Intro

In the imagination, future and past fold over and into each other to inform our perception of the present. The Nasca culture that disappeared in the sixth century could very well look like a future post-apocalyptic society trying to survive in a future desert. A shamanic world vision could be seen as a return to ancient earth-honoring mystical traditions or as a result of extraterrestrial visits as imagined by Erich von Däniken. Yet, in the end, doesn’t every story somehow come back to our human struggles and how we navigate our relationships with other beings, including the planet that we live on? What is a heroine, if not one who answers the call to step into a destiny larger than herself, despite danger, fear, and self-doubt, because it is the right thing to do?

Setting

The desert coast of South America is veined with rivers that carry fresh water from the inland Andes mountains westward into the Pacific Ocean. For almost a millennium, the Nasca people flourished in the narrow coastal valleys of what is now southern Peru by tapping deep underground waters and engineering tunnels and canals to feed their farmlands. The Nasca also used the arid plains as a giant canvas to create art and ritual in the vast empty landscapes. Their adobe ceremonial temples of Cahuachi rivaled the Egyptian pyramids, and they produced textiles and ceramics still enviable today. The Nasca overcame drought after drought, earthquake after earthquake, ever resilient and ever resourceful, until the end of the sixth century, when their world began to come apart. Patya’s story begins in the midst of the worst drought the Nasca have ever faced.

Chapter 1: Loss

Late sixth century, Nasca Valley, Atacama Desert, western coast of South America

Even from here, I can see Achiq striding up our valley. The torches cast shadows off his staff, with its feathers and foxtails swaying. Light glistens across his golden mask as drums begin to echo up and down the valley, letting everyone know the priests are coming. Coming to claim my grandmother’s head.

Leaving the outside lamps dark, I slip back into the house and place an extra lamp next to my mother. “They are in the valley,” I say. She doesn’t look up, just continues preparing my grandmother, my paya Kuyllay, for burial. She nods to the basket of bracelets.

I pick out Kuyllay’s favorites and arrange them on her arm. I linger over the orca tattoo on her wrist. It’s identical to mine except that Kuyllay’s orca is as dry and lifeless as our riverbeds, while mine glistens with sweat and quivers with anger. The shaking travels to my lips and unclenches my jaw. “How can you let them do this?” I blurt out. “She belongs here!”

Mother still says nothing.

“Kuyllay died last night,” I remind her. “It’s a full day’s walk to the temple, yet their runner was here before midday. How did they find out so fast?”

Mother brushes a line of red cinnabar powder across Kuyllay’s forehead. When she finally speaks, all she says is, “I don’t know, Patya. I don’t know.”

The drums begin a slow dirge. Each beat deepens the hole in my heart. Kuyllay is gone. Kuyllay is gone. Kuyllay is gone. The great heart at the center of my days is gone. I have lost the hands that healed me when I was hurt, fixed me when I was broken, soothed me when I was sad. My teacher has left me before I have learned all she had to teach. My Kuyllay, my paya, more mother to me than Keyka who bore me. It was Kuyllay who marked me from birth, who forbade them from binding my head. Who promised I would be glad of it one day. But that day has not come, and Kuyllay is gone.

“We haven’t much time,” my mother says, her voice strangely vacant.

I don’t like her eerie calm. I want to shake her. Wake her. Make her see.

“Our ancestor Tuku Warmi’s umanqa has been with our family for more generations than we can count,” I say, pointing to the altar behind her. Smoke rises from a bowl there, filling the room with the heavy, otherworldly sweetness of wanqor wood. The tattoos on Tuku Warmi’s leathered skin are still vivid. Her long hair coils around her head, propping it up as if to watch us. I don’t want to think about how she became an umanqa, about how Kuyllay’s head, too, will become an umanqa. How they will remove Kuyllay’s skin to clean the skull and how they will pull it tight again over the empty bone and stuff in bits of cotton to round out her cheeks. I flinch at the thought of the long thorns piercing her eyelids and mouth to hold them shut. I have always revered Tuku Warmi’s umanqa and thought her beautiful, but I never knew her living, breathing face. It is another thing to see my beloved paya now and know what they plan to do. I turn back to my mother.

“If Paya Kuyllay’s head is to become an umanqa, it should stay here with her family, not the priests!” I continue. “Do you really believe it is the will of the gods that her head go to the temple?”

Mother won’t look at me. I can’t stop myself. “It’s more like the will of Achiq!”

Her lips tighten. She smooths another red streak across each of Kuyllay’s cheeks, then finally looks up, her face blank, her voice full of sadness. “We’ve already talked about this, Patya. Kuyllay does not belong to us alone. She may be my mother, she may be grandmother to you and your brothers, but she is beloved all along our coast and far beyond the mountains. If she can still help the priests do medicine work even in death, she would want that.” She sighs as she arranges Kuyllay’s hair. “I just never thought this time would come so soon.”

“And I did not think the priests would come so soon. Achiq,” I snap back, spitting his name out like the poison he is. “You know he feeds on power. Now he wants hers too.”

“Patya!” Mother holds up her hand. “Enough! Do not say things that the winds could carry to the wrong ears. It cannot be changed.”

I glare at her. Why does she refuse to see evil that is so obvious to me? She locks eyes with me, but she has blocked me out. The silence between us fills with the ominous pulse of drums, ever closer. They throb inside me. Kuyllay is gone. Kuyllay is gone. Kuyllay is gone.

Mother gentles her voice. “This has always been a possibility, Patya, a way to bring hope to our people after her death. Like great healers before her, like our ancestor Tuku Warmi. She accepted the will of the elders, as you must. For the good of our people, Patya. No questions, no complaint. We must pray that Kuyllay’s voice from the beyond can sing our rivers back to us.”

I bow my head, but I’m not giving up. Yes, I will pray to bring the waters back, but I know Achiq is not the one who can do that, even with Kuyllay’s help. Yes, I will pray. If I can’t stop Achiq from taking Kuyllay’s head, then I will pray to find a way to get it back.

The drums ebb and flow as the procession zigzags its way up the steep hill to our home. Even in the blur of cleansings and floral waters, incense, and prayers, I haven’t stopped searching for an explanation. How could she die with no warning? How could her spirit leave so suddenly? My mind can’t stop hunting for clues—while I rub oils into Kuyllay’s skin, braid her hair, choose the ceremonial cloths, gather offerings for her tomb. I review our morning together collecting medicinal plants, Tachico tagging along, full of his usual mischief, and Chochi, the equally mischievous monkey, riding on his shoulder. The afternoon hanging herbs to dry. Patients stopping by for salves and tonics. The evening meal. The usual night routine.

Kuyllay was on her sleeping mat, me on the floor next to her, painting a pot, and Chochi was curled up between us. Kuyllay complimented each creature that took shape under my brush. Her voice grew soft as she drifted into sleep: “ . . . don’t forget the shape-shifter.” There was a late-night chill when I finally finished painting her favorite shape-shifter with Orca’s fins, Jaguar’s face, and Great Owl’s wings. I remember stepping out to greet the moon, full and glorious, before going back in to cover her with an extra blanket.

I remember the impossibly cold skin when I bent to kiss her cheek.

I don’t remember crying out, but that’s when Mother leapt to her side. Even Mother, trained by Kuyllay herself, could not bring back the breath that had left my paya’s body.

I begged her spirit to return. But the wind carried Kuyllay’s voice farther and farther away, until only echoes remained. Echoes of the lists she had drilled into my memory. Golden jaguar headdress, three bowls of purple maize, sandals for the rocky paths, knives to cut through haze . . . That’s when I realized that my paya Kuyllay had been preparing me for this since I was small.

She used to joke that preparing for the afterlife was like furnishing a new home. She made me guess what she wanted in her tomb and gave me a treat for each item I guessed right. Her tricks worked. My mind automatically ticked off the list. Two crocks of hearty chicha beer, three double-spouted jugs, a pot adorned with seabirds, a thick alpaca rug. She also wanted the usual llama to make her burdens easy to carry and a baby alpaca so wool would be ample. I remember the gleam in her eyes when I would recite, Two plump and tasty quwis, two black ones for divining, the platter with the monkey in a tree reclining . . . How could I forget that one? Kuyllay made me promise not to let anyone bury her pet monkey with her. “The platter will be enough reminder,” she said. “Chochi is meant to finish out his life here.” But I haven’t seen Chochi since last night.

Wind laps at the drape that covers the doorway. A gust of air slithers across my neck. Voices begin to mingle with the wind. My father and brothers are back—Otocco, bossy and impatient as usual, is directing Tachico where to put things. He’s the oldest and thinks the rest of us should jump at his command. Tachico doesn’t mind the way I do—he just loves to be included by his older brothers. It sounds like Ecco is soothing a nervous llama. Maybe it senses its imminent sacrifice. Ecco’s always been good with animals. And with people. He’s a couple of years older than me, but he doesn’t have Otocco’s mean streak.

I am reluctant to leave Kuyllay’s side, but I go to greet my father. He looks haggard as he lays his hand on my shoulder, gives me a reassuring squeeze, and then goes inside to talk to Mother. The lamps outside are lit now. All that much easier for the priests to find their way. I lean over the low wall that circles our terrace and corral. The procession is halfway up the hill. Tachico joins me, watching the flames of their torches dance with the shadows. “Are they really going to take her head?” he whispers.

I put my arm around my sweet little brother. Somehow, he makes it easier to breathe. “Come on,” I tell him, “let’s say goodbye before they get here.” Ecco joins us as we go back inside and kneel next to our grandmother. Her face is calm, as if she’s merely asleep.

“May you be at peace, Paya Kuyllay,” Ecco says softly. “May you visit us in our dreams and live in our hearts. May our footsteps on the earth feel the echoes of your passage before us, and wherever we walk, may we honor you by living your teachings and sharing your memory.”

“Let it be so,” I say.

Otocco is whispering with our parents in the corner. The only words I catch are “they shouldn’t watch.” And then drums are on top of us. Father goes out to meet the priests, but Mother stands next to our paya, straight and proud.

Achiq’s form fills the doorway completely. He overwhelms our house the moment he steps in, wearing his full regalia—a fox skull headdress adorned with an excess of foxtails, a cloak of fine furs, and three umanqas on his belt. With his arms spread wide and his staff bumping the roof, I have to squeeze against my paya to let him go by. As he parades past me, I recognize one of the umanqas on his belt—the head of the priest in charge before Achiq. The one who died mysteriously.

My father follows behind Achiq, then takes his place beside Mother. Otocco and Ecco bow and retreat outside to watch from the door. Otocco gestures for me to leave also, but I ignore him and pull Tachico close to me. The other priests stay outside, waiting to be summoned. Their torches light a circle within the low stone walls. Achiq’s voice booms, “As the solstice approaches and Tayta Inti pauses his journey through the sky, it is auspicious that our revered healer, Kuyllay, shall be honored in the custom of our ancient traditions. From the other side of death, she shall continue to serve the sacred, and to serve our people. We bear witness to this sacred ritual that consecrates the head of Kuyllay of Nasca, Clan of the Orca, Lineage of Paracas Medicine Women. Tonight her mortal flesh and bone shall be transformed into an everlasting umanqa.” He pauses for effect. Another priest enters with a tray that he places beneath Kuyllay’s neck. I almost don’t recognize the haggard face, but when I notice the sadness in his eyes, I realize it is Tikati, an old friend of Paya Kuyllay’s.

Achiq raises the ceremonial knife.

I can’t help myself. I lunge toward Achiq, but something yanks me backward out into the corral. Otocco has a hold of my arm. “Don’t be crazy,” he says into my ear. “You’ll get us all into trouble.” I shake him off and try to go back in, but he drags me to the end of the corral.

“You don’t care, do you?” I cry.

Otocco looks at me like I’m a kid having a tantrum. “You have to think about others, Patya. It’s not just about you.”

I hate it when he acts superior. How could he have any idea? He’s never spent time with Kuyllay the way I have. His life won’t be that different because she’s not here. He doesn’t mind the idea of Achiq using her umanqa to impress people. Might even like the status it gives him.

“It’s about keeping the peace,” he says. “And giving people hope.”

“Go ahead, tell yourself that,” I reply. Our parents might believe that, I want to say, but all you really care about is your reputation. I look to Ecco for support, but he disappoints me.

“He’s right, you know,” Ecco says.

Tachico is also regarding me somberly, his eyes glistening with tears. There is no sign of the impish little brother I’m used to. “You’re not the only one who loves her,” he says.

It’s like a punch in the stomach. Tachico, the one who always looks up to me, is looking at me like I’ve done something wrong. I realize I haven’t even noticed him since last night. The boy has only seen seven sun cycles, but today he seems more grown-up than me with my fifteen. He’s in as much pain as I am, but I am the one who is sinking into a dark cloud. It swallows me. I don’t want to see what they are doing. I don’t want to feel it.

It takes two days to get to the ancestral burial grounds of Muña. I do what I am told. Carry what I am told to carry. Recite the prayers. My body goes through the motions, but it’s all such a blur that I can’t even tell if I am crying. I don’t speak to anyone, not even faithful Tachico, who’s always beside me.

We fill the tomb with everything Kuyllay wanted and more, including the beautiful ceramic head jar that Ecco made for her mummy bundle. Another reminder that her head is now an umanqa in the hands of Achiq. People come from all over with offerings for Kuyllay’s tomb. The rest of my family is proud of all the honors given to Kuyllay. Not me. I can’t stand the way Achiq parades her umanqa around everywhere as if she had given him a special blessing. I can’t stand all his talk about making sacrifices so that the rains will come back. He wants blood.

I try to shut it all out, and look to the moon for comfort. But even Mama K’illa shrinks away from me, night by night, little by little, until her final sliver disappears, and I wrap myself in the tapestry of stars to wait for her return.

When we finally return to the familiar outline of Yuraq Orqo, I begin to feel present in my body again. In the shadow of that mountain, I am home. The razor’s edge of sadness begins to soften and merge into the haunting, mournful drumbeat that pulses in my soul.

Chapter 2: Pachamama Speaks

Almost three moons have passed since I last worked in the drying shed. I haven’t been back here since bringing the last batch of plants I collected with Paya Kuyllay. The shed is bright with afternoon sun. Flowers and vines hang everywhere—dry, withered, and waiting to be stored. My nose wrinkles as I pull down a batch of pungent leaves and stuff them into a clay jar. I fill another pot with clusters of muña, savoring the earthy scent even though it makes my longing worse. I find myself wondering if the burial grounds were named Muña because the plant once grew there in abundance, or because of its properties—useful for preserving things, helpful for breathing in thin mountain air, good for digestive problems. So useful that I left several pouchfuls in Kuyllay’s burial chamber. She will not lack remedies in the afterlife.

Ay, my beloved paya! How can she be stuck in a desert tomb three valleys away, wrapped in radiant layers of ceremonial cloth, while her umanqa is hostage to fanatics in the temple? I must find a way to bring her home, I tell myself, repeating it vigorously as I wrestle a thick root apart and break it roughly into pieces.

Mother’s voice interrupts from the door. “Patya, don’t bruise them.”

Mother is busier than ever now that Kuyllay is gone. More patients. Always in a hurry. She deposits a basket of herbs beside me and places a hand on my shoulder. “Be careful not to let your feelings bleed into the plants,” she says. “You don’t want to damage their potency.” As she leaves, she glances back. “I’ll send Tachico up to help.”

I hide my smile. She knows I would rather be painting pots than filling them with herbs. I hate trying to keep up with the medicine plants, but at least Tachico will make it fun. Watching after my little brother and keeping him out of trouble is still my favorite chore. His company will be welcome in this dusty shed.

I am finishing with the fever bark when the ground begins to tremble. Herbs start swinging; ceramics clatter. I freeze, waiting to see if another tremor will follow. The floor shudders slightly, then stops. I let my breath out and continue working. I have gotten used to the earth’s stirrings and try not to worry unless it gets worse. Pachamama may be awakening, but it’s probably just a sleepy stretch.

My mother suddenly rushes in, her face flushed. She grabs me and tugs. “Get out!” Tachico is standing outside at a distance, pale and nervous, his wide eyes half hidden behind his disheveled hair. The herbs are still swaying.

“But Mother, it’s over.” I shrug her off to finish putting the last of the bark in its pot.

“If we are lucky!” she says.

“You used to tell us it was just Pachamama waking from a nap,” I protest as she tries to pull me out the door. “Or shaking her skirts. Remember?”

Once we are outside, she takes my shoulders and holds me, her eyes sharp and demanding as she looks into mine. “Sometimes it is. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be careful. When Pachamama shook those skirts once, they buried my brother. If a beam falls down, Patya, I don’t want you under it.” She cups my face in her hand. “Promise me you won’t wait next time.” Tachico is peering up from behind her, his worried face fixed on mine. “Promise me!” she demands.

“Yes, Mother,” I reply.

Tachico wraps himself around my legs in relief.

As we approach the house, we hear canal-keepers climbing the hill, with urgency in their voices as they call out for our father, “Yakuwayri, Water-Guardian!” Father stands tall and calm, with Otocco beside him. They welcome one after another and listen to their reports. Old channels, already repaired many times, have broken open again. With water so scarce, even the smallest leak can be devastating. The tremor had not been as benign as I thought.

Tachico lets go of my hand and runs to Father. “Can I help, please? Can I help?”

Father nods at me as he pats Tachico’s head and then pushes him back toward me. I recognize the look. Keep Tachico from getting underfoot; we have work to do.

So Tachico and I climb the rocky slope behind our house until we find our favorite boulder to sit on. We watch dusk fall as people continue to gather below. We’ve watched such scenes before. Tension fills the air—worry that a bigger quake might be coming. I distract Tachico by telling stories about Mama K’illa the Moon, how she fell in love with Tayta Inti the Sun, how the sky keeps them apart but they speak to each other through dreams, how I once witnessed the flash of their kiss during an eclipse. We sing songs to the moon until we are ready to slide our way back down the hill toward bed. Before we go in, Tachico announces, with all the confidence of his seven years, “I will ask Mama K’illa for a dream tonight. She will show me where to find more water.”

The next morning, Tachico wakes me up, all excited. “I dreamed about the old well near Uncle Weq’o’s farm!” he tells me. “I saw a snake go into the opening. It slithered in as dry as the desert, but it came back out all wet and muddy.”

“I remember that well. It stopped flowing before you were even born,” I say.

“I know! Father said an earthquake opened a crack underground that swallowed all its waters.”

“I was about your age then. I remember them digging for weeks and never finding another access.”

“Well, I think this tremor shifted things again.” Tachico smiles, eager to get going.

Tachico has a gift. He has found water before. Nothing big, but in times like these, even a trickle means a lot. Like last year, when the spring dried up by where the caravans usually camp. Tachico found a branch to his liking, made himself a divining rod, wandered around a bit, sort of trancelike, and then moved some rocks and found another spring! No one had suspected it was there just beneath the surface. I don’t know how he does it. It’s like the water calls him. But it’s unpredictable. Water has its own spirit and its own time, but when it does call him, it is usually around a full moon.

While the work groups go off to take care of repairs up the valley, Tachico and I gather our supplies and set out in the opposite direction, toward the lower valley. He is in great spirits, scampering down the hill with sure steps. We reach the dusty riverbed and then work our way down the valley. “Remember the old digging song?” he asks, but doesn’t wait for my answer. He just starts singing, “In the rocks below, in the hills above / seek cracks and veins / to find earth’s blood. / Some will close, some open wide. / The best of them / are deep inside.” He grins at me. “We just need to find the right crack.”

I laugh. “Some look for silver and gold; we look for cracks.”

“And we will surely find a good one!” he says, then stops and turns to me, suddenly serious. “Patya, you do know that water is more useful than silver or gold.”

“Of course, Tachico. Anyone who has ever been thirsty knows that very well.”

We have stopped right where we need to turn. We follow the scraggly line of guarango trees toward the valley walls that border the once-productive cotton field. Now the area is nothing but packed earth littered with rocks. Not only has the water disappeared, but the rich soil that once produced plentiful harvests was washed away in a huaico from the highlands. The deadly combination of flash flood, rocks, and mudslide swept away the harvest and left the field useless, but we still come here every year to gather guarango pods from the trees that survived.

The well here is one of the first puquios our ancestors engineered to reach the underground waters. Close to the steep hillside at the end of the field, the stone-lined path that spirals into the earth is narrower and steeper than most. I pick my way carefully, testing the ground with each step, but Tachico dances his way down, intoning a water song to the beat of his feet. He continues the song while he waits for me at the bottom. “Yakuta mañamuy, yakuta mañamuy, taquiricuspa mañamuy, taquiricuspa mañamuy.” Asking we come, asking for water, asking we sing, singing we ask. The words vibrate in the empty well.

When I get to the bottom, I add my own prayer to Pachamama. “Have mercy on our people, and our thirsty fields. You have seen us through hard times before, shown us the way to your waters, and once blessed us with abundant crops and generous game. Now these lands have grown so dry that the deer have gone, the guanaco are scarce, and even the fox cries for mercy. Please guide us, your children; show us the way—”

“Amen!” Tachico interjects, eager to get going.

“Let me finish.” I shush him and continue, “We ask permission for Tachico’s journey into your womb, we ask your blessing, that you may show him where to find your life-giving waters.”

He waits for my nod, then touches the wall of the puquio and says, “Amen. May it be so.”

I get the safety rope ready while Tachico peers into the tunnel opening. Suddenly, I am not so sure that this is such a good idea. I wish I felt as confident as he does. He waits impatiently for me to tie the rope around his waist, then climbs down the stone wall to the level of the tunnel. I stand at the end of the path, my feet level with the top of the tunnel, Tachico’s head level with my knees. I light a small torch from my coal pot and pass it to him. He ducks down and crawls into the opening. I let the rope out slowly, feeling more nervous with each length that unwinds. How did I ever agree to do this? Mother would be furious.

Tachico has no fear. He is short enough to walk upright through some of the bigger tunnels, thin enough to squeeze through narrow sections, and young enough to ignore the dangers. Each moment he is underground, my heart clenches a little more. I won’t feel right until he is out of there and back aboveground. But it isn’t just Tachico that worries me. I glance around to make sure we are still alone, but we are below ground level, so I can’t see the land around us. The poison darts hidden under my tunic give me some comfort, but I am still uneasy. I do not want anyone to take me by surprise, not ever again.

As the rope uncoils into the darkness of the tunnel, I watch a pair of birds peck at the ground nearby. At least that’s usually a good sign that the ground will not be shaking soon. After a bit, the rope goes slack. He has stopped advancing. I lean my head down and shout into the opening. My voice echoes back. “Tachico!” I tug at the line but get no response. I tug again. “Tachico!” Nothing. I take a deep breath. Try to tame my fear for Tachico so deep under the earth. Tame the worry for myself. I touch my darts, just to make sure they are there, and force myself to breathe the way Kuyllay taught me. I inhale the fear, taste it, and exhale it cleansed of its poison. I inhale the dark images that rise from the shadowed places of my mind. I let them rest in my breath, conjuring her presence, her compassion, her love, and exhale those images, knowing that no arms are holding me down now. It is only the shadow of memory. Shadows that cannot hurt me.

Something else tugs at my attention. I tell myself again to breathe. A garbled sound comes from deep within the earth. Another tug. My mind clears when I realize it is a triple tug on the rope—Tachico’s code for more line.

I yank back with a firm “no.” I do not want Tachico going any farther.

He tugs again, three quick, insistent tugs. A pause. Then three more. Reluctantly, I relent, let out a little more line, then wait. And worry some more. I give the rope another sharp tug. It jerks in reply, then goes slack. Thank the moon, he is on his way back! I tie a piece of red yarn to the rope to mark the distance and then begin reeling it in, thanking Pachamama for tolerating our intrusion, grateful that Tachico is coming closer with each loop around my forearm. “If we have offended you, please forgive us,” I pray, “and let the waters flow again.”

Tachico’s head emerges first, his dark eyes gleaming and toothy grin shining through the dirt on his face. “I know where it’s blocked!” I put the rope aside and lie on my stomach to reach down to take the torch from him. He passes it to me, then stretches his hand for me to help him climb back up.

Suddenly, the ground jolts. Just as I grab hold of Tachico’s hand, the lintel above the opening gives way. The air fills with dust. Terrified, I pull with all my strength. Rocks clatter and tumble. I lose sight of him but tighten my grip on his hand. I manage to get my other hand around his wrist. While the earth caves in around us, I pull hard and pray. Everything stops—breath, sound, time—as I struggle to keep my grip in the rubble. My arms tremble; my muscles strain in desperation. I summon a last burst of energy and twist myself backward, dragging his weight with me. In a sudden lurch, Tachico lands at my side.

Gasping for breath, my heart racing, I rub the dirt from my eyes and try to see Tachico through the dusty haze. The ground becomes still again. As the dust begins to settle, I can make out his scratched face and a muddy red stream flowing down his shoulder. “You’re bleeding!”

Tachico glances down, but he barely flinches. “Blood,” he says matter-of-factly, “a gift for Pachamama. I owe it to her. Don’t worry, I’m okay.”

Once we get back to the surface, I fuss at his wound. “You’ll survive,” I say, “but hold still so I can get the gravel out from under this flap of skin.” He winces, then lets me check the other side. “Oh, Tachico, look at the rest of you! You’ll be so purple tomorrow.” I am already dreading Mother’s reaction.

“It was worth it,” he says. “I told you there was something here!” He pats the ground. “I reached a bend blocked by rocks, but Patya, I could smell water. I just kept pulling the rocks away. Then I found it, a break in the earth! I could hear the water below. It’s deep, but I know we can get to it. Pachamama wants us to have it.”

I just stare at him, not sure whether to laugh or cry. I finally nod and pour some water from my pouch onto the ground with as much ceremony as I can muster. “Beloved Pachamama, thank you for your protection. We celebrate the water in your veins. May its abundance bless us.” I cup my palms together, blow my prayers into them, and then blow my thanks to the earth. Tachico repeats my motions with water from his own pouch and then drinks thirstily. We gather our things and start for home.

“Before the blockage, there was a horrible smell,” Tachico says. “Something rotting. I almost vomited . . . There were bones cracking under my knees.”

“I’m just glad it didn’t end up being your bones in there.”

“Stinky flesh falling apart . . .”

“Please, no more details.” I walk faster.

“Something oozing . . .” Tachico taunts.

“I’m not listening.”

“Bugs crawling . . .”

“Tachico, stop!”

By the time we get home, the sky is rolling pink across the hilltops. Our parents receive Tachico’s report solemnly. Mother glares at me, but I keep my eyes on the ground.

“Patya,” she starts, but I interrupt.

“I know it was dangerous. But Tachico—”

“Is seven years old,” she snaps.

“I’m sorry.”

Father places his hand on Mother’s shoulder. “Keyka, if the gods have honored our son by guiding him, we must be grateful. A few cuts and bruises are little to pay for such a gift. This is a good day. The canal upriver should hold up with our repairs, and Tachico has given us a new task. We will begin tomorrow and pray that we can reach the water he speaks of.”

I pray that Tachico is right.

While Mother tends to Tachico, I linger on the terrace, looking out over the valley. I used to sit here with Paya Kuyllay and listen to her stories. She liked to tell how our ancestors chose this place to build their home, above a fold of rock where the Aja River from the north meets the Uchumarca River from the east. “It is auspicious to live near such a place,” she would say, “a tinkuy where two energies merge. We are also high enough to be safe when heavy rains in the mountains send huaicos crashing through our valley.” I find it hard to imagine so much water ever passing through here again, though. Not even a minor flood has threatened since the last river walls were rebuilt.

When I would complain about having to carry water up the hill, Kuyllay would remind me that there was no view as beautiful as ours. From here, high above the riverbanks, we would watch Mama K’illa’s nightly journeys across the sky, watch her grow daily from a silver sliver to a bursting fullness, and watch her shrink again until she disappeared. Each morning we would welcome Tayta Inti’s golden rays as he rose from behind the white slopes of Yuraq Orqo. We measured our days by his travels across the sky, until he reached the sea and dove in, taking the light with him.

A plume of smoke rises from a house on the far hillside and a condor glides past like the Lord of Winds, spreading his wings to greet the night and disappearing over Yuraq Orqo. I long to be there, at the top. My solo pilgrimage to Yuraq Orqo was supposed to be on the solstice but was postponed after Kuyllay’s death. Now I will have to wait until after Ecco’s wedding. Kuyllay won’t be here to help prepare me, but I am impatient to complete the ritual, not just to take my place in our community but because Yuraq Orqo is more beloved to me than all those distant highland peaks. Next to those great Apus, our sacred mountain may be small, but she is a beautiful mystery surrounded by legends, the manifestation of a goddess. I love the way the sun turns her golden, the way the moon bathes her in silver, the way they are her companions as she is ours, constant and true. I can’t help but wonder about something, though . . . Kuyllay called Yuraq Orqo the Giver of Waters and told of how she showed compassion for our ancestors by sending them water when they suffered. Why does she not do so now?

“What are you thinking about?” Mother asks from behind me. She envelopes me in a hug, so she must have forgiven me for my adventure with Tachico. Her hands fold over mine. She sighs and says, “Your hands are long, like your grandmother’s.”

Mother never seems to tire of pointing that out. I don’t know why it bothers me now; it didn’t use to. Now it’s just another reminder that Kuyllay is gone. I pull away and turn on her, suddenly impatient and irritated. Heat rises to my cheeks. “It’s bad enough that Grandmother’s body is in Muña,” I say, “but how could you let them take her umanqa to Cahuachi? She belongs with us!”

Mother looks disturbed. “I thought we were past that,” she says. “The decision was made by the elders. I know you want it to be different, but what we want . . .”

“Is not always what we get,” I retort. “I know. I hear it enough. But why do people do things just because it’s been done that way before? What if something needs changing?”

“Patya-cha,” she says, “you will understand better when you are older.”

“Older?” The affectionate “Patya-cha” only annoys me even more. “I am not a little girl. I am old enough to understand that a boy can find water where men do not, that some people are evil and should never be trusted, that there are men who do things for no reason but to pleasure themselves with power. That the worst of them use the gods as an excuse. And you allow it! I am old enough to know that Paya Kuyllay would have preferred to be buried here. Here!”

My words echo against Mother’s silence. After a while, so softly that I can barely hear her, she says, “I miss her too, Patya, more than you know.” She turns and goes back inside. I want to rage at my mother, but my anger is losing its edge. Of course, I’ve noticed how she will catch herself mid-sentence, about to call to Kuyllay for something. The way she lingers at Kuyllay’s sleeping mat, stroking the shawl that still hangs next to it. The way the bed is still there, unchanged. I stare out over the valley. Kuyllay is gone. Anger will not bring her back.

I take a deep breath, close my eyes, and put my hand to my heart. “Mama K’illa,” I whisper, “light my way through this darkness.” I open my palm to the wind and blow my prayer to the heavens.

When I turn to go back inside, Mother is standing in the doorway with a small lamp. She gestures for me to follow her. Our shadows dance across the wall as she leads me to the back room. “Kuyllay left something for you,” she says. She has me sit, then reaches under a pile of furs and fabrics. The bundle she pulls out is wrapped in fine blue cloth. “Go ahead. Open it.”

I untie the cord carefully, unfold the delicate layers, and lift out a robe of white feathers. Beneath it is a silver mask with the face of an owl. Something in the air changes. A trembling, a sudden hiss from the lamp, a feeling I can’t name. Light ripples across the surface of the mask. It seems to breathe. I am entranced by the shimmering details in the owl’s face, the impeccable stitchwork on the robe, the sheen across the feathers that stir at my slightest breath. “It’s stunning,” I whisper. “I can’t imagine anything better for Ecco’s wedding.” With a costume like this, I can create a dance truly worthy of the ceremony that will unite my brother with my best—and only—friend, Faruka.

Mother places her hand over mine solemnly. “No, Patya. When the caravan gets here, we will get all the feathers you need to make a cape for the wedding dance. What you are holding now is consecrated for high ceremony, for stepping into the spirit world through a sacred, secret dance . . .”

The shadows lean a little closer. Feathers flutter and settle while I take in what Mother is saying. I watch her fingers flutter toward the mask, tracing the lines that shape the eyes, the beak, the embossed texture of feathers. It is a stunning mask. I can’t remember seeing anything so beautiful.

“The legacy of our ancestor Tuku Warmi, the Owl Woman,” she says in a reverent whisper, “is more than a legend. When the time is right, you will discover the purpose and the power of this gift.” She glances up at me. “Kuyllay said that the most difficult part for you will be the wait.”

I fold the tunic carefully, place the mask on top, and then arrange the cape, careful not to damage the long shoulder feathers. I rewrap them together in the blue cloth, tie the bundle, and hold it to my pulsing heart. It is heavier than it looks. I close my eyes and breathe in the smell of time, the hint of Kuyllay’s ceremonial flower water, the tickle of dust in my nostrils. The moment settles deep into my chest with the next breath. When I open my eyes, Mother’s soft brown eyes are watching mine, her forehead smooth and untroubled for the first time in weeks. I bow my head and say, “I can wait.”

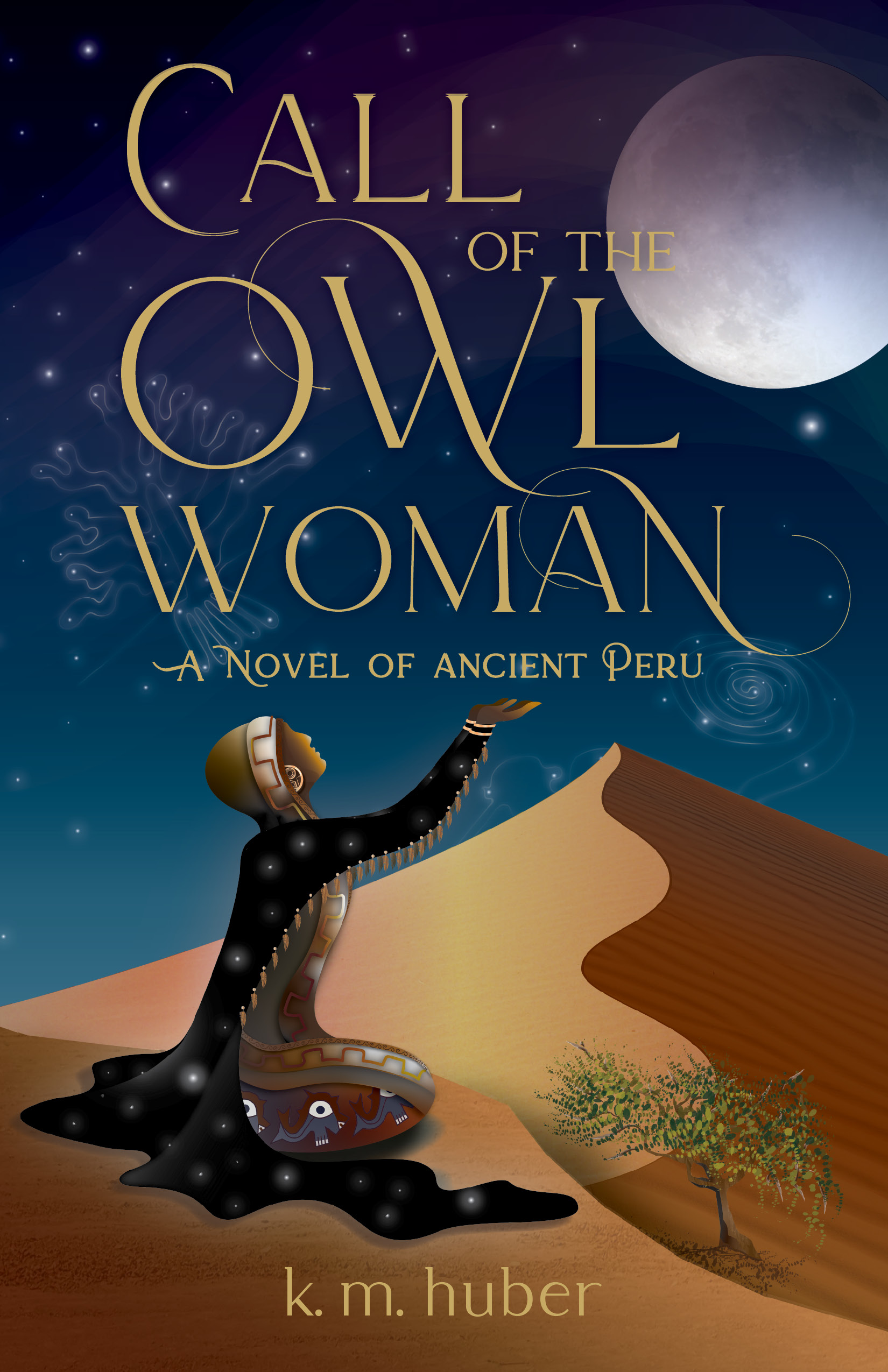

Call of the Owl Woman by k. m. huber is the first book of the Patya Trilogy, published by SparkPress May 13, 2025 and available through SimonandSchuster.com and all major booksellers.

***

k m huber grew up in the Pacific Northwest climbing trees, wandering in the mountains, wondering about the world, and writing poems. Unforeseen winds carried her to a new life in New York City, chance introduced her to her future husband, and before long another wind blew them together to the stark desert coast of his homeland, Peru. There, she fell under the enchantment of mystical inland Andean peaks, magical valleys, timeless tales and colorful traditions.

k m huber grew up in the Pacific Northwest climbing trees, wandering in the mountains, wondering about the world, and writing poems. Unforeseen winds carried her to a new life in New York City, chance introduced her to her future husband, and before long another wind blew them together to the stark desert coast of his homeland, Peru. There, she fell under the enchantment of mystical inland Andean peaks, magical valleys, timeless tales and colorful traditions.

While living in Lima, she dove into research about the Nasca, interviewed experts, walked its landscapes, climbed sacred hills, met some thousand-year-old guarango trees, and collaborated on a documentary about deforestation.

Huber’s writing can be found in Vice-Versa, Earth Island Journal, Post Road, Rougarou, The McGuffin, and Latin America Press, among others. Her fiction includes Patya y los Misterios de Nasca (La Nave, Peru 2023). She currently resides in Maryville, Tennessee with her husband and dog, still zooms with her Lima writer’s group, and enjoys being close to mountains again.

Steve Davidson is the publisher of Amazing Stories.

Steve has been a passionate fan of science fiction since the mid-60s, before he even knew what it was called.