasons, (when the original Star Trek so often pushed the limits of fashion) then perhaps we must acknowledge that Star Trek movies are more than just a movie. If the movie’s themes have an impact on our society’s values, we have to recognize that the movie isn’t just a movie anymore, but a self-defining instrument of social engineering.

Do we want that?

In a discussion of good and evil, you seem to imply that these Star Trek villians may be unwittingly defining our human nature. Have our expectations of a Star Trek movie risen so high that we have to rule a movie “only as entertainment” as somehow socially unacceptable?

I’m still grinning about the tongue-in-cheek Spock screaming “Khaaaaannn!” I’d hate to think a franchise would have to forego a cheesy laugh in favor of social engineering requirements.

Thanks for reading, Jay.

—–In a discussion of good and evil, you seem to imply that these Star Trek villians may be unwittingly defining our human nature. Have our expectations of a Star Trek movie risen so high that we have to rule a movie “only as entertainment” as somehow socially unacceptable?—–

Do you live on the same planet that I have? People who want a movie to have some sort of intelligence usually are forced to apologize for that.

The American landscape has been forced to mature? Really? I …. don’t see that at all. I’m not sure I understand your post actually. Are you saying that he’s wrong to read those issues into the movie? Or are you, um, suggesting he shouldn’t talk about them?

I really have no idea what your saying.

Well Michael, I’ll try to clarify my comment.

Just because a movie-goer reads something into a movie doesn’t mean it’s there.

You can use it as a spring board for discussion, but I really don’t think JJ Abrams intent was to discuss jingoism or torture in the movie. Maybe the movie has unintended consequences … but that’s on the viewer. Not the movie maker.

I’m not a fan of social engineering and I don’t think the filmakers were doing anything but making a good movie. I’m happy that the franchise is going in a positive direction. From what I gather in your comments, you apparently don’t think so.

Not a fan of social engineering? So if an author talks about something that can be construed as meaning something, that’s social engineering? I had no idea it was so simple to engage in social engineering.

Gene Roddenberry himself, by that definition, also engaged in social engineering, and to a much greater extent. He had a lot of ideas about what a future society would be like, and he felt strongly enough about it to clash with Harlan Ellison over “The City on the Edge of Forever.” So if all that is bad, I guess you shouldn’t like the franchise at all.

Generally speaking, I don’t like rebooted franchises, though I occasionally watch them. I would prefer that new generations created their own stories rather then just constantly remaking old ones, and Hollywood has done far too much remaking lately.

I found seeing the movie to be an incredibly strange experience, partly because I am a fan, and I found the crew to just be utterly unconvincing. I don’t feel that the guy playing Spock has the presence for the role, and Uhura was incredibly annoying. The guy playing Kirk actually worked better for me, which surprised me.

McCoy was simply there to ape McCoy’s conversational style, and he didn’t really do anything else. It’s like the whole thing is JJ Abrams funtime playset. He gets to recast all the old characters, and the fans ooh and ah as they recognize the tropes. To me it just felt weak.

I actually was relieved to see the thing on torture raised. It’s probably one of the few things that’s happened with the movie that was actually consistent with his own ideals. He had a certain vision of how the universe was, and I think he would liked the fact that his movie made a statement about torture and assassination. It wouldn’t have been necessary once, but many Americans actually think torture is ok now, so it actually is current.

The tragedy is, twenty years ago I would have thought it was a silly thing to say, because everybody would feel that way. Now, it’s actually a gutsy position to take, and people like Jay apparently feel terribly put upon that someone would suggest in a movie that torture and assassination are bad things.

Don’t worry Jay, there will be many, many more pretty explosions coming to a theater near you soon.