I had given some thought to doing an Oscars recap this week, tallying the various gains and losses of the science fiction and fantasy fields within that most prestigious of movie awards ceremonies. But given the controversy surrounding the show’s perceived undercurrent of sexism and other ugly mentalities, primarily attributed to the show’s host, I decided to steer clear.

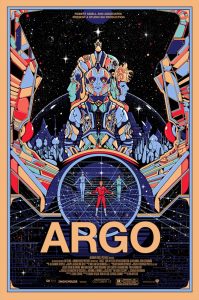

Instead, I wanted to take a look at this year’s Best Picture winner, Argo, directed by and starring Ben Affleck.

The film follows the declassified, mostly-true story of CIA operative Tony Mendez, who received the Intelligence Star when he rescued six American embassy workers from Tehran in 1980 by flying into the city under the pretense of filming a science-fantasy adventure film, called Argo in the movie, based on Roger Zelazny’s novel Lord of Light.

Now, I’m no history scholar; I am not ashamed to admit that — having been born and raised in the nineties — I had never heard of the Iran Hostage Crisis prior to the release of this movie. And I can’t be the only member of my generation to admit it, which is why it’s so important that these kinds of stories are being told today. Some have criticized the film for taking artistic liberties with the facts, while others have praised Affleck for his undeniable directorial chops. I, for one, find great value in its postmodern perspective on metatheatricality as a tool for not only examining historical events, but also for shaping them.

At the beautiful but chaotic start of Argo, we glimpse a period of civil unrest, in which the peoples of Iran are protesting against the militaristic American presence there, and likely also their government’s perversion of Western modernity, among other causes for discontent. It appears a violent, momentous time — but what does it all mean? What do the Iranian dissenters hope to achieve by forcibly taking fifty-two American diplomats hostage?

We see Chris Terrio’s script, which also took home the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, gesture at answers to these kinds of questions; most brilliantly, I’d argue, in the film’s opening narration, which utilizes colored storyboards drawn in the style of Jack Kirby’s original concept work for Lord of Light.

But it is the film’s use of popular science fiction, and the real-life theatricality by which the CIA managed to infiltrate Tehran, that illuminate the power of storytelling as a means of understanding — and, in many cases, simplifying — the complex truths of human conflict.

Mendez (Affleck) first begins to see the possibilities for his bold scheme when he visits his son, who is at home watching Battle for the Planet of the Apes on television. He goes to makeup specialist John Chambers (John Goodman), who agrees to help with the operation. When Mendez asks him what he’s been working on, Chambers replies, “Monster movie. Target audience will hate it.”

Mendez says, “Who’s the target audience?”

And Chambers tells him, “People with eyes.”

So begins the film’s outside assessment of what was, in 1980 and even well before then, the greater public’s regard for science fiction films. Aside from mega-hits like Star Wars in ’77 and the legendary Apes films before it, or Kubrick’s unsurpassable 2001: A Space Odyssey, SF in the realm of cinema had largely been ghettoized into infamy; a film like the fictional Argo would have existed on the same plane of art as Forbidden Planet, or the Godzilla flicks.

One of the diplomats in hiding, upon seeing the Argo script for the first time at the Canadian embassy, remarks, “It’s the theater of the absurd.”

And just before we’re shown droves of off-duty Cylons, C-3PO lookalikes, Chewbacca siblings, and a villainous, bearded lord who looks suspiciously like Flash Gordon’s nemesis Ming, Alan Arkin’s composite character, Lester Siegel, explains that a genre or art form is defined largely by whatever images outsiders choose to associate with it: “If it’s got horses in it,” he explains, “it’s a Western.”

Terrio’s script, in other words, seems at first to have a low opinion of the science fiction field.

Yet . . . we watch as Affleck ingeniously interweaves scenes of turmoil and violence with would-be actors practicing their lines; juxtapositions of Iran’s magnificent architecture with the globalization of Western corporate enterprises, like Kentucky Fried Chicken; and glimpses of a dead man who has been hanged from a crane on a public street corner, and of military transport trucks carrying armed mercenaries as Mendez rides into the city by taxicab.

Amid what seems like total pandemonium, we are given a sense of order through the shared act of rehearsed dialogues, monologues, and black-and-white, good-versus-evil exposition.

This fictional drama keeps our heroes safe, to a degree, from the horrors of this-worldly conflict — not through escapism, as science fiction is often reputed to do, but rather through preparedness and the classic spy-thriller device of theatrical disguise. We move from an escalating hostage situation to the CIA declaring, “The United States government has just sanctioned your science fiction movie,” to Siegel (Arkin) lamenting the state of the nation: “John Wayne’s in the ground six months, this is what’s left of America.”

Meanwhile, Mendez counters this memorable bit of commentary with the later counterargument that, “I think my story’s the only thing between you and a gun to your head.” Not speaking to Siegel, in this case, but the dialogue nevertheless exists in the film’s metadramatic subtext.

One detail about the film that struck me as supremely important is when one of the characters, probably Arkin’s, explains the significance of the title Argo as being the name of the starship in the space opera film, the vessel that carries its heroes to their ultimate destination.

Another character insists that it’s named after the ship of the same name in Greek mythology, which was adapted into Ray Harryhausen’s legendary visual-effects spectacular Jason and the Argonauts (’63), which is a close pop-cultural cousin to the kinds of films John Chambers was making in the seventies and eighties.

For all its historical significance, which cannot be overstated, it’s hard not to view Argo as a treatise on the grand, mythic power of science-fiction storytelling — the kind of campy, adventure-heavy epics that dominated the big screen throughout the twentieth century, culminating with Lucas’s groundbreaking Star Wars in 1977. Films like the one Mendez claimed to be working on during the Iran Hostage Crisis reflected on the sins of the long century’s many wars before ushering in a new, if all too brief, era of innocence in America.

Alex Kane is an author, blogger, and critic whose work has appeared in Futuredaze: An Anthology of YA Science Fiction, Digital Science Fiction, and Foundation, among other places. He lives in the small college town of Monmouth, Illinois, where he earned a B.A. in English, and was recently named a finalist in the international Writers of the Future contest. Visit him online at alexkanefiction.com.