An unofficial and unauthorized overview of The X-Files

(Parts 1 2 3 4)

Cautionary Note

If you’re looking for a treatise about the 2016-2018 reboot of The X-Files, which trashed both the human drama and the invention of the original 1993-2002 series, you’ve come to the wrong place.

Reboots have become the bane of popular entertainment on the screen, most notably in superhero comic epics, which play fast and loose with their invented histories. Often this reflects a turnover in writers and producers. But in the case of The X-Files and Twin Peaks (in a 2017 sequel) their original creators, Chris Carter and David Lynch, failed us. There is nobody else to blame.

In Dangerous Purpose is about the series that captured our imagination and, for all its faults, had something important to tell us. In its final seasons, and even the second movie spinoff, I Want to Believe (2008), it seemed to be pointing in an entirely different plan than that unfolding years later in the reboot. We deal here with what was, but also what should have been.

The rest is relegated here to an appendix.

(Editor’s Note: The Appendix is included at the end of Part 4.)

Part Two: Supporting Players

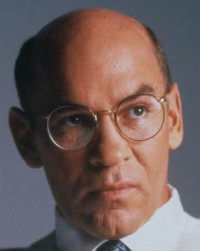

1. Walter Skinner

Every minute of every day we choose. Who we are. Who we forgive. Who we defend and protect. To choose a side or to walk the line. To play the middle. To straddle the fence between what is and what should be. This was the course I chose. Trying to find the delicate balance of interests that can never exist. Choosing by not choosing. Defending a center which cannot hold. So death chose for me.

– Skinner, soliloquy in “S.R. 819”

Notwithstanding its allusion to William Butler Yeats’ “The Second Coming” (“Things fall apart/The center cannot hold”), the soliloquy is as true to Walter Sergei Skinner as “To Be or Not to Be” is to Hamlet. Skinner has been given his own voice. And yet, it seemed at first that he had no true voice, or even a true will.

We first encountered him in “Tooms,” which had the added distinction of being the first episode to bring back a monster-of-the week. Skinner had called Scully in to answer for her work on the X-Files, and, as she later put it to Mulder, “reel me in.” He wanted her to do everything “by the book,” but with Cancer Man lurking in the background we surmise that wasn’t necessarily the FBI’s book he was talking about.

In the course of their investigation of murders committed by the shape-shifting Eugene Victor Tooms, Mulder and Scully went out of bounds, and Tooms even tried to frame Mulder for assault. This time, they were both called in by Skinner, who wanted them off the case. Summoning Mulder aside, the assistant director admitted that he was “one of the finest, most unique agents” in the history of the bureau, but advised him to give the X-Files a rest. It was only at the very end of the episode that we saw him as any more than an enforcer for Cancer Man:

SKINNER: You read this report?

(Cancer Man walks towards the window. Skinner looks at him.)

Do you believe them?

CANCER MAN: Of course I do.

Skinner had been a skeptic of the paranormal until then, at least outwardly. Did Cancer Man give him pause? We don’t know why he would have given credence to the X-Files when he is so obviously intent on shutting them down – he got his wish (for the first time) in “The Erlenmeyer Flask.” Skinner didn’t even appear there, and was mentioned only once – as the bearer of the bad news from “the top of the executive branch.”

Skinner returned in “Little Green Men,” seemingly still under Cancer Man’s thumb as he supervised Mulder and Scully – who were forbidden to have any contact with each other – on routine work. When the game was afoot, however, Mulder managed to sneak off to Puerto Rico to check out possible alien contact at Arecibo, and Scully contrived to find a way to follow him. In the aftermath, we saw them back in Skinner’s office with Cancer Man again lurking behind the assistant director as he read Mulder the riot act for leaving his assignment – a bank fraud investigation that for some reason involves surveillance tapes about a strip joint.

Mulder was contrite, admitting that his walkabout “warrants disciplinary action,” but arguing that he already had enough evidence in the bank fraud case, and complaining about his phone being illegally wiretapped while he was away. This last is news to Skinner, who “looks at [Cancer Man] in shock.” Cancer Man seemed confident that it didn’t matter as he approached Mulder to taunt him:

CANCER MAN: Your time is over… and you leave with nothing.

SKINNER: Get out.

For a moment, we assumed that Skinner was talking to Mulder. So did Cancer Man himself. Only when Skinner glared at Cancer Man and repeated his order did we get it. Cancer Man slunk out of the office. Nothing else seemed to come of the confrontation; Skinner sent Mulder back to work on the bank fraud case. And yet we saw a revelation. We knew that Skinner hated Cancer Man, hated being used by him and his (yet unseen) fellow conspirators.

Skinner still officially kept a tight leash on Mulder, but we coukd sense now that this was actually to protect him (“If you’re having trouble sitting on Mulder, Assistant Director Skinner, I’m sure you know we’d have no trouble,” Cancer Man warned him early on in “One Breath.”).

But we could believe that Skinner was a man of honor, forced into a dishonorable role – and this was the key to his characterization throughout the series. He felt a strong sense of personal violation, and an equally strong sense of personal guilt for allowing himself to be violated, for his failure to commit himself wholeheartedly to what he knew is right. And yet he would do the right thing when he could – as with ordering the reactivation of the X-Files in “Ascension,” after learning of Alex Krycek’s treachery and his association with Cancer Man.

He could even play the father figure. When Mulder, in a moment of despair, tendered his resignation in “One Breath,” Skinner refused to accept it, telling of his disillusionment as a young Marine in Vietnam (“I lost my faith. Not in my country or in myself, but in everything. There was just no point to anything anymore.”) – and then revealing a near-death experience he could neither explain nor accept: “I’m afraid to look any further beyond that experience. You? You are not. Your resignation is unacceptable.”

It is only at that moment that Mulder realized what Skinner had already done for him, and the assistant director’s response revealed a streak of world-weary fatalism that also seemed an essential part of his character:

MULDER: You.

(Skinner turns back. Mulder sighs.)

You gave me Cancer Man’s location. You put your life in danger.

SKINNER: Agent Mulder, every life, every day is in danger. That’s just life.

Yet he could still take comfort and even pleasure in his triumphs, however fleeting they may turn out to be – as in the scene in “Paper Clip” where, after having been beaten up and robbed of the MJ file by Krycek and Luis Cardinale, he faced up to Cancer Man – seeking to exchange the tape he doesn’t have for the safety of Mulder and Scully.

“You haven’t got any tape,” Cancer Man taunts him. “You haven’t got any deal. You can’t play poker if you don’t have any cards.”

Only Skinner does have some cards, or at any rate a good bluff. “This is where you pucker up and kiss my ass,” he tells his adversary as he introduces Albert Hosteen, the Navajo he says has memorized the contents of the tape, and shared its secrets with 20 other members of his tribe: “Welcome to the wonderful world of high technology.”

Chances are it is a bluff, since nothing more is heard of it for the rest of the series. But because (Welcome to the wonderful world of plot implausibility!) the documents in the files were written in Navajo, it just might not be a bluff. In any event, Cancer Man decided he couldn’t risk calling it, and beat a silent retreat.

In later encounters, Skinner refused to be intimidated, even when he should have been, as with the case of the stolen diplomatic pouch in “Tunguska” that contains reports of Russian research on a vaccine against the Black Oil. Cancer Man shows up outside his new apartment building, but Skinner won’t even stop walking as his former nemesis tries to put a scare into him:

SKINNER: I don’t know anything about a diplomatic pouch.

CANCER MAN: No? Nothing about the matter?

SKINNER: No.

CANCER MAN: Well, I find that hard to believe. As their supervisory agent. As a friend, I should advise you, Mr. Skinner, that withholding information on matters of national security is punishable under the laws of this country for treason and sedition.

SKINNER: Thank you. I’ll consider myself advised. As a friend.

By this time, Skinner may have had even less love for Krycek than for Cancer Man, given their past. When Mulder showed up looking for a safe place to stash the former Syndicate agent and now free-lance troublemaker in the same episode, Krycek had the nerve to ask whether the assistant director’s apartment is really safe.

“Relatively safe,” Skinner responded, punching him in the gut. And in one of the truly classic Skinner scenes, he cuffed Krycek to the balcony of his apartment. It’s high up, and it was cold and windy out there:

KRYCEK: You can’t — you can’t leave me out here, I’m going to freeze to death!

SKINNER: Just think warm thoughts.

But for every moment of triumph, there was another moment of indignity, and even moral compromise. Perhaps the most dramatic involving Mulder came in “Memento Mori,” when Scully’s cancer – the result of removal of her alien implant – had taken a serious turn.

Desperate to find a cure at any cost, Mulder came begging to Skinner to put him in touch with Cancer Man. “You deal with this man, you offer him anything and he will own you forever,” Skinner warned him, but Mulder wouldn’t be dissuaded.

MULDER: We are talking about Agent Scully’s life.

SKINNER: Find another way.

But what Mulder never learned was that Skinner himself contacted Cancer Man a short time afterwards to make a deal to save Scully’s life. Cancer Man, of course, didn’t miss a chance to sneer at him for playing patron to Mulder while consigning him to a basement office. But while Skinner could still respond with a barbed remark, it now rang hollow:

SKINNER: At least he doesn’t take an elevator up to get to work.

CANCER MAN: You think I’m the devil, Mr. Skinner.

It rang even more hollow when Mulder called to tell him that Scully seemed to be improving, that they hope for a cure – and to thank him for his advice to find another way. In an act of ironic betrayal, Skinner has sacrificed what he holds most dear – his moral integrity – to save Mulder’s.

In “Zero Sum,” Skinner had to repay Cancer Man by doing his dirty work for him – disposing of the body of Jane Brody, a victim of the Syndicate’s experiments with using bees to spread the black oil virus. He also pretended to be Mulder to get hold of the pathology report on her and a blood sample – and had an embarrassing encounter with the detective who had e-mailed Mulder about the case in the first place.

The detective, whose message had been deleted by Skinner, turned up dead himself – shot with a gun stolen from the assistant director. Skinner was in deep shit, and when Mulder figured out what had been going on, he assumed that his boss had been working for his enemy all along. In a bitter irony, it turned out that Cancer Man never intended to hold up his part of the deal. When Skinner realized this, he threatened to kill his nemesis:

SKINNER: Agent Scully is dying, and you haven’t done a damn thing about it. (Cancer Man smirks) You think that’s funny?

CANCER MAN: I’m just enjoying the irony, Mr. Skinner. Only yesterday, you said you wouldn’t be a party to murder and now here you are. Yours isn’t the first gun I’ve had pointed in my face, Mr. Skinner. I’m not afraid to die. But if you kill me now, you’ll also kill Agent Scully.

SKINNER: You have no intention of saving her. You never did.

CANCER MAN: Are you certain? I saved her life once before, when I had her returned to Agent Mulder. I may save her life again. But you’ll never know if you pull the trigger, will you?

And Skinner didn’t. Even though he had managed by this time to convince Mulder that he was framed, he must have felt utterly ashamed. Cancer Man, of course, went on to provide Mulder himself with a new implant to cure her – in hopes that Mulder would switch sides. But Mulder avoided the trap, which also included another false Samantha as bait.

Skinner was the only major character on The X-Files to suffer a guilty conscience. He always reproached himself, never more so than in “S.R. 819,” where he was infected with nanobots that were choking the life out of him:

SKINNER: I’ve been lying here thinking. Your quest… it should have been mine.

SCULLY: What do you mean?

SKINNER: If I die now, I die in vain. I have nothing to show for myself. My life…

SCULLY: Sir, you know that’s not true.

SKINNER: It is. I can see now that… I always played it safe. I wouldn’t take sides. Wouldn’t let you and Mulder… pull me in.

SCULLY: You’ve been our ally more times than I can say.

SKINNER: Not the kind of ally that I could have been.

With Skinner, it was always personal, whether in dealings with Mulder and Scully – or Alex Krycek, his new nemesis, the man controlling the nanobots. At the end of that very episode, Skinner knew he could no longer be an ally to Mulder and Scully – at least, not when Krycek said otherwise.

Mulder was more forgiving of Skinner than Skinner could be of himself. “Look… I know you’ve been compromised,” he told him in “The Sixth Extinction.” “I know Krycek is threatening your life.”

Yet where Krycek’s interests aren’t involved, Skinner could show increasing loyalty to Mulder and Scully. Not until “Requiem” did he see with his own eyes what Mulder had pursued for years and, true to form, he blames himself when Mulder is abducted: “I lost him,” he tells Scully. “I don’t know what else I can say. I lost him. I’ll be asked… what I saw. And what I saw, I can’t deny. I won’t.”

Only in “Within,” it was Scully herself who warned him against telling what he saw. That he can understand her, that he knows that Alvin Kersh – now promoted to deputy director – will give him the gate if he shows any sign of embracing Mulder’s truth, can’t soften the humiliation he must feel once again.

Yet if he couldn’t defend the legacy of Mulder, he could still defend Scully – and, after learning about her pregnancy, her unborn child. When, in “Deadalive,” Mulder seemed to be lost forever, he somehow sensed, at the graveside in the dead of winter, that Mulder’s family and his work were not:

SCULLY: He was the last. His father and mother… his sister… all gone. I think the real tragedy… is that for all of his pain and searching… the truth that he worked so hard to find was never truly revealed to him.

(Skinner looks down at her, listening.)

SCULLY: (her voice begins to break) I can’t truly believe that I’m really standing here.

SKINNER: (softly) I know. And I don’t truly believe that… Mulder’s the last.

It’s personal between him and Mulder and Scully. At the end, it was still personal, as Krycek attempted to kill Mulder after coming up with yet another story about the alien replicants and arguing that either he or Scully’s baby has to die:

MULDER: You want to kill me, Alex, kill me. Like you killed my father. Just don’t insult me trying to make me understand.

(Krycek’s finger slowly and reluctantly tightens on the trigger. His face is contorted with indecision. Mulder is calm. He and Mulder stare at each other. A gun is fired. Krycek gasps in pain and falls, dropping his gun. There is a bullet wound in his right arm. He looks up and sees Skinner a few yards away, gun in hand. Krycek reaches down to pick up his gun and screams in pain and falls to the ground again as Skinner shoots him in the right arm again. His arm is now useless. Weakly, Krycek uses his prosthetic left arm to push his most definitely unregistered gun toward Skinner.)

KRYCEK: It’s going to take more bullets than you can… ever fire to win this game. But one bullet… and I can give you a thousand lives.

(He looks up at Mulder.)

KRYCEK: Shoot Mulder.

(Skinner looks at Mulder. Mulder looks at Skinner. Skinner raises his gun and fires. Krycek, the Ratboy, falls to the ground, a bullet hole between his eyes.

It should have ended there, just as the series might have better ended with the birth of Scully’s son. In the final season, Skinner and others had to suffer under Brad Follmar and Toothpick Man – the latter a replicant who has somehow gained the same influence over the FBI once held by Cancer Man. Only he’s no Cancer Man, or even a Krycek.

Although Skinner was supportive of Mulder in “The Truth,” the situation was simply too contrived for his role to be credible. But we got to see the real Skinner again, at last, in I Want to Believe – doing the right thing when it most needed to be done. We should be thankful for that. It reminds us that relationships like that between Skinner and Mulder could be male bonding at its best.

2. The Lone Gunmen

Those were the most paranoid people I have ever met. I don’t know how you could think that what they say is even remotely plausible.

— Scully, in “E.B.E.”

Even Fox Mulder treated the Lone Gunmen as something of a joke when he first met them in “E.B.E.” – this was in the first season, long before their origin story in “Unusual Suspects.” In their short-lived spin-off series, they became a pathetic joke. And yet they became heroes in the end, in an episode quite inappropriately titled “Jump the Shark.”

The Lone Gunmen were introduced as comic relief, an element of self-parody in the conspiratorial world of The X-Files. We couldn’t imagine at first how such disparate types as the buttoned-down John Fitzgerald Byers, the middle-aged letch Melvin Frohike and the seeming Wayne’s World fugitive Ringo Langly ever managed to get together. We didn’t even know their first names – and it was only late in the series that Langly’s came out.

How were we supposed to take the Lone Gunmen? Pretty much the same way Mulder took them:

BYERS: And, Mulder, listen to this. Vladmir Zhirinovsky, the leader of the Russian Social Democrats? He’s being put into power by the most heinous and evil force of the 20th century.

MULDER: Barney?

Even in episodes as grim as “Blood” – their second appearance, which involves a terrifying mind control program like something out of The Manchurian Candidate – the Gunmen are hard to take seriously.

BYERS: In our April edition of The Lone Gunmen, we ran an article on the C.I.A.’s new CCDTH-twenty-one thirty-eight fiber-optic-lens micro-video camera.

LANGLY: Small enough to be placed on the back of a fly.

MULDER: Imagine being one of those flies on the wall of the Oval Office.

But they also became all-purpose experts, playing almost a deus ex machina role. Even in “E.B.E.,” Langly somehow forges passes to get Mulder and Scully into a top-secret government facility where an alien is supposedly being held. In “One Breath,” all three of them are there to provide an explanation for what has happened to Scully:

BYERS: The Thinker reports the protein chains are a result of branched DNA.

MULDER: Branched DNA?

LANGLY: The cutting edge of genetic engineering.

BYERS: A biological equivalent of a silicon microchip.

LANGLY: This is way beyond cutting edge. This technology’s fifty years down the line.

MULDER: What’s it used for?

FROHIKE: Could be a tracking system.

LANGLY: Or something as insidious as grafting a human into something… inhuman.

But as the Gunmen became privy to the secrets of the Conspiracy, they should also have become targets of the Conspiracy. Cancer Man offered several explanations as to why he was protecting Mulder. But nobody was ever protecting the Gunmen. When the Thinker gets hold of the MJ file in “Anasazi,” his fate is sealed. But not that of Byers, Frohike and Langly, even though they too are in the thick of things.

Why?

Perhaps because nobody could take them seriously. Precisely because they were seemingly just comic characters, they weren’t seen as a threat to the Conspiracy. Nobody would believe anything they said, even if they went to the media with solid evidence. Deep Throat and X never did that, but they paid with their lives for helping Mulder.

True, in “Musings of a Cigarette Smoking Man,” Cancer Man has Frohike in his sights but forebears to pull the trigger. Yet, as we shall see, there is reason to believe that the episode was apocryphal. That was why Cancer Man couldn’t go through with killing the man who had supposedly learned the truth about him. “I can kill you whenever I please,” he muses. Yet he never pleased.

We never learned the names of Mulder’s martyred informants, but we know that Deep Throat – who was buried at Arlington National Cemetery – was a mover and shaker with both the Syndicate and the CIA. We know that X had connections with Marita Covarrubias and, most likely, the Syndicate. They were somebodies. The Gunmen were nobodies.

Except to us. We came to love them for their eccentricities and their foibles. There was Frohike, who had a crush on Scully (“She’s hot.”). Before that, he’d tried to pass himself off to Suzanne Modeski in “Unusual Suspects” as just the man she needed to take care of Mulder, who – so Modeski told him – had kidnapped her daughter:

SUSANNE: Bad idea. He’s very dangerous.

FROHIKE: Lady, I’m dangerous.

In the same episode, Frohike and Langly were business rivals at a consumer electronics show, taking Modeski for a potential customer:

LANGLY: Hey lady, if you want to watch Matlock with Andy Griffith all blue and squiggly, go right ahead and buy from this guy. But, if you want quality bootleg cable, you talk to me.

FROHIKE: If you want a converter that’ll short out and burn your house down, definitely talk to this guy.

In “Like Water for Chocolate,” the best episode of their short-lived spinoff series, we also got flashbacks to their teen years, with ironic legends on the screen:

When I grow up I want to be a career bureaucrat with the Federal Government. I want to help as many people as I can and work hard to spread democracy throughout the world.

(John Fitzgerald Byers, idealist)

Let me tell you something about this damn-fool toy, Dad. This damn-fool toy is gonna change everything. From the way people do business to the way we communicate. This damn-fool toy is the future. And you know what else – by the year 2000 when I’ve made millions of dollars off this damn-fool toy we’ll all eat food pills like on Star Trek and we won’t need cows anymore.

(Richard “Ringo” Langly, Computer God)

I think big, see. Bigger than you. I’m gonna do big things and then I’m gonna write about them. People will hang on my every word. Yeah. I’ll be a crusading publisher and make the world a better place. Like – like – like Hugh Hefner. Yeah.

(Melvin Frohike, Man of Action)

While the series theoretically gave the Gunmen a chance to shine, they couldn’t be at their best without Mulder and Scully as straight men. To fill that gap, the show gave them Jimmy Bond – a complete idiot, but a well-heeled complete idiot who could underwrite their operations. In “Like Water for Chocolate,” where the Gunmen seem to have been killed in the search for a car that can run on water, Bond compares them to other great heroes while making an utter fool of himself:

Heroes. Once in a great while they come along when we need them most. Like President Churchill who won World War II, and Gandhi the peaceful leader of the Indians or as we know them, Native Americans.

While Bond’s idiocy had its charm, that charm inevitably wore off. What was worse, too many of the episodes had the Gunmen coming off as a bunch of rubes, and as the butts of gross-out jokes. In the last episode, “All About Yves” (Yves Adele Harlow was a femme fatale), they ended up entrapped by Morris Fletcher (he of the X-Files “Dreamland” episodes, which may have been a dream) in a disastrous caper that ends up with the lot of them arrested and Langly with blue dye on his face.

Langly still hadn’t been able to wash off that blue dye when the Gunmen returned to The X-Files in “Nothing Important Happened Today.” What’s worse, they’d been totally wiped out financially – they even had to borrow computers. Even worse than that, they failed Scully in “Provenance,” when they were entrusted with her baby William, only to let him be abducted by a UFO cult. It seemed that Byers, Frohike and Langly were no longer good for anything but pity.

And then came “Jump the Shark,” in which John Gilnitz – previously referred to by Fletcher in “Dreamland” as an actor who was supposedly installed in Iraq by the CIA to pose as Saddam Hussein – turns out to be a real terrorist, and a suicide bomber at that. Only his bomb is a vessel implanted in his stomach that, when it decays, will release a virus that could kill thousands of people for miles around, and will surely kill all the scientists at an International Bioethics Forum.

The Gunmen manage to trap Gillnitz in a corridor outside the conference hall, but it’s too late to neutralize the bomb, which will go off in less than two minutes. Gillnitz knows it, and taunts them about it, certain that nothing can stop him now.

.GILLNITZ: Now you have a minute forty.

(The Gunmen stand there for a moment, contemplating their options. Frohike notices a fire alarm switch on the wall. He turns to the others, signaling his intention.)

FROHIKE: Guys?

(Langly and Byers look at the fire alarm, then at each other. In silence, they both agree with Frohike’s suggested course of action.)

BYERS: Whatever it takes.

(Gillnitz stands in silence, waiting for their next move. Frohike looks back at him, before reaching for the switch, activating the fire alarm. The siren sounds.)

(Suddenly, thick fire doors descend from the ceiling, completely blocking off the exits in the corridor. Gillnitz looks on in shock, realizing what they have done. He races over to one of the closing doors, but it reaches the ground before he can get to it. His plan is now thwarted. The corridor is now airtight, and the Gunmen are trapped inside.)

Whatever it takes. We are reminded of Todd Beamer’s “Let’s roll,” as he led the charge against the hijackers of Flight 93 on 9/11. The Gunmen end their lives as true American heroes, neither swaggering Rambos nor self-pitying whiners. We feel sad for them, but proud of them.

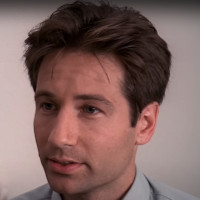

3. Loyal as a Doggett

When Chris Carter was forced to come up with a new partner for Dana Scully in the seventh season, he truly rose to the occasion. John Doggett is nothing whatever like Fox Mulder. His whole background, his whole temperament, is different.

Ex-Marine, ex New York City cop, he was all business when he was assigned by Alvin Kersh, the new deputy director at the FBI, to head a task force searching for Mulder. Like Mulder, however, he grew on us as we learned more about him, and earned our respect in spite of his seeming brashness.

Kersh, of course, believed that Mulder had simply disappeared – he won’t hear anything about alien abductions. As for Scully, she was contemptuous of Doggett from the get-go, pouring a cup of water over his head after – without even introducing himself – he started treating her condescendingly, as if he knew more about Mulder than she does.

When she suspected that her phone is being tapped, she called him up at home and chewed him out. But the thing is, Doggett’s an honest cop, who knows a rat when he smells one, as in a memorable scene with Kersh:

KERSH: In Vietnam we used to fly night sorties ten feet above the treetops. Before night vision, before fly-by-wire. Six hundred miles an hour and all we had was an idiot gauge and our wits. Guys used to say they only knew their altitude by the smell of the V.C. rice pots.

DOGGETT: You’ve come a long way, sir.

KERSH: Using all the same instincts. What can I do for you, Agent?

DOGGETT: This task force– the search for Mulder, I’m running it, right?

KERSH: You’re the man in charge.

DOGGETT: No one else is involved? Someone out there acting under orders from another office?

KERSH: I think I’d know, Agent. What prompts the question?

(Doggett looks directly at Kersh.)

DOGGETT: My idiot gauge. My wits.

Scully, once the skeptic but now a believer in the paranormal, was partnered with him on the X-Files. That was no simple role reversal, however; rather a whole new relationship, and Carter made brilliant use of it in their early episodes together – especially “Invocation.”

Faced with an obviously paranormal situation – a boy who’s been missing for ten years yet mysteriously reappears without having aged – Doggett would seem to be totally out of his element. Rather than argue endlessly with Scully about the nature of the case, however, he simply ignored the supernatural aspects – interviewing Billy Underwood as if he were a conventional kidnap victim.

DOGGETT: How you doing, Billy? My name’s John. I’m gonna have a seat over here, is that okay? Is that all right?

(Doggett sits at the table. Billy doesn’t say anything, just keeps drawing a strange symbol on a piece of paper with a black magic marker.)

DOGGETT: Billy, I want you to know that you’re not alone. I’ve talked to lots of other boys and girls who’ve been hurt just like you. Sometimes when they talk about it the hurt starts to go away. You want to talk about it, Billy?

(No response. Scully and the Underwoods are watching.)

DOGGETT: You know, maybe you think bad things happened to you because you’ve been a bad boy… but I’m here to tell you, that’s not true. The bad guy is the one who took you away and it’s up to you and me to get the bad guy. See, ‘cause as big and tough as I am, I can’t do it alone. I need your help. Can you tell me about him, Billy? What’s his name? What did he look like?

When he follows up an old lead on a suspect, again it’s standard police work. Never mind that the boy mysteriously appears and disappears, that a bloody knife appears out of thin air, that a psychic shows stigmata of that strange symbol.

And, amazingly, Doggett breaks the case, even if it isn’t the case he thought it was, and saves Billy’s brother Josh from the same kidnapper – even though he’s faced at the end with the revelation that Billy was killed ten years earlier and that he and Scully have been dealing with some sort of ghostly manifestation. Scully, who herself never got to solve a case that way, offers what comfort she can:

SCULLY: Look, I know where you are with this. I have been there. I know what you’re feeling– that you’ve failed and that you have to explain this somehow. And maybe you can.

DOGGETT: Not if that’s Billy’s body, I can’t.

SCULLY: But maybe that’s explanation enough. That that’s not Billy’s brother lying in that grave, too. That man who did this is never going to be able to do it again. Isn’t that what you wanted, Agent Doggett?

We learned that Doggett’s own son Luke had been kidnapped years earlier – a case that had not been solved at the time he met Scully. The strain of that loss had destroyed his marriage with his wife Barbara, but the case was finally solved in “Release.” It was nothing like the case of Samantha Mulder: no alien abductors, just brutal criminals – the kind cops deal with day in and day out.

The problem with Doggett as the season progressed was that too much was thrown at him for his skepticism to remain credible (Scully usually wasn’t an eyewitness to the paranormal in her years as a skeptic; even so, her skepticism was far too prolonged.). He was still questioning the existence of aliens after his encounter with a shapeshifter at the outset and an ET slug in “Roadrunners.” He experienced possession by a demon in “Via Negativa,” and being shot to death, consumed by a monster and regurgitated good as new in “The Gift.”

Only in “Vienen,” after the return of Mulder, was Doggett finally won over. Perhaps that was Carter’s plan all along. Despite all that, Doggett was great in other stand-alone alone episodes, especially those like “Redrum” that told us more about his background. But Carter should have sketched an outline for his transition from skeptic to believer.

As for his partnership with Scully, their very lack of conventional chemistry was a sort of chemistry – they were doing a sort of wary dance around each other. Eventually, they learned to trust each other as agents.

But there was a new dynamic on The X-Files with the arrival of Monica Reyes, an agent who was teamed with Doggett despite the fact that – unlike him – she had long been a believer in the paranormal. Her background was unlike that of any of the other agents working on the X-Files: born in Mexico, majored in folklore and mythology in college, took a master’s degree in religious studies.

While serving in the New York City field office, she had been lead investigator into the murder of Luke. She failed to find his killers then, but her work impressed Doggett enough for him to call her in to assist in his own investigation into the disappearance of Mulder and the Bellefleur abductees. Having previously specialized in Satanic cults, she theorized that a cult must be involved in the supposed alien abductions. She stayed with the case until after Mulder was found, but returned to the New Orleans field office shortly afterwards.

She surfaced again in “Essence” and “Existence,” helping Scully find a safe place to give birth (although the alien replicants show up anyway) and even helping deliver her baby under extraordinarily difficult circumstances. That led Doggett to recruit her for the X-Files, and she became a regular in the final season.

In “Release,” she played a role in solving the mystery of Luke Doggett’s murder – with the unlikely assistance of an escaped mental patient who posed as an FBI cadet and put Doggett and Reyes to shame in profiling the killer of two Maryland women. “Cadet Hayes” was psychic, of course, but the real story had to do with how Brad Follmer, yet another assistant director, turned out to have known all along that the boy was killed by Nicholas Regali, a mobster Follmer was in bed with back in New York.

At the end, Doggett was about to kill Regali, but a remorseful Follmer did it for him – knowing that a tape showing him taking a bribe from the mobster would surface and end his career. Doggett and his former wife Barbara finally have closure, and shared a tender moment casting Luke’s ashes into the sea. But it is Reyes in whose arms he found comfort afterwards, and we sensed they might have a future together.

Reyes had had an affair with Follmer in New York – contrary to FBI regulations – although it is hard to imagine what she saw in him before she caught him taking a bribe (She never reported it at the time.). In his new post at FBI headquarters, Follmer came off as obnoxious in his dealings with Doggett (addressing him as “Mr. Doggett” instead of “Agent”) as well as Scully, and seemed to be toadying to Deputy Director Kersh – who in turn came off as an enemy to Doggett and Reyes.

Kersh, who may still be associated in many fans’ minds with the final two seasons, had actually made his first appearance in “The Beginning,” the sixth season opener in which Mulder and Scully were taken off the X-Files and told him report to him. But he appeared in only six episodes that season, making no impression beyond that of an officious obstructionist.

Because he disappeared entirely in the seventh season, it came as a surprise when he reappeared in the eighth as a commanding figure – and not just because he had been promoted from assistant director to deputy director. He showed himself to be a stern taskmaster – like Walter Skinner in the first season.

Again like Skinner before him, Kersh finally proved which side he was really on by slipping information to the man who trusted him least. In “Nothing Important Happened Today,” Doggett was convinced that Kersh’s hands were “filthy” in the Super Soldier case. Yet he also believed that it was Kersh who slipped him a vital clue: the obituary of Carl Wormus.

Kersh responded with a well known anecdote about King George III, whose diary entry July 4, 1776 was “Nothing Important Happened Today.” But Doggett still didn’t get it, so the deputy director has to spell it out:

KERSH: Revolutions start, things that change the world forever, and even Kings can miss them if they’re not paying attention.

DOGGETT: Are you saying that you left that obituary to help me? To help me find the things that I found? Nah, why would I believe that you’d help me?

KERSH: Agent Mulder believed me.

DOGGETT: Mulder? What the hell are you talking about? Mulder’s long gone.

KERSH: Say I told Mulder that he would be killed if he stayed. The same people who threatened to kill me if I didn’t go along. Would you believe that John?

DOGGETT: No. Mulder wouldn’t hear it, not from you, not from anybody.

KERSH: I said I told him to go. I didn’t say I persuaded him.

DOGGETT: Oh my God. It was Scully. Scully made him go. That’s it isn’t it?

And in “The Truth,” he was the one who urged Mulder and Scully to flee.

KERSH: You’ve got to move out.

SCULLY: What’s he doing?

KERSH: What I should have done from the start. You want to go north to Canada. Get to an airport. If you’re not off the continent in 24 hours you may never get out, you understand?

Only Mulder and Scully don’t go to Canada. They drive instead to Arizona in search of a Navajo wise man who has sent Mulder a tip that led him to a military base at Mt. Weather — and his discovery there of the date of the alien invasion. But the informant is neither a Navajo nor a wise man, but Mulder’s old nemesis Cancer Man.

4. Cancer Man

In the end… a man finally looks at the sum of his life to see what he’ll leave behind. Most of what I worked to build is in ruins and now that the… darkness descends, I… find I have no real legacy.

– Cancer Man, En Ami

Satan is often called the Father of Lies, and Cancer Man proved himself Satanic even in “En Ami,” the episode scripted by William B. Davis that is supposed to tell us his side of the story. As C.G.B. Spender, he tries to win Scully’s sympathy by telling her he has developed a miracle medicine that can halt aging as well as cancer.

But from the start of his conversation, we could tell that he was dissimulating when he told her about his fatal illness: “Cerebral inflammation — a consequence of brain surgery I had in the fall. The doctors give me just a few months.” From “Amor Fati,” we know what that “brain surgery” was all about, and if Scully knew she’d probably kill him on the spot. Only she doesn’t even know enough to ask him about that.

SCULLY: What the hell are you doing?

CANCER MAN: God’s work, what else?

As it was with Carter turning Skinner from an image into a character, so it was with Cancer Man – one of the greatest villains in the annals of the small screen. Good and evil, or somewhere in between, the supporting characters of The X-Files were essential to its appeal.

One point about Cancer Man has to be made at the outset. Well, two points: he was always officially Cigarette Smoking Man, even after he was given an identity as C.G.B. Spender (And, no, not even William B. Davis was ever told what the initials stood for.). Mulder called him Cancer Man, as did many fans, and the epithet seems of symbolic importance: Spender isn’t just a man who smokes, but a cancer gnawing at everything good and true and decent.

But that is only the minor point. The major point is that “Musings of a Cigarette Smoking Man” has to be considered apocryphal. Not because it plays fast and loose with the life of the character, reducing him at the end to a failed writer of cheap spy novels, but because it plays fast and loose with the chronology of the series.

In “Musings,” it is asserted that Cancer Man was born in 1940. But that would have made him only 13 in 1953. Craig Warkentin, who played the young Cancer Man in “Apocrypha,” was obviously at least ten years older than that. But the clincher was that Davis dubbed Warkentin’s dialogue for the scene where the young Cancer Man and the young Bill Mulder betray the dying sailor. Whatever else happened between 1953 and the later events of the series, this is history.

We simply can’t rely on “Musings of a Cigarette Smoking Man” as canon. Even in other episodes, we simply can’t rely on what Cancer Man has to say. He tells people at least three different stories about why he has kept Mulder alive.

The first comes in “Ascension,” as a response to Alex Krycek:

KRYCEK: If Mulder is such a threat, why not eliminate him?

CANCER MAN: That’s not policy.

KRYCEK: It’s not? After what you had me do?

CANCER MAN: Kill Mulder and you risk turning one man’s religion into a crusade.

In “Anasazi,” he offers the same explanation to Bill Mulder, but with a veiled hint that Bill had better keep his mouth shut if he wants his protection of Fox to continue:

BILL MULDER: You wouldn’t… harm him?

CANCER MAN: I’ve protected him this long, haven’t I? Your son has been provident in the alliances that he’s created. The last thing we need is a martyr in a crusade.

Clearly Cancer Man didn’t trust Bill, because his hit man Alex Krycek was already on the way. In “Herrenvolk,” he offered the Alien Bounty Hunter – who, like Jeremiah Smith, turns out to have miraculous healing powers – a variant argument for saving the life of Mulder’s mother Teena, who has suffered a stroke that may have been caused by the very stress he himself has inflicted on her:

You see… the fiercest enemy is the man who has nothing left to lose. And we both know how valuable Agent Mulder is to the equation.

Did Chris Carter have any idea of Mulder’s role in “the equation” at the time? It seems doubtful, and chances are that Cancer Man was obfuscating. In any case, two years later he has no further interest in saving her – she commits suicide. But by then he had a new explanation for not having done away with Fox Mulder – an explanation that doesn’t make any sense unless he could have miraculously foreseen the circumstances of “Amor Fati:”

CANCER MAN: All these years… all the questioning why… why keep Mulder alive? When it was so simple to remove the threat that he posed?

PROJECT DOCTOR: There was no way you could have predicted this.

CANCER MAN: The fact remains, he’s become our savior. He’s immune to the coming viral apocalypse. He’s the hero here.

PROJECT DOCTOR: He may not survive the procedure.

CANCER MAN: Then he suffers a hero’s fate.

Only the operation doesn’t work. When next we saw Cancer Man, he claimed to be terminally ill. He was lying about how much time he had, even if his health was indeed declining into the decrepitude we witnessed in “Requiem.” The failure of his surgery may explain why he lost access to the corridors of power by that time. His desperate attempt to revive the Project without that access leads to his apparent death at the hands of Alex Krycek and Marita Covarrubias. Yet in “The Truth,” he has one last bow – and one last version of why he kept Mulder alive:

My power comes from telling you. Seeing your powerlessness hearing it. They wanted to kill you, Fox. I protected you all these years … waiting for this moment … to see you broken. Afraid.

What is truth? Like Pilate, we have asked that question but, unlike the procurator of Judea, we have asked it over and over, and stayed for an answer. If we can’t trust anything Cancer Man ever says, we have to infer the truth by reading between the scenes and seeing between the scenes.

One thing that seems clear is that, while he is associated with the Syndicate, he certainly doesn’t lead it – and isn’t necessarily even one of the Elders. The First Elder sometimes treats him as if he were just an errand boy, and when he later orders Cancer Man’s execution, the action is both callous and casual.

Yet Cancer Man has a power base of his own at the Pentagon, and not just because he can hide evidence of aliens there: he commands the special forces that harry Mulder and Scully in “Anasazi” and “The Blessing Way;” and in Fight the Future he seems to be the man in charge of the Antarctic base. He has unrestricted access at FBI headquarters, and perhaps also at the CIA and the State Department. Yet he lives modestly, unlike the Elders – some of whom, at least, are members of the horsey set.

There is little love lost between Cancer Man and the Elders, especially the Well-Manicured Man, as witness their encounter in “Tunguska.” The Well-Manicured Man, who deliberately keeps out of phone reach at his horse farm in Charlottesville, Virginia, has forced Cancer Man to schlep all the way down there to report that a man answering Mulder’s description has somehow managed to get diplomatic passage to Krasnoyarsk, near where the Russians are doing their research on the black oil

WELL-MANICURED MAN: You fool, you stupid fool! This must be corrected; this must be handled!

CANCER MAN: Well, of course it can be! You know my capabilities in a crisis.

WELL-MANICURED MAN: I don’t think you realize what’s at stake here, what level this must be carried to. This will take more than just a good aim!

Cancer Man isn’t one to take insults lying down. In “Terma,” he sends an assassin to the same farm to take out the woman in charge of the Syndicate’s project to find a vaccine for the Black Oil. She is also the mistress of the Well-Manicured Man. Her work, and the secret behind it, are in danger of exposure, what with a hearing underway by a Senate Committee. But Cancer Man’s real motive is personal – to get even. He knows the Well-Manicured Man will never be able to prove he was behind the hit, but he wants to twist the knife:

WELL-MANICURED MAN: Dr. Charne-Sayre was murdered.

CANCER: By whom?

WMM: If I knew, do you think I’d be standing here talking to you?

CANCER MAN: (smiling) Oh… you need me now… A man of my capabilities… is that it?

WMM: This was a professional hit.

CANCER: And you out here all alone… so vulnerable… Were you sleeping with her? Surely you wouldn’t be so foolish as to put the project at risk for the sake of your personal pleasures.

Cancer Man’s motives are never entirely clear. Although he wants to keep the secret of the alien menace (“If people were to know the things I know, it would all fall apart.”), he doesn’t seem to be a mere quisling like the Elders who hope to survive the invasion by cooperating fully with the Colonists. Indeed, he seems to hint that he is the only man both willing and able to work against them.

There is one obvious mystery about Cancer Man that was never resolved, or even discussed much by fans: his charmed life. After Quiet Willy carries out the hit ordered by the First Elder, it seems he must be dead. As Walter Skinner reports, “no body was found but there was too much blood loss for anyone to have survived.” Again, in “Requiem,” where he is wheelchair-bound, he somehow survives being pushed down the stairs.

Cancer Man can’t be an alien hybrid himself – his goal in “Amor Fati” is to become one. We have to assume that his miraculous escapes from death are mere plot contrivances like those in soap operas. The same can be said of his son Jeffrey Spender, who in “One Son” faces seemingly certain death at the hands of his father, but somehow survives and turns up again in “William” and “The Truth.” But speaking of “One Son,” that episode ends with some cryptic dialogue:

CANCER MAN: This picture you have — I haven’t seen it since you were born. You probably don’t even know who the other man is.

SPENDER: I don’t care. Get out.

CANCER MAN: It’s Bill Mulder, Fox Mulder’s father. Isn’t that something? He was a good man… a friend of mine… who betrayed me in the end.

SPENDER: I know more than enough about your past… enough to hate you.

CANCER MAN: Your mother was right. I came here hoping otherwise. (takes out gun) Hoping that my son… might live to honor me… …like Bill Mulder’s son.

(He reluctantly aims gun and fires at Spender, then tucks gun back into his coat and leaves the office.)

Surely Cancer Man believed at this time that he was Mulder’s biological father, that Mulder and Spender were half-brothers. He had almost certainly believed that from the time they were born. What can have been the point of this little tête-à-tête, which can’t have been meant for any ears but those of a dead man walking? Perhaps only to justify to himself murdering his own son.

There is another anomaly: the decline in Cancer Man’s health after the transfusion of Mulder’s alien genes in “Amor Fati.” We know that the operation went wrong for him, and he even refers to it obliquely in “En Ami.” But why did it go wrong, if Cancer Man was so certain of his relationship with Mulder and therefore so certain of the procedure’s success? William B. Davis, in an interview in 2000 for the official X-Files website, didn’t know himself, but theorized that it might have meant he wasn’t Mulder’s father, after all:

It could be that he has become ill because the operation where he transferred brain tissue from Mulder failed. Perhaps the reason the operation failed is that CSM believed that his DNA matched Mulder`s but complications arose because the DNA does not match.

Although he tells Scully he is dying in “En Ami,” however, he is to all appearances still in good health. Yet by the time we see him again in “Requiem,” which presumably takes place only a few months later, he has become that pathetic cripple in a wheelchair – still smoking, but through a hole in his throat. More important, he has apparently been locked out of the corridors of power in Washington, where he had been a insider as late as “Biogenesis” and “Amor Fati.”

His declining health can be explained, even if the details don’t seem consistent with “cerebral inflammation.” But his loss of status is more problematical. In “En Ami,” he was using Scully to get at a Defense Advanced Research Agency scientist who thinks he has been communicating with her but whose e-mail messages on her computer have been intercepted by his own agents.

Cancer Man told Scully that Cobra had the secrets of miracle cures for all manner of diseases but, of course, it’s more likely to have been something else entirely. In any event, he used Scully as bait for Cobra, then had a sniper take him out the minute he appears. That sniper had apparently been told to kill Scully as well, but Cancer Man shot him first. Whatever Cobra knew was on a CD ROM that Cancer Man threw away – it might be a sacrificial gesture if the disk actually had any cures, including for his own illness; but then again, it might contain useless information or secrets he already knew.

What are we to make of all this? Why did he spare Scully? Did it have anything to do with her ova? She was apparently drugged during the course of the episode, while riding in a car with Cancer Man, and woke up to find herself in silk pajamas at a motel. That touched off much speculation, including about the possibility that Cancer Man was the one who got her pregnant – but Chris Carter later made it official that Mulder was the father of her child.

Cancer Man’s quixotic effort to “rebuild the project” in “Requiem” makes it almost impossible to conceive of him having any rational motive. Yet if we are to give the Devil his due, we have to entertain the possibility, however remote, that he indeed somehow engineered Scully’s pregnancy even if he didn’t father her child. That he foresaw the need for a child of Mulder’s to carry on the struggle. That, even in “The Truth,” he sought to goad Mulder rather than break him.

5. Alex Krycek

Where do you get off copping this attitude? I mean, you don’t know the first thing about me.

–Alex Krycek, in “Sleepless”

Alex Krycek was always hard to know the first thing about, let alone the last thing. Cancer Man and the Elders and their henchmen – we all knew where they were coming from. Well, we thought we did, anyway. Krycek, we hardly knew at all.

Which side was he on? His own. That’s as good a guess as any. A pure opportunist. A criminal without a cause. Ratboy, fans called him, and there was speculation that his very name came from the Czech word for “rat.” It could well be; Czech for “rat” is “krysa,” and the –ek ending is typically Czech, as in Dubcek.

When he first showed up at the F.B.I, he was evidently working for Cancer Man, as witness his role in “Duane Barry” and “Ascension,” running interference in the abduction of Scully. There’s little doubt that he was Cancer Man’s trigger man in the murder of Bill Mulder, and a partner in the attempted murder of Scully that ended up causing the death of her sister Melissa.

Where and when and how he hooked up with Cancer Man remained a mystery, as did how he managed to join the F.B.I. He was said to have been born in America to Russian émigrés, and to be fluent in Russian. That doesn’t rule out his being of Czech origin; during Cold War times, a lot of people from Soviet satellites like Czechoslovakia went to work in the Soviet Union. The Kryceks were presumably good Communists, but the de-Stalinization that began in 1956 may have shattered their faith and led them to move to the United States.

All that is pure speculation; we never actually see anything of Krycek’s family. We never knew anything of his love life, if he had one, before his bizarre relationship with Marita Covarrubias. What we mostly saw was that he was a callous killer, no matter who he works for or seemed to be working for at any given time. His known body count was fifteen, the last recorded being that of Micheal Kritschgau in “Amor Fati.”

Besides racking up a high body count, he seemed to hold a record for preternatural knowledge. Early on, he could have picked up details of the conspiracy from Cancer Man or the Elders. But how would he know that the Alien Rebels are going to attack the Elders in “One Son?” How could he know – if he really did – that the replicants wanted either Mulder or his son to die in “Existence?”

Krycek was possessed by the Black Oil in “Apocrypha,” but continued to act in character, striking a deal with Cancer Man for the location of a UFO hidden in a missile silo. Perhaps he picked up some alien secrets along the way, but any information he absorbed then would have been way out of date by the time of “One Son” and “Essence.” He had contacts in Russia, too, we learn in “Tunguska,” and knew something of the Russian vaccine program from them, but again it couldn’t have been much more.

Krycek’s basic motivation was perfectly clear, yet hard to explain. He was obviously out for himself, and his shifting alliances and allegiances have to be seen in that light. Had he not been targeted by Cancer Man and the Elders in “Paper Clip,” we can imagine, he might have continued to serve them to the end. What we can’t imagine is his off-again, on-again relationships.

In “Tunguska,” he was dragged to Siberia by Mulder because of his knowledge of Russia, but despite his Intelligence contacts there he wasn’t a happy camper. Escaping from the Russian research facility with Mulder, he ended up captured by former inmates of the same facility who cut off their right arms to keep from being taken back – they think they’re doing him a favor by cutting off his.

Despite going through all that, and previous imprisonment in the same missile silo as the UFO (The Black Oil abandons him at that point and flows into the craft.), he loses none of his amoral charm or cheekiness. “Well, look who’s answering the batphone,” he quips when he calls Syndicate headquarters and finds himself talking with the Well-Manicured Man in “Patient X.”

When he approached the Elders with the Black Oil-infected Russian boy and the Russian vaccine, he presumably wanted to get back in their good graces. But he ended up siding with the dissident Well-Manicured Man over the Alien Rebels, and – presumably at his behest – delivered a warning to Fox Mulder. Given that Kryeck was responsible for the murders of Bill Mulder and Melissa Scully, he seems a poor choice as messenger.

It was also in “Patient X” that we saw Krycek going at it hot and heavy with Marita Covarrubias, after they had pretended to be total strangers at the abductee incineration site in Kazakhstan. Yet Ratboy didn’t appear to be the least bit upset when the Elders decided to use Covarrubias as a guinea pig for the virus and the vaccine at the cost of her health and her beauty.

Why should she have had anything to do with him after that, even supposing him to have been the world’s greatest stud? Yet there they were, together again, in “Requiem.” Even though she told Krycek at first that she had been sent by Cancer Man to get him out of jail, when she would have been content to let him rot there, she ended up siding with him against her employer.

Not only that, but Cancer Man seemed to trust Krycek, even though he was at odds with him in “One Son” and “Amor Fati” – and later had him sent to prison for “trying to sell something that was mine.” Who, if anyone, was Krycek working for then? He blackmailed Skinner into sharing information about the UFO and its inscriptions, and murdered Kritschgau for his laptop with the same end in view. Why?

For that matter, what had his game been in “SR 819,” where he had infected Skinner with remote-controlled nanobots to force him to run interference again with Mulder and Scully over something to do with nanotechnology and Tunisia? He was apparently using that leverage again during the events of “Biogenesis” and “The Sixth Extinction.”

Whatever… Once he learned of Scully’s pregnancy, Krycek’s only goal seemed to be terminating the fetus – or Mulder himself. In “Deadalive,” he even tried to blackmail Skinner again – offering a vaccine for Mulder, but only if he saw to it that the unborn child died. Rather than sink to that, Skinner chose to disconnect Mulder from his life-support. John Doggett, who interrupted Skinner, tried to get hold of the vaccine himself – but Krycek destroyed it. Only, how did Krycek get hold of another vial, and would it have worked against the super soldier infection as opposed to the Black Oil?

In “Existence,” shortly before he met his end at the hands of Skinner, we saw Krycek in the company of Knowle Rohrer, who served with John Doggett in the Marines during the peacekeeping operation in Beirut in 1982 and later resurfaced as Doggett’s Deep Throat. Only Rohrer was now a super soldier, and Doggett’s growing suspicions that he had been setting him up were confirmed when the two appeared in a car together.

Rohrer was an attempt, along with the Toothpick Man, to create a new axis of evil on The X-Files, but there was never time to develop him as a character. Unlike Billy Miles and his ilk, he apparently came out of the military research project revealed in “Nothing Important Happened Today.” At least, one would expect Rohrer to have been missed if he had ever been abducted.

But it is never clear whether he is a soulless alien weapon, a quisling, or – like the Elders of the Syndicate – part of a conspiracy to buy time to deal with the aliens while keeping the coming invasion secret to avoid touching off mass panic. In “The Truth,” we get conflicting versions of the truth about the super soldiers from Doggett and Mulder – after Mulder is put on trial for killing Rohrer when we know Rohrer can’t be killed.

Of course, Rohrer had risen from the dead once again at the end of “The Truth,” as he must have at the end of “Nothing Important Happened Today.” There his object was to protect the secret of the U.S. Valor Victor, aboard which the super soldier program had been using DNA taken from unwilling and unknowing subjects – perhaps including Dana Scully. The explosion that destroyed the shipboard laboratory at the end also destroyed any chance of learning the truth about the program.

The whole business about the Valor Victor was in a sense a replay – or should that be reploy? — of the Strughold Mine business in “Paper Clip.” But the project must have been underway long before Krycek became involved with the Syndicate or the Russian vaccine project. Giving The X-Files a revisionist history thus gave Krycek – and even Cancer Man – a revisionist history. Somehow they and the Elders never had any idea that any of this was going on.

Neither, it would seem, had informants Deep Throat and X, or ambiguous figures like Marita Covarrubias and Michael Kritschgau. Fortunately, the real story of The X-Files didn’t have to stand or fall on such details.

Tune in tomorrow for Part 3

3 Comments