“I wish somebody’d tell me,

Tell me if you can

I want somebody to tell me

What is the soul of a man.”

–Blind Willy Johnson

“As he dropped the last grisly fragment of the dismembered and mutilated body into the small vat of nitric acid that was to devour every trace of the horrid evidence which might easily send him to the gallows, the man sank weakly into a chair and throwing his body forward upon his great, teak desk buried his face in his arms, breaking into dry, moaning sobs.”

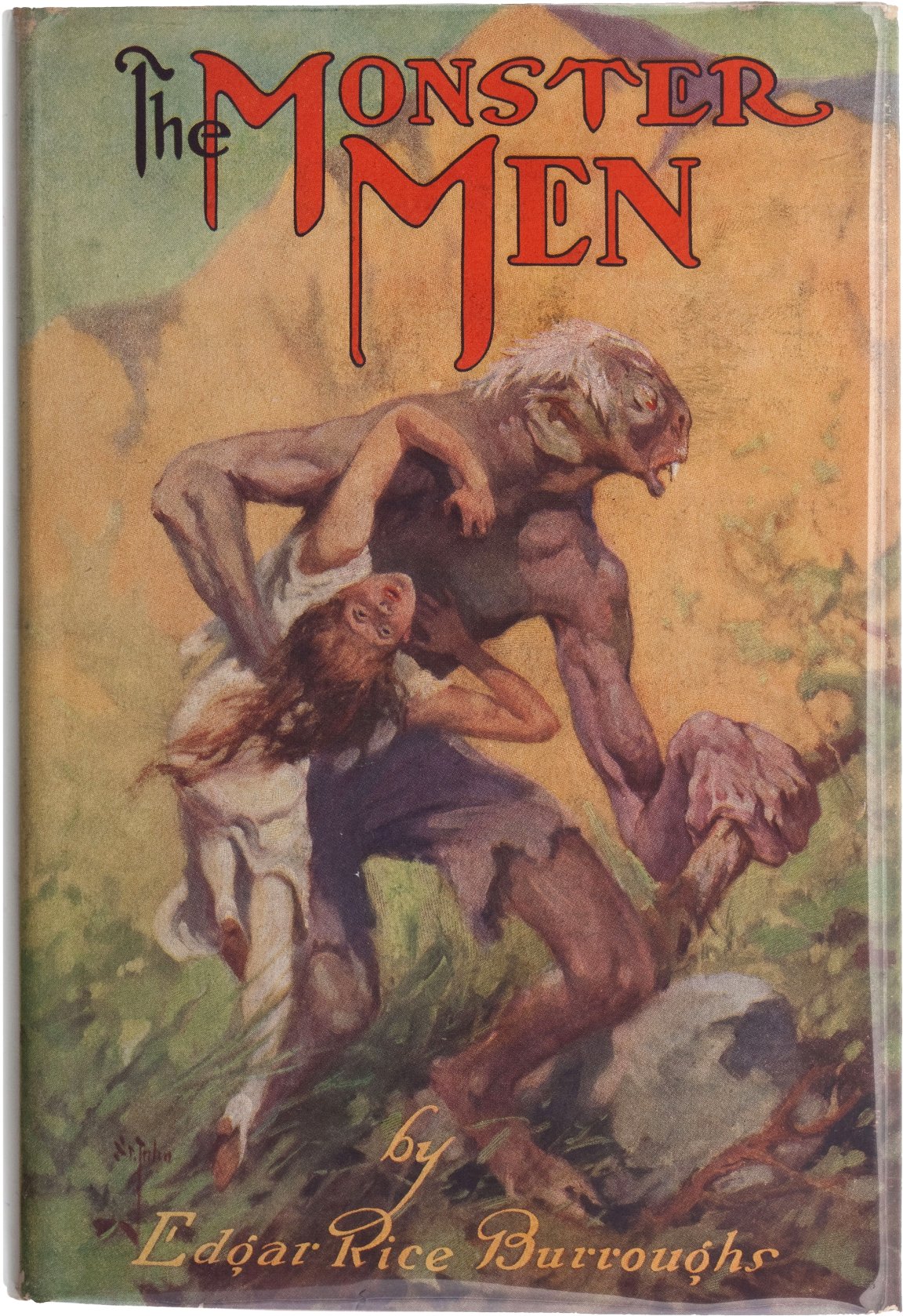

With these 66 words, Edgar Rice Burroughs began what is, in my opinion, one of the strangest, most fascinating stories he would ever write. First published in 1913 by All Story magazine under the title “A Man Without a Soul,” and later as a novel by McClurg in 1929, The Monster Men, is not only a wild and unusual tale, it’s one in which Burroughs, known mostly as a writer of escapist fiction, tackles a pretty heavy, one almost might say metaphysical, theme. In this work Burroughs asks the same thing that Blind Willy Johnson asked in the song quoted above. “What is the soul of a man?”

It’s a question that authors from Plato to Proust, from Kierkegaard to Kerouac, have pondered. What is it that separates man from the animals? Is there really such a thing as a soul, and how do you define it?

An editor might turn this story down if it were submitted today just on the basis of the long, one-line opening paragraph. It would be labeled a run-on sentence and the manuscript would have been stamped: REJECT. But take a closer look. The following words appear in that line: “grisly,” “dismembered,” “mutilated,” “vat of nitric acid,” and a man “breaking into dry, moaning sobs.” The sentence may be long and unwieldy but is it possible at this point to put the story down and not want to read further? As many have pointed out before, Burroughs was no stylist, but he knew how to tell a story. In fact, I’d venture to say for its ability to hook the reader, this may be one of the best opening lines of a novel since “Call Me Ishmael.”

In the opening chapter,” Burroughs presents us with Professor Arthur Maxon of Cornell University, an assistant professor in one of the departments of natural sciences. Always keenly interest in biology, Burroughs tells us, he had undertaken a series of daring experiments which had carried him so far in advance of the biologists of his day that he had actually reproduced life by “chemical means.” The only problem was that the result of the experiment was, shall we say, less than perfect? In the very first scene we find the professor having to get rid of a “grotesque and misshapen” corpse that was apparently a human being, but was in reality the remains of a “chemically produced counterfeit” created in his lab.

Next we meet the professor’s young and pretty daughter, Virginia Maxon. Here Burroughs presents a vivid contrast. Inside the lab, haggard, nerve-wracked, grey-haired Professor Maxon, disposes of the evidence, while on the other side of the laboratory door, the innocent, young girl, urges her “Daddy” to get out of the lab for some air and food, after being locked inside for three days. It’s at this point the professor knows he needs to get away for a while, if not to protect what’s left of his sanity, then at least to avoid harassment by the police.

We then find the professor and daughter on a long sea-voyage to the East Indies. You would think the cruise would have done Professor Maxon some good, but in reality, he’s been thinking that, while it would be unwise to conduct future experiments in Ithaca, he might be able to work undisturbed somewhere in the jungles of one of the islands. They go to Singapore, and there the professor and Virginia meet a Dr. von Horn, who becomes Maxon’s assistant. Von Horn is a less than scrupulous fellow with plans of his own and whose eyes light up every time he sees Virginia.

With von Horn’s help, the professor sets up a compound on one of the lesser Pamarung islands off the coast of Borneo. The professor gets to work, and  meanwhile we are introduced to a band of Malayan pirates, led by the ruthless Rajah Muda Saffir. At first he just wants money but, like von Horn, once he sees Virginia he has other ideas.

meanwhile we are introduced to a band of Malayan pirates, led by the ruthless Rajah Muda Saffir. At first he just wants money but, like von Horn, once he sees Virginia he has other ideas.

All this in Chapter One, which is entitled “The Rift,” so named because by the end of the chapter Virginia feels a cold distance growing between her and her father. If she had learned what he has in mind for her future, perhaps Burroughs would have called the chapter “Freakout!”

During the rest of the book, the professor creates 12 “humans” but like the one back in Ithaca, they’re pretty messed up. Hideous caricatures, in fact. In the meantime, von Horn has asked the professor if he can have his daughter’s hand in marriage. The professor becomes distraught, saying that it can never be. She should have only the best husband that science can create. He wants her to marry the perfect man, which he expects to someday create right there in his lab.

Maxon finally creates No. 13, and he seems perfect in every way. Then suddenly No. 1, the most hideous of the failed experiments, escapes from the lab and kidnaps Virginia, carrying her off into the jungle. No. 13 goes to her rescue. There are about a hundred miles of plot that unravel during the rest of the story, with No. 13 and Virginia battling not only No. 1, but the 11 other failed experiments, the Malay pirates, orangutans, and of course Dr. von Horn who wants the girl and the wealth he suspects Dr. Maxon possesses.

No. 13 is very Tarzan-like as he moves through the Pamarung jungles rescuing Virginia from her various perils. He’s the quintessential Burroughs hero— pure of heart, unspoiled by civilization. I’d call him a child of nature, except he was supposedly created in a vat of chemicals. But anyway, they fall in love with each other. And here’s where THE BIG QUESTION enters the story. If he is only the result of chemicals mixed in a coffin-shaped vat, is he really human? Even more to the point, does he have a soul? Is he fit to live in a world, where, supposedly, all men have souls?

After pages of scenes where No. 13 witnesses the behavior of men behaving more like beasts than men, there’s an introspective passage in the book where No. 13 contemplates the matter. He has asked the professor, and von Horn what a soul is but they couldn’t tell him.

“None of them knows,” No. 13 says. “I am wiser than all the rest, for I have learned what a soul is. Eyes cannot see it—fingers cannot feel it, but he who possesses it knows that it is there, for it fill his whole breast with a great, wonderful love and worship for something infinitely finer than man’s dull senses can gauge—something that guides him into paths far above the plain of soulless beasts and bestial man.”

It is his love for Virginia that convinces him he knows what a soul is. Ask yourself. Could Melville or even Faulkner come up with a better answer?

The book, unfortunately has a cop-out ending. I won’t reveal it here, because I don’t want to deter anyone from reading it. I suspect Burroughs must have been pressured by an editor to alter the finish because the correct ending would have been too controversial for its time. Still the contrived finish does not spoil what is otherwise a completely fascinating and thoroughly engrossing novel. It has all the trademark Burroughs touches in addition to the unusual, deeper, philosophical element. It is well worth reading.

The good news is that The Monster Men is now in public domain and is available for free Kindle download.

Incidentally, The Monster Men inspired me to write a short story based on the same idea. “The Man Who Had No Soul,” is one of the Mordecai Slate monster hunter stories. I changed the setting to Sonora, Mexico, in the 1880s. The story asks the same question Burroughs asked. I wrote an ending that I imagined he might have originally intended. It was published in Science Fiction Trails magazine. That particular issue is out of print but a Kindle version is available. The story won sixth place in the Preditors and Editors poll for best science fiction/fantasy short story of 2011.

“The Man Who Had No Soul” on Kindle is available on Amazon.com at:

John M. Whalen is the author of Vampire Siege at Rio Muerto, a horror western novel published by Flying W Press. His science fiction, sword and sorcery and horror short stories have appeared in numerous publications and anthologies.