What is alternate history?

Not as easy question to answer. Historians have been speculating on “points of divergence” since classical times. The Roman historian Livy wrote the first “counterfactual” when he speculated on what would happen if Alexander the Great turned west in 323 BC. Like a true nationalist, he believed Rome would have easily defeated him.

Not as easy question to answer. Historians have been speculating on “points of divergence” since classical times. The Roman historian Livy wrote the first “counterfactual” when he speculated on what would happen if Alexander the Great turned west in 323 BC. Like a true nationalist, he believed Rome would have easily defeated him.

Recently alternate history has begun to find its place in fiction. What began as half formed settings in the 18th century grew into a genre covering books, games, comics, films, television and plays.

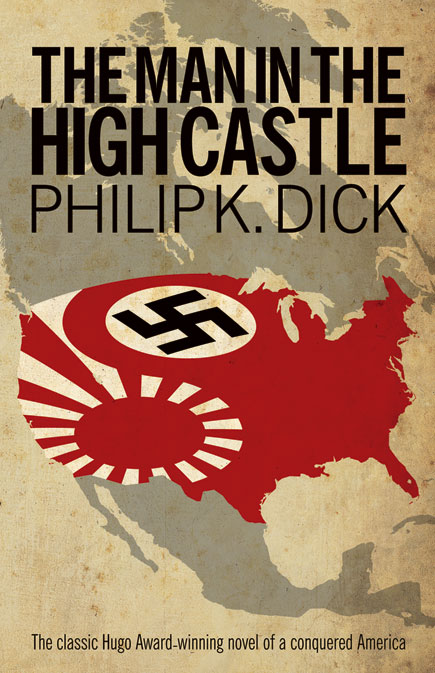

At first the genre remained firmly in the realm of pulp science fiction. A writer needed time travel and parallel universes if he wanted to present an alternate history. Things changed in 1962 with The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick. Although not the first alternate history to eschew “alien space bats”, it became the first such novel to get mainstream attention.

Afterwards, a new crop of SF writers with backgrounds in history arose in the 1980s. These writers took a sideshow of SF and changed it drastically. Although they did use such familiar SF plot devices (i.e. alien invasion) many of their works resembled historical fiction, only this time fictional characters and historical VIPs interacted in worlds where the Americans lost the Revolution or the Confederacy won the Civil War.

Their fans (and detractors) ran with it and gave the genre definition. The movement attracted more authors who brought new ideas. Some specialized in SF, but others (i.e. Michael Chabon and Philip Roth) came from literary fiction and found themselves attracted to the chance to write with less restrictions without sullying themselves by writing (gasp) “sci-fi”. Or as Ian R. Macleod told me: “Changing history seemed to me to be a way of turning a key into a strange and wonderful world, whilst leaving the door open to the characterisation, atmosphere and detail that you more often find in mainstream fiction.”

Yet the question remains: what is alternate history? Even during the Sidewise Awards for Alternate History ceremony at the last WorldCon in Chicago, the debate remains unsettled. Even the judges, those dedicated to choosing the best works of alternate history, disagreed about what can be called alternate history. Robert B. Schmunk has done an amazing job with Uchronia, the online database of alternate history literature, but not everyone is in agreement with Schmunk. The volunteer editors over at Wikipedia have listed S.M. Stirling’s Emberverse series as being alternate history, while Uchronia says the series “is either not allohistorical or is ‘border line’.”

So we cannot rely on an expert to tell us what is and what is not alternate history, but don’t get discouraged. Sidewise judge Steven H Silver came with perhaps the best formula to use for determining if an alternate history exists:

1) A point of divergence from history prior to the time at which the author is writing.

2) A change that would alter history as it is known.

3) An examination of the ramifications of that change.

This formula can help you better understand what you’re reading. For example, let us take a look at the first requirement. This pretty much removes historical fiction from the umbrella of alternate history. Fictional characters and places will not enough to classify the work as alternate history. You need an actual change to history.

The second half of the first requirement (time at which the author is writing) also removes retro-SF (SF set in a future at the time of publication, but now obsolete) from the equation. For example, I don’t think Stanley Kubrick and Sir Arthur C. Clarke intended to create an alternate history when they produced the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, yet people continue to list it and other retro-SF as alternate history as if it’s some catch all for out of date SF.

This issue has always been a major source of contention with me. Attempts to differentiate retro-SF from alternate history have led to some of the most irritating conversations I have ever had with SF fans. I often get the feeling my opponents haven’t actually read many real alternate histories, but know the genre exists. Lacking any real understanding they remind me of transvestite Eric Cartman screaming “Whateva! I do what I want!” Considering the numerous SF works about to become obsolete, these arguments will never go away.

The second requirement deletes the conspiracy theories and secret histories, or as I call them “the bane of real historians”. Don’t get me wrong, conspiracies and secret histories can make exciting fiction, if done right. They become a problem when you run into people who truly believe in some of this crap and attempt to label it as alternate history. It doesn’t help matters when the term “alternative history” describes these fringe theories along with the SF-oriented alternate history. Strangely I don’t have much contention with these misguided folk, but I have lost count on the number of books I have refused to review for my blog because they failed this requirement.

Finally, the third requirement informs us how idle speculation by a historian on how a Greek warlord would fare against a young Italian city-state becomes a work of alternate history. Something becomes an alternate history if it tells a story in an impossible, yet fascinating, setting. Without characters living the drama we call life, it cannot be alternate history.

So if you ever want to take a trip into the multiverse, I can recommend a few good books.

1 Comment