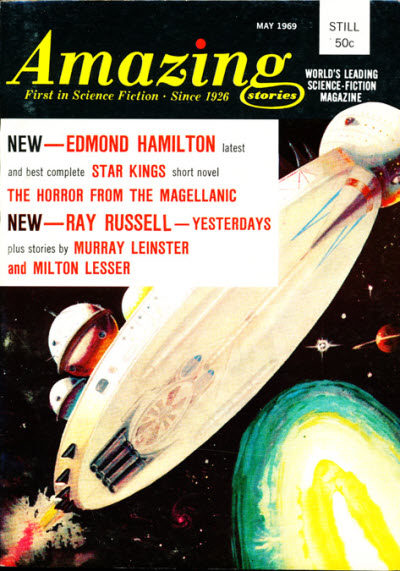

Introduction: Ted White served as Editor of both Amazing Stories and Fantastic Stories form May, 1969 until February, 1979, one of the most successful periods in both magazines’ histories. Tasked with filling a magazine with compelling fiction on a very restricted budget, Mr. White nevertheless managed to secure both influential authors and important works for both titles during the course of his editorship, and it is safe to say that without his involvement, it is unlikely that Amazing Stories would have survived to reach its 50th anniversary, let alone to now be preparing to celebrate its 100th.

The staff, fans and supporters of Amazing Stories would like to take this opportunity to personally thank him for helping to keep Amazing Stories alive.

We are equally grateful to David Langford of Ansible Editions and Mike Ashley, author of the introduction, for their support and permission for allowing us to bring these excerpts to you.

The following excerpts are drawn from the recently released Ansible Editions’ The Amazing Editorials by Ted White Published by

Ansible Editions, 94 London Road, Reading, England, RG1 5AU ae.ansible.uk and is dedicated –

To the memory of Sol Cohen, who paid me pennies,

but gave me free rein, which was priceless

Contents copyright © 1969-1979 Ted White.

Introduction copyright © 2023 Mike Ashley.

Afterword copyright © 2023 Ted White.

The Amazing Ted

Introduction by Mike Ashley

A magazine isn’t the same as a book, leastways, a very good magazine isn’t. The big difference between a good book and a good magazine is that the magazine has a personality. That personality may in part be a product of the contributors but its chiefly created by the editor – and of an editor who loves what they’re doing.

That’s what made Ted White such a good editor. He was at heart a fan – he’d won a Hugo Award as Best Fan Writer in 1968 – and a die-hard fan knows what other fans want, even if at times he has to tell them what they want. Ted was known for his fan columns both before and after his editorship of Amazing Stories and Fantastic and he never fought shy of an argument if he felt he had a valid point. He was no stranger to controversy and he could not avoid being controversial in his role as editor for publisher Sol Cohen, as some of these editorials reveal.

Not all editors could imbue their magazine with their personality, though most readers of the science fiction magazines, especially back in the 1950s and 1960s, could detect the editorial presence. It was obvious, for example, in John W. Campbell’s Analog (formerly Astounding) chiefly because of Campbell’s strong and single-minded editorials. Campbell coaxed and challenged, perhaps even bludgeoned his writers into crafting their fiction and presented his frequently controversial ideas through his editorials.

But Ted White was not that sort of editor. Campbell had no fannish roots but his passion was for channelling his writers into looking at the world in a different way and produce fiction that questioned the status quo. White’s passion was for the pure love of science fiction itself – let’s leave aside his other passions for music and comics. White had started buying sf magazines in the early 1950s and soon after he stumbled across Other Worlds Science Stories, which was edited by Raymond A. Palmer. Palmer had once been editor of Amazing Stories but in wanting to explore further his interest in UFOs and other strange phenomena he had started his highly successful magazine Fate, soon followed by Other Worlds. Unlike most previous editors of the sf magazines Palmer liked to chat to his readers. His approach was informal and welcoming, and that way he seduced you into the fold.

Robert A.W. Lowndes was similar, and his editorials and features in Science Fiction Stories – or The “Original” Science Fiction Stories as it became known to distinguish it from any impostors – and its companions Future Science Fiction and Science Fiction Quarterly, felt like you were listening to an old friend. Both Palmer and Lowndes had to face the fact that they had a low budget for their magazines, so not all stories could be top drawer, but if the readers could be enticed into feeling they were a part of the magazine and that their voice could be heard, they would keep coming back, issue after issue.

White had a similar problem. He tells you about it in these editorials, so I need not repeat too much here, but suffice it to say that when Sol Cohen bought the rights to Amazing and Fantastic from Ziff-Davis in 1965 he had to introduce drastic measures in order to keep the magazines alive. Both had been published at a loss and did not fit comfortably into Ziff-Davis’s portfolio which included such glamorous slick magazines as Modern Bride. To bring them back into profit Cohen, and his business-partner Arthur Bernhard, chose to pay as little as possible for fiction and, apart from one or two new stories per issue – if that – everything else was reprinted from the magazine archives and nothing extra was paid to the author. This brought Cohen into a clash with the Science Fiction Writers of America (SFWA) which, for a while, blacklisted both Amazing and Fantastic as markets. Such was one of the controversies into which Ted White stepped when he took over the editorship in October 1968. The debacle between Cohen and the SFWA had blighted the two previous editors of the magazines: Harry Harrison, who managed to put up with it for five months, and Barry Malzberg, who survived six months. Both had regretted taking on the editorial role almost as soon as they started and both made valiant efforts to improve the situation. This shows White’s strength of character. He survived as editor for ten years and by the March 1972 issue had succeeded in ousting all reprints – check out that issue’s editorial for the background to all of this.

White managed to make both Amazing and Fantastic presentable and enjoyable again. It’s a shame some of the letters in the letter column, “…Or So You Say”, aren’t included here because there are fascinating comments by readers on the various changes White introduced – most in favour, but not all. Some readers took White to task for airing his political views and White valiantly defended himself in his editorials. White’s editorship passed through some landmark moments, the Apollo moon-landing being the most exciting. But he was also editor at the time of Amazing’s fiftieth anniversary in April 1976. He also discusses issues such as the New Wave, and how he believed that was dividing fandom, and ecological problems and how that was dividing politics. You get a detailed view of life in science fiction during his decade as editor.

White had a powerful intuition and acumen as an editor. His first new serial, starting in the November 1969 issue, was Philip K. Dick’s “A. Lincoln, Simulacrum” (better known by its book title, We Can Build You) which had been written in 1962 but rejected by the publisher and it was not until White asked to see it that it was published. White had achieved the same in Fantastic with “Hasan” by Piers Anthony which had received a dozen rejections, but Ted White learned of it, asked to see it and published it. It gave rise to further work by Anthony in both magazines, including his novel Orn, serialized in Amazing in 1970. Orn was subsequently published by Avon Books, where the editor George Ernsberger had suggested some revisions. White had also suggested changes and Ernsberger respected White’s abilities and waited to see how his revisions affected the final copy, and he ran with that version.

White encouraged new writers, amongst them Gordon Eklund, Ian McEwan (yes, that Ian McEwan), George Alec Effinger, Thomas Monteleone and John Shirley, and he also lured F.M. Busby back into writing fifteen years after his first and only previous sale. White also brought in new artists, especially Mike Hinge, whose psychedelic covers caused some controversy. White had battled with Cohen to be able to use new artwork rather than reprints of covers bought from European sources. He turned to his contacts in the comic-book industry and ran covers by Dan Adkins, John Pederson, Jeff Jones and the first professional work by Mike Kaluta.

All this hard work paid off, to some degree. For the first time in four years Amazing Stories was nominated for the Hugo Award in 1970 and again in 1971 and 1972 – this last year along with Fantastic. Alas it never won, and when the category changed White was nominated five years in a row as Best Professional Editor. Again, he didn’t win, but it was still a significant achievement.

You get the sense of all that hard work in these editorials. The magazine’s circulation had risen slightly under White’s editorship but by 1976 it had started to fall again, and both magazines switched from bi-monthly to quarterly. The last straw was when Sol Cohen chose to retire in September 1978. Control of the magazines passed to Arthur Bernhard but though Bernhard implied he would be receptive to ideas he refused to invest any money in the magazines and even stopped paying White. White quit on 9 November 1978, the last issue under his editorship being the February 1979 Amazing. When the next issue appeared, dated May 1979, under the editorship of Elinor Mavor, hiding behind the alias Omar Gohagen, all of White’s improvements had vanished in one appalling sweep. It was all so frustrating.

White became editor of Heavy Metal, but only for a year, and in 1985 he was Editorial Director of Stardate, but for only four issues, as the publisher overextended himself and the magazine failed. It would be some years before Amazing found its feet again, and many look back on that decade under Ted White as something of a Golden Age. He demonstrated what could be achieved against overwhelming odds if you had determination, understanding, the right contacts and knowledge and, above all, that sense of loyalty and appreciation of the science fiction field. Such editors are rare and this volume and its Fantastic companion allow us a chance to remember his hard work and celebrate his achievements.

Introduction copyright © 2023 Mike Ashley. Used with permission.

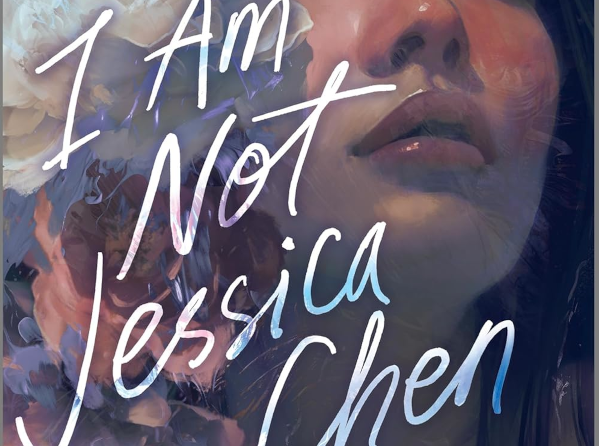

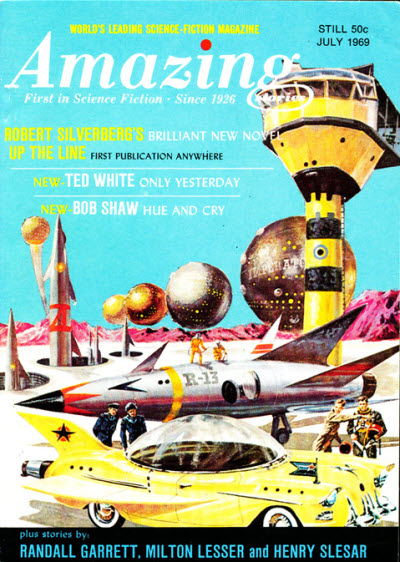

May 1969

We’ve heard a lot in recent years about the New Thing in science fiction. It’s not an isolated movement, of course. It has its parallels in the other popular arts, in the sudden flowering of rock music, for example, and in the determined exploration of electronic sound and ‘randomized music’.

But it seems to me that what we have not heard enough about is the question of our “roots.”

In rock music the spectrum is broader: the field now not only supports the acid rock of Jimi Hendrix and the instrument-smashing antics of The Who, but also the melodic freshness of the Beach Boys and the incredibly rich tapestries of Van Dyke Parks.

But what of rock’s roots? Rock music grew out of Rhythm and Blues music – the country hollers and urban laments – and rock has not forgotten its roots. The Rolling Stones made Muddy Waters fashionable again, and more recently a British group called Ten Years After has been duplicating the mid-thirties Kansas City jazz of Count Basie and Jimmy Rushing.

What has any of this to do with science fiction?

I think the parallel is apt, particularly at the points where it breaks down. For if the New Thing or New Wave of science fiction is our “acid rock,” where is our Ten Years After? Where are our roots?

It’s not enough to simply point backwards. We can reprint memorable stories of the past (and do) as easily as we can listen to a reissue of classic 1930s jazz. But what of our new writers? Must they all seek change so determinedly? One J.G. Ballard can be important – but ten little Ballards?

It has been said that the New Wave of science fiction is composed of writers less interested in telling new stories than in telling stories a new way. It has also been said that the New Wave writers are most preoccupied with new ideas, and a new relevancy in their stories to the realities which press in upon us daily.

I suspect that the apparent contradictions in the claims put forth for the New Wave lie in the fact that there is no true New Wave, in the sense of a single school of thought. Instead, there has been an explosion of ideas and ways of expressing them among a diverse group of writers – writers who often disagree with each other about their goals and desires for the field and for science fiction in general.

What has happened is an ex post facto label, “New Wave,” applied across the board to a set of writers who differ in any fashion from the old-fashioned norm. What is dangerous is that these writers are now being judged in terms of the label (most of them reject all such labels for themselves) rather than in terms of their individual output. Worse, a cult has formed, around the label, and, in a few cases, around individual writers taken to be the gurus of the label. A case in point is the aforementioned Ballard. I repeat: one Ballard has fascination; a multiplicity of Ballard imitators can only evoke boredom.

Very few of the writers lumped into the “New Wave” have ignored their roots in science fiction to the extent their admirers and fans have done. The Samuel Delanys, the Roger Zelaznys, are well grounded in the significant values and virtues of this field. But all too often novice writers seeking to emulate these men are ignoring or castigating “old-fashioned” sf as irrelevant or worse. These novice writers have fastened upon the superficialities of style in the so-called “New Wave,” and ignored its foundations. The cleverness of form distracts them. Most are unaware of the old-fashioned space-opera that underlies, for instance, so much of Delany’s work. Delany has taken classic 1945 Planet Stories plots and totally refurbished them, sometimes even turning them inside-out. But books like his Nova are crammed with the excitement and wonder of the old space-operas, simmering just barely under the surface.

It is fashionable today to decry the old action-adventure sf story. It is easy to look back upon the yellowed pages of the old pulps and find lurid examples of bad writing. But it is also possible to find a sort of primitive vigor and excitement which parallels the sort one finds in the old, raw blues music. And if there is much that was very bad in the old space-operas, it is usually less a fault of the form than of the individual author.

It is my conviction that the science fiction field needs a magazine in which the old and the new can exist side by side, each thriving from its proximity to the other. And that is what I intend for Amazing: Something of the old (the reprints) and of the new (the best of the new writers), perhaps something occasionally borrowed (many of the old ideas are worth the remining), along with the blues.

Science fiction has roots. Amazing is the world’s oldest science fiction magazine, and has the strongest roots. We intend to continue to explore them.

In this issue we do exactly that, with the fourth of Edmond Hamilton’s “Star Kings” novelettes. Next issue will begin a new, and very different, novel by Robert Silverberg, “Up the Line.” The old and the new, the past, present and future: you’ll find them all here in each issue of Amazing.

July 1969

Living as I do that life of indolent ease known to all writers and editors, I rarely rise early in the morning. But one morning late in December of 1968, I made it a point to be awake with all essential mental capacities functioning at the gawdawful hour of seven a.m., something less than three hours after I’d knocked off for the night on the book I was writing and had gone to bed.

The occasion was December 21st, and the launching of Apollo Eight. New York City skies were still streaked with rust when I nudged my wife awake, climbed out of bed long enough to turn on and tune the TV set, and then slipped back in under the warm covers.

It was a flawless launch, and a perfect omen for a flawless flight. The liftoff itself was a thing of beauty as the giant Saturn 5 rocket ignited and billowing clouds of steam (from the water used to help cool the launch pad) screened it momentarily from sight and then, poised upon its huge sun-bright torch, the Saturn climbed majestically, almost too slowly to be believed, into the Florida skies. Afterwards one television commentator remarked that the sound of the Saturn thrusters was almost enough to shatter the windows of buildings miles away. The three-inch speaker on my TV set didn’t begin to suggest that awesome sound, but it hinted, broadly. And in my mind I felt it.

The ball of fire that seemed to pursue the rocket into the sky, hungrily consuming most of its fuel in those first few minutes, was greater in diameter than the length of the rocket itself. The flames that trailed the fireball were several times longer. It was a sight I shall never forget: a demonstration of sheer raw power: the guts and determination of a nation to hurl three men and their artificial environment 240,000 miles up and to the Moon.

I’ve watched dozens of live-TV lifts-off from Cape Kennedy, and I’ve always felt a sort of primitive awe and thrill, but this one was something special. This one brought up the hair at the base of my neck, and filled my eyes with tears as I squeezed my wife’s hand. This one was the one my generation built its dreams on. This one was science fiction.

In the beginning there was a dream, and the dream was that man might some day visit the other planets in our heavens. For centuries this dream held little substance, and those planets were considered more philosophical analogues than worlds in some sense like our own, worlds on which a man might stand. Then, slowly, as we entered the scientific age, man began to dream ways we might travel across “the ether.” Early notions, such as balloon ascensions and giant cannon shots, were romantic fantasies, but in the early years of this century a few men – Opel, Goddard, Gernsback – began to believe we had a genuine means for crossing space: the rocket.

It was an era of primitive air flight, a day when horses were still vainly competing with the automobile, and you had to be a little crazy in the eyes of your fellows to believe in rockets. People did insane things with rockets, strapping them onto bicycles, motor-cars, and even railroad flat-cars, in order to test them, and in many cases these fanatic backyard inventors were maimed or killed by their backfiring experiments. And yet, in that relatively early era, a German rocket society was founded which would ultimately lend its impetus to the V-2 rocket, and independently Robert Goddard would invent a spidery contraption which in all its essentials forecast the modern, liquid-fueled rocket engine.

That same era witnessed the birth of science fiction as we know it today. Although we inherited most of the most common devices of science fiction from Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, we owe our genre to Hugo Gernsback. Gernsback was one of those backyard inventor guys, an early pioneer in radio and television, fascinated with electricity in all its forms, and determinedly forward-looking. Today we would call him a ‘futurist’. In those days he was simply one of a few brilliant visionaries.

Gernsback published magazines for those who thought as he did; the best known was The Electrical Experimenter. In that magazine he occasionally printed stories as well as articles. These stories were rather low on literary merit, but they were well received, because they centered themselves on unusual inventions, and presented new ideas in an entertaining fashion.

It was out of Gernsback’s almost Messianic zeal to popularize science and tomorrow-mindedness that Amazing Stories was conceived. The April 1926 issue of Amazing Stories was the first issue of the world’s first science fiction magazine, and out of this single seed has grown our present virile genre of books and magazines.

The phrase “science fiction” had not yet been coined, but years earlier – in 1915, to be exact – Gernsback had dubbed these science-oriented stories “scientifiction” (from which comes the still common abbreviation, “stf”). On its masthead, Gernsback called Amazing Stories “The Magazine of Scientifiction.” Below was the slogan that best explained not only Gernsback’s enthusiasm for this new genre, but his readers’ as well: “Extravagant Fiction Today… Cold Fact Tomorrow.”

Early sf readers believed that slogan with a fanaticism which rivaled Gernsback’s own. Amazing Stories was less a business enterprise than a cooperative effort between Gernsback and his readers in which everyone was united by this common bond. It was out of Amazing Stories’ letter column that science fiction fandom was formed, to grow yearly in strength until today fan conventions are routinely attracting hundreds of attendees.

“Extravagant Fiction Today… Cold Fact Tomorrow.” We believed that. We believed, with the rocket enthusiasts, in the eventuality of space travel, of journeys to the Moon and the planets. We believed in it in that special way that is impossible to explain to a newcomer today, twelve years after the dawn of the true space-age.

I can no longer be sure how far my faith goes back. I was reading science fiction at the age of eight, and I recall it excited me even then with visions of rocketships and space-travel, and that I filled pages in my school notebooks with doodlings of rockets and stars. It was inevitable that I should, early in my teens, become a science fiction fan drawn increasingly into the inner circles of “fandom.” Didn’t we all believe?

With age comes, if not maturity, sophistication and even cynicism. There’s an old joke that you can discuss anything in a science fiction fanzine except science fiction. After ten, fifteen or twenty years reading the stuff, you take so much for granted; your early sense of wonder becomes jaded. Yeah, yeah, space-travel, sure; but what’s new? My generation was not Gernsback’s pioneering generation; my generation was the one that followed. We weren’t the crusaders; we consolidated already-won gains. We didn’t invent science fiction; we only improved upon it.

But we believed. Like the generation before us, deep down inside we believed it: “Extravagant Fiction Today… Cold Fact Tomorrow.”

I was one of several writers interviewed by a reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle during the recent World Science Fiction Convention held in Berkeley across the Bay. “Science fiction is not concerned with prophecy,” I told the man tendentiously. I was reacting against all those Sunday supplement pieces in which a feature-writer adds up our box-score and decides we really haven’t predicted today’s world all that well. “We aren’t trying to predict an accurate tomorrow,” I said. “We are simply projecting possibilities, all kinds of possibilities, wildly conflicting possibilities, all those possibilities for tomorrow in which we see a good story.”

Well, that’s true enough. But when we score – when we do call the right shots – we like to brag about that too. Sure, in actual fact most of yesterday’s extravagant fiction looks just as extravagant today. Most of it was never written with any other intention. But in spirit we are realizing those extravagances as facts. So what if, in 1946, Robert A. Heinlein could still tell the story of a private, backyard flight to the Moon in his classic juvenile, Rocketship Galileo, while in point of actual fact today’s rockets cost so many millions of dollars that only the mightiest nations can afford to build them? The spirit of what Heinlein wrote more than twenty years ago (and the spirit of all those who wrote of space voyages before him) has been vindicated by the Apollo Eight mission.

As I write this, a newsmagazine lies open on my desk at my left, its pages open to a double-page spread that tugs violently at my sense of wonder every time I let myself look at it. In the foreground is a lunar landscape: low grey hills and worn-looking craters, an oddly close horizon; it looks for all the world like a skilful tabletop model, and its surface is pocked with a multitude of dimples that might have come (were it indeed only a tabletop model) from many ladies’ high heels. Beyond that close horizon, black sky; velvety black, a rich, deep black.

And in the sky – Earth. Large and looming, its upper half sunlit and jewel-bright, covered with white cloud-swirls through which gleam turquoise-blue oceans and salmon landmasses, its lower half black with the blackness of space.

A startling sight, and it’s real. This is a color photograph of the Earth, as seen from seventy miles above the surface of the Moon. This is the stuff of our dreams. This is ours, our belief, our faith made real.

This is where Amazing Stories has been pointed since its birth, for the last forty-three years. It was Hugo Gernsback’s dream and now it’s our reality.

Hugo died, in August of 1967, only a little over a year too soon. But he lived to see the initial conquest of space, and he had lived to see himself vindicated in his many personal predictions hundreds of times over. He lived long enough to see the Science Fiction World, and for him, I am sure, it all came true: the extravagant fiction of his early days is now, in the largest sense, cold fact. It was his dream that made it real.

But still we look ahead. Still we dream. Somehow reality has a way of diminishing many of our dreams. The marvels of science we imagined only yesterday are today’s electric can-openers and transistor radios, and somewhere along the line all the wonder in them has disappeared.

Today the news magazines and other mass media patronize us. They have taken our wonders and marvels away from us from us and made them mundane “news.” They speak of the Apollo mission in glowing terms, and then they contrast it with what they call “sci-fi” (a most ugly and contemptuous term for science fiction). “This is real,” they say; “not like that sci-fi stuff.”

To them our dreams will always be only dreams and nothing more. Rooted in the pedestrian realities of life as they see it, the mass media are incapable of a sense of wonder, incapable of dreaming dreams that might yet be realized in fact. Theirs is a sharp dichotomy: reality is reality and dreams are dreams. What is real was always real. What once we dreamed must always remain only a dream – and it’s best put behind us as a part of our feckless, romantic youth. And, most galling of all, when our dreams break through into reality – when we succeed in sending three men around the moon and bring them safely home – the mass media rejoice and then quickly rewrite history. They always knew we were going to do it.

Sure, they did.

The ship came down out of the heavens looking, according to a lucky Pan-American pilot who saw it, like a comet, trailing an incandescent white streamer some one hundred miles long. It had entered its 26-mile re-entry window perfectly, thus bringing about the conclusion of a mission that was for all intents and purposes flawless. The boosters and ship contained more than three-and-a-half million working parts, and performed without error. Launching was only six-tenths of a second late, the lunar orbit was just a half-mile off, and the splash-down was within three miles of the waiting carrier. It was two days after Christmas, 1968.

Col. Frank Borman – Capt. James Lovell, Jr. – Major William Anders – we salute you. Amazing Stories salutes you.

We knew you could do it.

The Apollo Eight mission was pretty exciting for me, but so is the editorship of Amazing Stories. Every science fiction fan, and almost every sf writer has spoken at length, at one time or another, on what must be just about everyone’s favorite topic of conversation: Things I Would Do If I Do If I Was Editing X Science Fiction Magazine. So have I.

There are, I think, two basic ways to edit a magazine like Amazing: it can be approached as a job and done – even enjoyed – on that level, or it can be approached as an enthusiasm, a sort of super fanzine, and edited for the love of it. Most magazines outside our field are edited by nine-to-fivers whose involvement with the products of their editorial toil is minimal. For them it is just a job, not so very different from writing advertising copy or driving a bus. But the science fiction field is a special field, a field where the dedicated amateurs have always outranked the bored professionals. Scratch one of today’s writers or editors and you’ll almost always find a former fan underneath. Perhaps it is because the sf field has never paid well, and has always demanded loving devotion from its pros; perhaps it is just that undying sense of wonder in each of us which drives us to express ourselves here, rather than elsewhere.

My approach to Amazing is, of necessity, one of love and of enthusiasm. Compared with the earnings of my books, my work on this magazine is not as well-paid; compared with the earnings of writers in other, more lucrative fields, my work in science fiction as a whole is not as well-paid. But here I am, working with others like me, simply because this is what I – and they – prefer to be doing.

In order for me to more thoroughly enjoy Amazing, I am making changes, large and small, which I hope will lead you to more thoroughly enjoy the magazine. Most of these changes are subtle: changes in tone, in emphasis, in balances. Some of them will not be immediately apparent. Some are still in the wings – I’m pretty excited about some of the projects we still have in the planning stages, and which I hope I’ll be able to tell you more about soon. But some are here now.

I’m definitely excited about the first material I’ve been able to buy for Amazing and for Fantastic, our sister magazine. Beginning in this issue, Robert Silverberg’s “Up The Line” hits me more strongly than anything I’ve ever read by him before. Maybe it’s his use of first-person narration – and the way he suggests, without aping him, Robert Heinlein’s better work. Silverberg has been writing in this field for more than a decade, but I’m convinced he’s only now beginning to hit his stride as a major science fiction writer, and a novel like “Up The Line” is going to do a lot to consolidate his new reputation for him.

Jack Vance’s “Emphyrio” in Fantastic is also a major work by a long-established writer who keeps coming up with fresh ideas and stories. There is a solidity and a depth to “Emphyrio” which, I am certain, is going to make that novel a Hugo contender this year.

We’re expanding our departments, too. Not only is the letter column back, but in this issue we revive The Club House, a column wherein many of the recent sf fanzines are examined and reviewed. In Fantastic we are launching a new department, Fantasy Fandom, wherein some of the best fanzine articles and essays are reprinted for you. This, plus expanded book reviews, and our other regular departments, is all designed to give you a better, more fully rounded magazine, a magazine which gives you more than any other. I might add that we have dispensed with guest editorials; from now on I will be using this space to talk directly to you on an editor-to-reader basis.

I’d like to hear from you – from all of you – about these changes, and what you think of them. I must ask your patience – it is going to take me a while to slip comfortably into the editorial harness – but I hope you’ll tell me when I’m doing something wrong, and, conversely, when I’m doing it right.

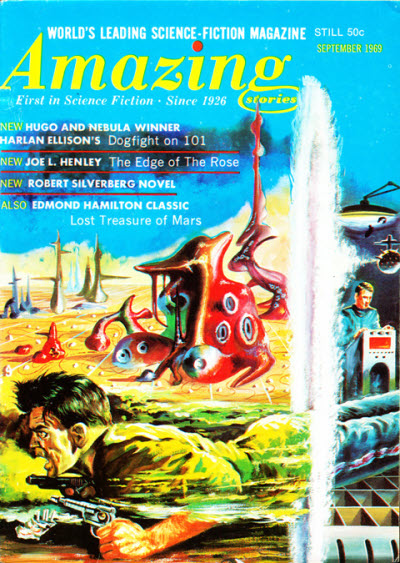

September 1969

As I write this the 1969 New York Lunacon is only a matter of hours past although by the time you read this, April 12 and 13 will be somewhat more distant memories. The Lunacon is an annual “regional” sf convention, so-called because it bases its appeal on local attendance, is held by the same sponsoring group (the New York Lunarians) each year, and is one of a growing number of smaller conferences, conclaves and conventions which aim to supplement (rather than compete with) the annual World SF Convention. (The World SF Convention will be held in St. Louis this year; for information I suggest you contact the St. Louiscon Committee, P.O. Box 3008, St. Louis, Missouri 63130.) The Lunacon began as an annual meeting on a Sunday afternoon, usually held in a small meeting hall somewhere in lower or midtown Manhattan, and attracting less than a hundred attendees. However, the last few years have witnessed the conference’s rapid growth, both in scope and attendance – from a single Sunday afternoon to a full weekend that begins with a sponsored party Friday evening, includes programs on Saturday afternoon and Sunday afternoon, and fades, finally, into quiet Sunday evening parties for those still hanging on – and from several score in attendance ten years ago to over four hundred last year, and well over six hundred this year. And this year the Lunacon, enjoyed, as it has for the past several years, the facilities of a major New York hotel.

The rapid growth of the Lunacon is not an isolated occurrence. Less than ten years ago, the average World SF Convention had less than six hundred in attendance. But the last two world conventions have both had well over a thousand attendees, and the forecast for St. Louis is that two thousand may well show up! Other regional conferences are reporting attendance figures doubling or nearly doubling over those of the past year alone.

What this seems to mean is that the microcosm we call science fiction fandom is experiencing a sudden spurt of growth on a nation-wide basis. The number of people who are interested enough in science fiction to attend a conference or convention is rapidly multiplying. New fan groups are turning up all over, many with previously independent existences and only recently aware of a larger fandom.

It would be nice to hope that these new fans reflect an overall growth in the sf readership at large – and that the financially precarious existence of most sf magazines (and many sf writers) might grow proportionately more stable. But that may only be a dream. Certainly many of these “new fans” are actually an outgrowth of Star Trek’s phenomenal popularity, and others are a result of other, “offshoot fandoms,” such as Tolkien Fandom. Others yet are primarily interested in reading and trading comic books (and ignore the program and sf orientation of these conferences) or belong to what has sometimes been most appropriately called “Monster Fandom.”

Many long-time sf fans have expressed dismay at the growing size of the conventions – even while organizers are alternately celebrating “our” increased importance and bemoaning the growing workload – and have wondered if the close-knit community feeling we once knew is certain to be lost.

I think this ties rather closely to the present contention expressed between the so-called “New Waves” and “Old Waves” of science fiction. We once felt a sense of community – and for many of us the New Wave seems to threaten it.

Science fiction has always been a fish out of water, a genre or sub-genre of fiction which has never relished its association with the other sub-genres of fiction. The early sf magazines – Amazing Stories the first among them – were not precisely “pulps”; they measured roughly 9″ x 12″, were printed on better quality paper, and had trimmed edges. Yet, they were classed as pulps, had covers nearly as lurid, and printed nothing but fiction – and a “sensationalistic” sort of fiction as well… you know that rockets-to-the-moon nonsense is filling the boy’s head with pernicious claptrap! And all too soon, as the Depression took hold and the magazines began fighting for their lives, they assumed the traditional ragged-edged pulp format as well. (Have you ever thumbed through an old pulp magazine? Have you ever tried to thumb through one? Let us all say a silent prayer for trimmed edges on our magazines.)

Once pulps among other pulps, sf magazines found themselves a part of great chains of magazines, their advertising sold by the yard to Rupture-Easer and Beauty Around The World, and I Spoke With God – Yes I Did, Actually and Literally. Even at the time I discovered the pulps – near the end of their domain – it was a commonly held belief that pulp magazines were for the semi-literates, and at least two stages in quality below comic books. A boy could buy a comic book openly; he was ashamed to be seen carrying a pulp.

We did not benefit from our exposure to this sordid literary industry. The lettercolumns of the sf pulps of the forties are full of tales of torn-off covers, hidden covers, and other signs of the paranoia which infected most of the magazines’ readers. Our proud heritage of Wells and Verne was forgotten. Our magazines portrayed bosomy babes, monstrous BEMs, and ornate rockets and rayguns on their covers – and it made no difference that their interior texts were moderately literate and well-written. People go by appearances – even us.

We sneered – sometimes unjustly – at the other pulps we found on the racks. Sports-story pulps, western pulps, mystery pulps, romance pulps, war-story pulps, masked-hero pulps – we sneered at all of them. Pulp trash, they were. We were something better. The sort of people who bought those other pulps moved their lips when they read; we had broad mental horizons and fine minds. (Never you mind that many of the same authors wrote for all the pulps, including many respected names in sf.)

It gave us a sense of community. We sheltered together for sustenance. We needed it. Here we were, believers in space travel when space travel was arrant nonsense, warners of atomic doom when the atomic bomb was something we were holding over the heads of those Godless commies – “What? You read that crazy Buck Rogers stuff?” was the usual reaction we met when we confessed the truth.

So we told ourselves that we were the Prophets of Tomorrow. That we knew better. That our innings would come, some day. We repeated, ad nauseam, the story of how the FBI visited Cleve Cartmill after a too-convincing story was published describing an atom bomb, in the early forties. And when Sputnik I went up, we cheered. Total vindication!

– Maybe.

A lot of sf magazines died in the late fifties. A lot more had died in the early and middle fifties. What went wrong?

The pulp magazines died in 1955. The handwriting had been on the wall for six years. Street & Smith, the oldest publisher of pulp magazines (they’d started with “dime novels”), killed its remaining line of pulps in 1949. And that was the second year of widespread, network television.

The other publishers held on, even while covertly establishing other, more viable, enterprises, like lines of paperback books. A few began trimming the edges on their pulps. But I can recall a local drugstore in the town where I grew up condensed its display shelf of pulps from five feet displayed with only the spines showing, to less than a foot, the cover of the topmost showing, in less than a year. The demise of the pulp was that fast.

The man who moved his lips while he read was now watching television, his feet propped up on another chair and a cold beer near his hand. And his lips weren’t moving any more.

We survived that. We survived the collapse of an entire industry. Less than a handful of mystery pulps and one – yes, one! – western magazine made it with us, through the transition into the present “digest-size” (named after Reader’s Digest, the first to popularize that size) format. There was an abortive attempt to carry the revolution one step further and into the “vestpocket” format of Quick and its host of imitators, but that fad died quickly.

But then, the sf magazine had never really been a pulp. We had always been a field apart, a fish out of water. Even when our magazines were printed on pulp presses along with thirty other titles, edited by the same man who edited all those other pulps, illustrated by the same men, and even written by many of the same writers, we were unique. We were not pulp.

Maybe we should have been. The best in pulp writing never intruded far into our field. Men like John D. MacDonald looked us over, wrote for us when it was worth while, and moved on. That’s a shame, because as MacDonald’s The Girl, The Gold Watch and Everything proves, his is a talent we could all profit from. And many others, like William Campbell Gault, Lester Dent, and Louis L’Amour, proved pulp writing was not, per se, bad writing. So many science fiction writers have been amateur writers, in both the best and worst senses of that word. Never forced to live solely by their writing skills as were pulp writers (many sf writers are strictly part-time, spare-time writers), the amateurs who dominate our field have often neglected their skills as writers. (Many, it shames me to say, have not even learned the rudiments of writing.) Yet, the sf writer has a love for his field and a dedication to it which is all but unique. (It will come as a shock to some sf fans and readers, but there are western and mystery writers who feel this same affection for their chosen fields.)

This love of the field has been another outgrowth of our small-community feeling towards sf. Many present-day sf writers and editors are former fans. Even those who were never a part of active sf fandom have a long history of special fondness for sf. We know each other. Literally. Each convention brings together many familiar faces, renews many friendships, and sometimes reunites two old friends who’ve not seen each other for one or two decades.

Add it all up: The special ghetto within the pulp ghetto, the sense of future-mindedness, the amateur dedication of both fans and professionals, the paranoia and the honest sense of special pride. These things, and more, are what the Old Wave of sf represents. These are intangibles which have little to do with the actual nature of a story, but which are summoned up in unconscious support of a Tradition.

And now the community, that little, close-knit ethnic community, is being exploded by sudden population-growth, by apparent block-busting tactics – and a sense of Tradition is suddenly transmuted into a wave of Reactionaryism.

Just what is happening?

For years some of our best people have cried out for release from the specific confines of the ghetto. It wasn’t that they necessarily wanted to go elsewhere, but that they didn’t want to feel penned up in here. Some of them were crying out for Critical Acceptance, when in actuality they wanted Higher Pay Rates. Some lusted after mundane Status – they were tired of being patronized by the Establishment critics. Others simply wanted to see their work judged as writing, and wanted neither the special pleading of some sf-oriented reviewers nor the cold shoulder of outside critics and readers.

It is very understandable. I recall the day I called upon an editor at one New York publishing house. No enemy of sf, he had been responsible for a considerable sf program by his publisher, and he had been quite willing to see me even though I was not at that time at all well known as a writer.

His secretary showed me into his office and he looked up and waved me to a seat, cupping the phone in his hand and explaining that he’d be with me in a minute. It was a small office. It was impossible for me not to hear his end of the conversation. He was talking with his boss, and they were discussing a book he wanted to buy. As became quickly apparent, it was not a work of science fiction. “I think we should bid up to sixty thousand,” he said. “We need that book. I’d put up ten thousand out of my pocket for that book.” I imagine his offer was hyperbole, but I was impressed by the sums named.

The conversation over, he cradled the phone and turned to me. We chatted a bit, and then the subject of the book I had submitted to him came up. “I like it,” he said, “and I want to buy it.” Then he explained that inasmuch as I was a relative unknown and the book was my first for his company, he could offer only $1250.00 for it. I had expected $1500.00, but I swallowed my pride and accepted his offer. I’d written books for less.

As I left that office, my pleasure in selling my book was strangely tempered by the knowledge that the going market price, then, for a science fiction novel, was about $1500.00 (an advance against royalties, to be sure, but royalties were unlikely to exceed that sum for years after the book went on sale) – while a ‘mainstream” work might fetch a bid of $60,000.00! And that was not an unreasonably high bid for the period (the book in question was the memoirs of a doctor; it never hit the bestseller lists).

I don’t imagine my experience has been unique. At that moment I felt very sharply the boundaries of my ghetto.

The Movement started in England. English sf has never been as closely tied to the pulps as has been American sf – England still remembers Wells. But I find it curious that while British writers such as John Christopher managed to crack the ghetto (with serial sales to The Saturday Evening Post and the like) years ago, the primary energizer has been a young man who found his start working for a succession of sleazy publishers doing such things as writing new blurbs and dialogue for reprinted comic strips, and writing enormous volumes of what would once have constituted pulp fiction over here. Perhaps Michael Moorcock felt the bonds of his ghetto more sharply than anyone else. Perhaps, having worked in a literary cellar for so long he was more eager than most for the sight of daylight. Certainly the guru of the British New Wave, J.G. Ballard, has never done less than His Own Thing – even in the late fifties, for the old-guard New Worlds magazine, before there was any New Wave to speak of.

I have very little sympathy for most of what passes for the New Wave fiction currently being published in Britain, but considerable sympathy for the motives which seem to produce it.

At the Lunacon just over (perhaps you wondered what the connection was, after all this time?), two program items were Impolite Interviews of Tom Disch and Norman Spinrad, conducted by Terry Carr, who quoted them their bad reviews and then allowed them to defend themselves.

I was far more impressed by their statements of aims and purposes than I have been by anything I have read by either of them. And each, I think, was speaking for the New Wave in much of what he said.

I don’t have a transcript handy, but the gist of their remarks, each given separately, was that each wanted to write stories which were free to conform to or to violate the conventional boundaries of science fiction, depending solely upon the specific direction of the story.

Both men have good classical educations in literature, and neither seems to feel any particular desire to isolate himself from the entire broad spectrum of literature in favor of a special set of “sf” conventions. When influences were named, sf writers were conspicuously unmentioned. Each remains attracted to sf for the freedom it offers to speculate about things and situations and people which are not of the here and now – but each insists upon his right to write a story which follows its own dictates, even if it departs from our own boundaries.

I fully sympathize. These men are approaching their writing as a serious artistic expression. They don’t want meaningless rockets or rayguns thrust willynilly into their stories.

I think the implications of this attitude towards writing sf are scaring a lot of those of us who still live on the old block, in the old tight-little-community. These crazy kids don’t know their place! I dunno about art, but I know what I like, and I like what I know! Etc.

The result has been the recent publication of a series of tracts against the New Wave – one author of which has a similar sort of tract in our letter section this issue – and the Choosing of Sides between Old Wavers and New which distresses me, particularly since I have friends on both sides.

I have myself taken stands in the past against much which I do not like in the so-called New Wave – mostly in articles for fan publications. For the record: A great deal of the “experimental” work published (particularly in Britain) strikes me as unsuccessful and abortive. I think that some New Wave authors are inept as writers – rather like “action painters” who cannot draw representationally and never bothered to learn – and that many are poor craftsmen whose contempt for old standards masks an inability to master the old skills. A number of writers championed by the New Wave strike me as reptilian in both their stories and their actual in-person personalities. And I once remarked that I had no use for those stories written by writers who themselves hold humanity in contempt and loathing. Finally, I regard much of the noise currently being made about the New Wave as a packaging phenomenon – a way of calling attention to and promoting specific authors, books, or products. In this respect, it is the work of editors and critics much more than of the authors themselves, most of whom have little in common and reject the New Wave label.

However, this also must be said: Most of the Old Wave is ill-written garbage. We remember fondly the stories we read in our first year or two of exposure to science fiction because it was a time when we had few critical standards, all the ideas (no matter how old) seemed new and fresh, and our Sense of Wonder was in full bloom. This is in a sense an imprinting process and it often blinds us to the faults that lie in those stories we still recall with nostalgia. The bulk of the writing in science fiction is sub-par. It compares poorly even with the bulk of the writing in those other literary ghettos-like mysteries and westerns. The best writers we can boast as products of our field do not compare well as writers with the best the other genres have produced – we have never had a Hammett or a Chandler, nor even a Ross Santee – and none of our writers can stand comparison with the true giants of literature. I am continually distressed when as an editor I am shown the works of major names in our field, writers who are published regularly in the best magazines of our field – and I find their stories full of elementary errors of spelling and grammar and often in violation of the most Old Wavish rules of story construction. Put plainly, many of the Old Masters in our field are frauds. They have gotten by on nostalgia, on the substitution of Grandiose Ideas for such elementals as Plot and Characterization, and they have become Old Masters less by talent and skill than by longevity, continued exposure, and the fact that in our small pond, a frog needn’t be too big to stand out. Too many of our Dedicated Amateurs are “amateur” in the wrong sense of the word. And one wonders if their fear of the New Wave and of the opening up of their community isn’t really just a fear that now they will have to stand before the world naked, deprived of their special pleadings and special criteria, judged as writers among other writers and nothing more. How many know they are essentially failures, but offer the excuse that “an inside crowd” is “hogging the awards,” the attention, the kudos, etc. to excuse themselves?

No, what this field needs, either to continue as a field or to be absorbed into the mainstream, is more honest writers willing to stand on their own two feet and be judged as writers and nothing more. The Wave of the banner under which they stand is not important. The critical salvos fired over their heads by opposing camps are not important. What is important is that these writers write and come forth to present their wares.

We will be the judge. You and me. The readers and the editors, but ultimately you, the readers. When a man writes a story we like, I will buy it, and you will buy it from me. When a man tells an honest story and tells it well, we’ll know him for what he is. And when another man shucks us, slips over a shoddy piece of goods on us, we’ll discover that too. He may be twenty years old or sixty years old, and he may consider himself Old Hat or New Wave, but that won’t be a consideration. We’ll judge the story.

I’d like to close right there, on that resounding declaration, but I must deflate my own sails a bit. The stories you find here in Amazing must of necessity reflect my taste as an editor, and the tastes I believe you, as readers, to possess. This is a matter of grim economic necessity – we have no Arts Council grants here. Moreover, these stories must represent the stories submitted to me, and, to an extent, those passed on to me by earlier editors. Each step of the way, you see, imposes an additional limitation. We publish the best we can get, but that is not always the Very Best. I will not apologize for any specific story in this magazine. If I didn’t think it warranted publication, it wouldn’t be here. But obviously I will like some better than others. And you may like those others better.

I want to hear from you. I want to know how the magazine strikes you. I’d like your reaction to everything in it – from the editorials and reviews to the stories and the letters. I’ve been rather boldly experimenting in these last two issues, and I shall continue, but I need the feedback of your honest response. This is not a magazine edited to suit my private whims – it is a commercial product offered in the public marketplace. We want to make it the best magazine we can – within our necessary limitations – so that it best satisfies you. We obviously can’t satisfy everyone, but we hope to satisfy more of you each issue.

So there it is: tell me what you think.

From The Amazing Editorials by Ted White, Ansible Editions, Reading, England, 2023. Contents copyright © 1969-1979 Ted White. Introduction copyright © 2023 Mike Ashley. Afterword copyright © 2023 Ted White. Reprinted with permission.

Both The Amazing Editorials and The Fantastic Editorials are available in paperback and electronic editions and can be ordered from Ansible Editions

Steve Davidson is the publisher of Amazing Stories.

Steve has been a passionate fan of science fiction since the mid-60s, before he even knew what it was called.