A few weeks ago I wrote a blog about early influences that sparked my interest in science fiction. I was home from school a lot in the fourth grade, mostly asthma related, and my mom came home one day with a Tom Swift Jr. book. I had no idea where she got it. There weren’t any bookstores in 1959 such as we know them today (except for the major cities back east–New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, et. al.) I hadn’t yet graduated to reading comics, though I knew about Superman and Batman well enough.

The book she got was the first in the series, Tom Swift and His Flying Lab. Its cover showed a smiling blond kid (who looked like my best friend, Mike Stively, across the alley, but that didn’t bother me). I was more interested in the Flying Lab: a giant jet, the size of today’s 767s, that could take off vertically and had a small hanger in its undercarriage from which planes could take off and land. Is that cool or what?

Tom Swift Jr. was the son of Tom Swift, a boy inventor in the early 20th century who had adventures with his Motorcycle, his Submarine Boat, his Electric Rifle. There were 100 Tom Swift adventures, all published in book-form from 1910 to 1940. Since the Stratemeyer Syndicate owned the name, they launched Tom Swift Jr. in 1954. What I liked about the Tom Swift Jr. books was that his inventions seemed actually inventive. True he had a Rocket Ship and an Outpost in Space (a space station), but he also had a clever Diving Seacopter which could hover in air and split in two even. He also had an Electronic Retroscope that could read ancient hieroglyphics and a Spectromarine Selector that could remove elements from sea water and create new matter. He had political enemies called the Brungarians.

Tom Swift Jr. was the son of Tom Swift, a boy inventor in the early 20th century who had adventures with his Motorcycle, his Submarine Boat, his Electric Rifle. There were 100 Tom Swift adventures, all published in book-form from 1910 to 1940. Since the Stratemeyer Syndicate owned the name, they launched Tom Swift Jr. in 1954. What I liked about the Tom Swift Jr. books was that his inventions seemed actually inventive. True he had a Rocket Ship and an Outpost in Space (a space station), but he also had a clever Diving Seacopter which could hover in air and split in two even. He also had an Electronic Retroscope that could read ancient hieroglyphics and a Spectromarine Selector that could remove elements from sea water and create new matter. He had political enemies called the Brungarians.

These stories, though, were pure science fiction. Even in the first, the Swifts (for Tom’s father is present throughout the series), establish contact with aliens from Planet X in space through mysterious glyphs carved in a meteorite. There was a lot of space travel in a craft powered by his repeletrons: devices that could push against gravity (which also figured in the novel Tom Swift and His Deep-Sea Hydrodome). In the last novel, Tom Swift and The Galaxy Ghosts, he finally leaves the solar system.

There was no order to the Tom Swift Jr. titles. You could read them in any order, which I did. I discovered that a department store in downtown Phoenix had a small bookstore (more like a nook you’d find off in a corner of Penny’s or Sears) and found a couple there. They would often be side-by-side with the Winston Science Fiction books which were more expensive. I found more Tom Swift Jr. books in a hobby store about a mile away and my mom always let me walk there when I had the money from my allowance. (Like today, I spend most of my discretionary income on books, pulp magazines, and other science fiction-related items.)

There was no order to the Tom Swift Jr. titles. You could read them in any order, which I did. I discovered that a department store in downtown Phoenix had a small bookstore (more like a nook you’d find off in a corner of Penny’s or Sears) and found a couple there. They would often be side-by-side with the Winston Science Fiction books which were more expensive. I found more Tom Swift Jr. books in a hobby store about a mile away and my mom always let me walk there when I had the money from my allowance. (Like today, I spend most of my discretionary income on books, pulp magazines, and other science fiction-related items.)

These books, when I was nine, were just my speed. I dove into the Winston books later, and after that I read The Time Machine and the Robot stories of Isaac Asimov. I was about eleven by then and I was off. But I’d say that right now, the Tom Swift Jr. books were the most imaginative and the most influential. My mom told me to pay attention to how each chapter was a cliff-hanger and how overloaded they were with (what later came to be called) Tom Swifties. (“That’s the last time I put my hand in a lion’s mouth,” the lion-tamer said off-handedly.)

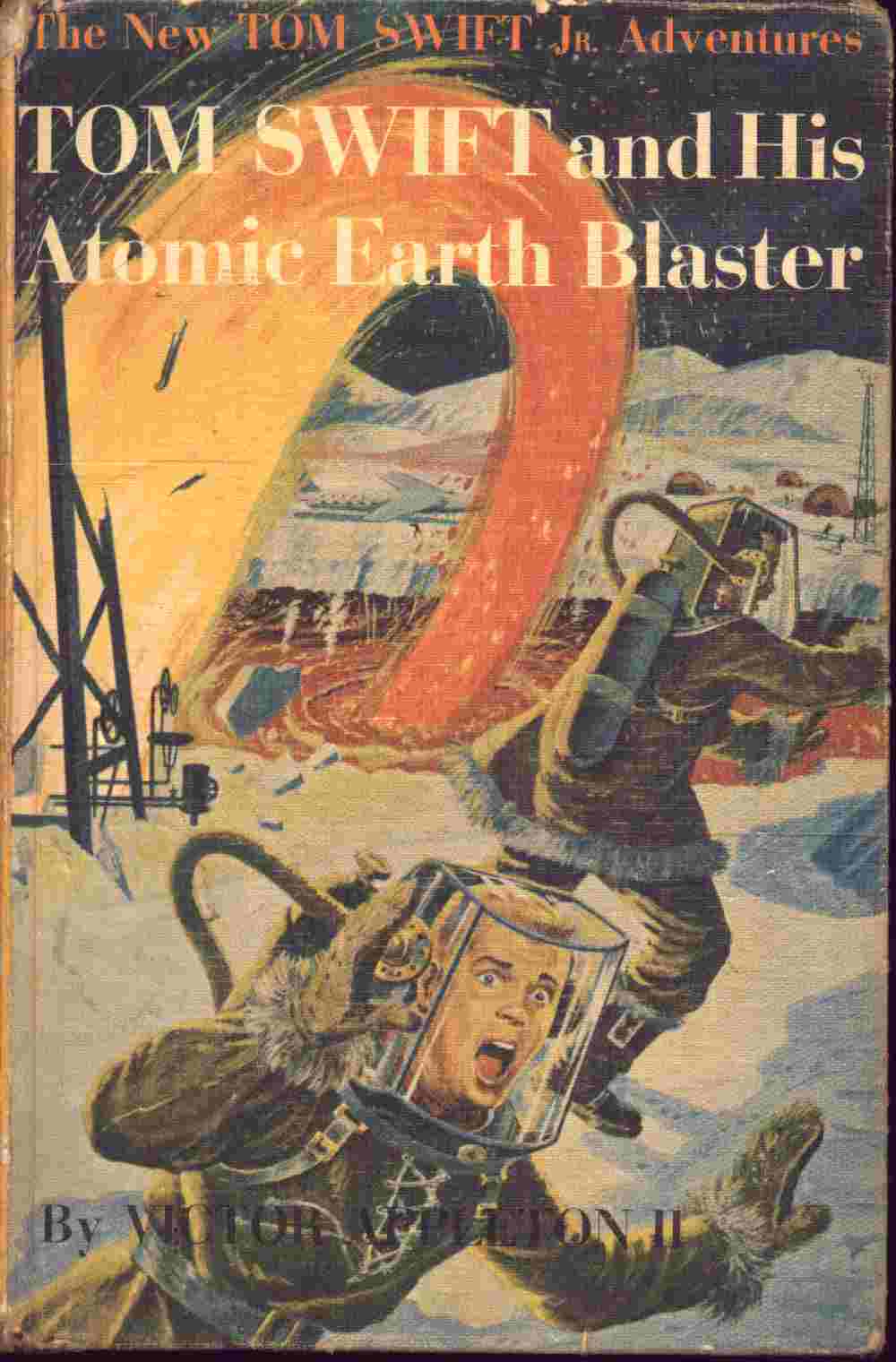

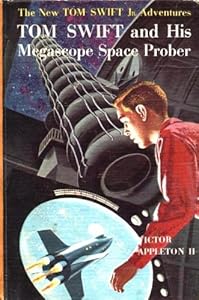

The Tom Swift Jr. books had great, evocative covers, quite pulp-like, and were quick reads. I have them all now–though I’ve yet to read Tom Swift and his Polar Ray Dynasphere and Tom Swift and the Mystery Comet.

The Tom Swift Jr. books had great, evocative covers, quite pulp-like, and were quick reads. I have them all now–though I’ve yet to read Tom Swift and his Polar Ray Dynasphere and Tom Swift and the Mystery Comet.

Nowadays kids have comics, superhero movies (and cartoons), and video games. I have no idea what sparks their imagination. But there’s something to be said about opening a book with a title like Tom Swift in the Caves of Nuclear Fire and wondering what sort of trouble had Tom gotten to himself this time?

–Paul Cook

Another interesting post. Thank you, Mr. Cook.