(This is a guest editorial. The views expressed by the author are not necessarily those of Amazing Stories magazine.)

The title of this piece might need some explaining, as it seems that awareness of the situation behind it fades without constant reminders.

A couple of years back, it was revealed that Disney had failed to pay royalties due multiple authors because the corporation unilaterally decided that copyright laws didn’t apply to them. Basically, they failed to pay royalties for works that they’d acquired the rights to through various corporate buyouts. Disney recognized that the ownership rights transferred to them with the purchase, but somehow tried to make the argument that the obligation(s) to pay royalties on sales DID NOT transfer to them.

SFWA and several other author organizations banded together and started a campaign – Disney Must Pay – and to this day, we are still hearing about authors having to settle with Disney for less than is owed them and of authors who still have not been properly compensated.

This is sort of ironic when you consider that SFWA itself has apparently decided not to take any action in another situation where authors might have been owed royalties but have not been receiving them for years for entirely different reasons.

I previously brought this situation to SFWA’s attention. I am presuming that it represents a can of something that they’d rather not be opened since I TWICE attempted to lay this situation out where it belongs, with the organization that is supposed to represent AUTHOR interests. I’m hoping that they’ve not gotten back to me through oversite rather than hoping that the issue will go away, as the latter suggests that the organization might be favoring publishers instead of authors, and that would not be a fun story to tell.

Here’s the issue in a nutshell: Periodicals – magazine issues – are being sold like anthologies, but are compensating authors like they are periodicals, which is unfair to authors.

This is no doubt a legacy of the transition to and inclusion of electronic publications and it is easy to see how this has gotten overlooked, especially in light of the fact that periodicals are not doing all that well (at least in the SF/F field) and addressing this issue would subject them to even more economic pressure, but quite frankly, authors have been getting the short end of the stick almost from the beginnin, and they’re the ones that really need the help.

This is no doubt a legacy of the transition to and inclusion of electronic publications and it is easy to see how this has gotten overlooked, especially in light of the fact that periodicals are not doing all that well (at least in the SF/F field) and addressing this issue would subject them to even more economic pressure, but quite frankly, authors have been getting the short end of the stick almost from the beginnin, and they’re the ones that really need the help.

Pay rates and “formats”, if you will, used to be different for anthologies and magazine periodicals because there USED TO BE a fundamental difference between the ways in which those different types of publications were marketed and distributed.

Periodicals used to have a shelf life, or an availability, of anywhere from two weeks to three months, depending upon the publication’s production schedule. The important element here is that following that period of time, the publication, including the contents within that publication, were no longer available for purchase by the general public (with the possible exception of a limited number of back issues that might or might not be made available at some unspecified time).

Periodicals used to have a shelf life, or an availability, of anywhere from two weeks to three months, depending upon the publication’s production schedule. The important element here is that following that period of time, the publication, including the contents within that publication, were no longer available for purchase by the general public (with the possible exception of a limited number of back issues that might or might not be made available at some unspecified time).

Periodicals paid a fee for the rights to publish the story for a LIMITED TIME FRAME. In some cases as little as a quarter of a cent per word, and, still, to this day, as low as half a cent a word (though SFWA qualifying rates*** are now 8 cents per word) and some publications pay more than the minimum..

Authors were willing to accept such comparatively low rates based on the concept that they would be able to re-sell the story after the rights they’d sold had expired; they could re-sell a story any number of times into perpetuity, usually for even lower “reprint” rates, but the amounts are not important to the distinction here. The concept built into this arrangement was that the publisher’s rights to a piece of fiction would age out in some reasonable fashion, and that anyone else who wanted that story would either have to purchase other rights to do so, or needed to hunt for used back issues of the magazine or other reprint publication.

Authors were willing to accept such comparatively low rates based on the concept that they would be able to re-sell the story after the rights they’d sold had expired; they could re-sell a story any number of times into perpetuity, usually for even lower “reprint” rates, but the amounts are not important to the distinction here. The concept built into this arrangement was that the publisher’s rights to a piece of fiction would age out in some reasonable fashion, and that anyone else who wanted that story would either have to purchase other rights to do so, or needed to hunt for used back issues of the magazine or other reprint publication.

On the other hand, anthologies (the nearest equivalent to a fiction magazine in traditional book form) would go on sale at bookstores and elsewhere, and had no expiration date. If the title sold well, the publisher would keep the title in print. Authors of stories sold to anthologies usually did so for some kind of an advance against sales and then received a pro-rated royalty amount, typically based on a percentage of 50% of the royalties, split between the various authors in the anthology, either a flat percentage (10 stories each getting 5%) or a percentage based on word count (story A is 25% of the words so receives 25% of the 50%, etc), because the editor of the anthology typically split the royalties with the authors**.

In other words, so long as the anthology remained in print and selling, every quarter, the author(s) would receive some payment, so long as the advance had earned out, and would continue to do so so long as the anthology remains in print. (Earning out an advance means that sales have been enough to cover the advance payments.)

In other words, so long as the anthology remained in print and selling, every quarter, the author(s) would receive some payment, so long as the advance had earned out, and would continue to do so so long as the anthology remains in print. (Earning out an advance means that sales have been enough to cover the advance payments.)

Here’s the problem.

Electronic issues of periodicals no longer “age out” or get removed from the newsstands. They persist, just like anthologies that the publisher has decided to keep in print (electronically).

Electronic issues of periodicals no longer “age out” or get removed from the newsstands. They persist, just like anthologies that the publisher has decided to keep in print (electronically).

Print also, now that “Print-on-Demand” is an option; publisher’s no longer have to pay a printer and then stockpile thousands of copies of an issue. They can publish their magazine issue electronically and then tick a checkbox with any number of online outlets that will happily upcharge the consumer who wants to purchase a print edition. None of this benefits the author.

If there is no aging out, there is no underlying reason to not pay royalties. If the issue is on sale and remains on sale, it is acting just like a traditionally published anthology, NOT like a PERIODICAL.

If there is no aging out, there is no underlying reason to not pay royalties. If the issue is on sale and remains on sale, it is acting just like a traditionally published anthology, NOT like a PERIODICAL.

Make no mistake. Amazing Stories paid its authors in similar fashion. It was looking into rates for electronic publications that brought this situation to my attention. The transition to electronic publishing has altered the landscape in any manner of different ways, some of which we’re just discovering now. By way of example, I had to educate NBC/Universal in the fact that in the age of streaming, their standard definition of “Re-Run” no longer applied, and my contract with them had to be altered owing to the fact that unlike pre-streaming times when a re-run was a specific event at a specific place and time, with streaming, a “re-run” could take place multiple times in the same place (someone downloads a show episode, then downloads it again. Is that one re-run of the episode or two? If it’s in the same market, does it count or not…etc., etc.)

The landscape has changed dramatically, but the methods by which authors are compensated has not followed suit.

The landscape has changed dramatically, but the methods by which authors are compensated has not followed suit.

In point of fact, the current circumstance with the periodical publications in the field is that while the publishers technically have the right to do what they are doing, it’s not “right” by the authors, just as Sol Cohen’s legal reprinting of the Amazing Stories inventory wasn’t “right”. But SFWA jumped on that one. They need to jump on this one too.

My suggestion for correcting this situation would offer periodical publishers one of two options: either continue to pay the way they have been (acquiring limited rights for a flat fee) and then removing the issue from public availability after a set period of time (30 days for a monthly, 90 days for a quarterly), except for a negotiated number of “back issues” (I’d suggest a small percentage of their paid for circulation as a way to set that number), OR

My suggestion for correcting this situation would offer periodical publishers one of two options: either continue to pay the way they have been (acquiring limited rights for a flat fee) and then removing the issue from public availability after a set period of time (30 days for a monthly, 90 days for a quarterly), except for a negotiated number of “back issues” (I’d suggest a small percentage of their paid for circulation as a way to set that number), OR

start paying advances and royalties for as long as an issue of a “periodical” remains commercially available.

A more complicated solution would be for a periodical to pay like a periodical until the issue aged out, after which it would pay a set quarterly fee, until such time as the issue was no longer commercially available. This solution is admittedly more complicated, but it does have the virtue of handling the situation exactly as it is on the ground: paying periodical rates for a periodical and then switching to royalties once the magazine issue “becomes” an anthology.

I urge SFWA to publicly state that it is addressing this issue; it could have handled this less publicly if it had been willing to address the issue both times I’d quietly raised it before, but this has stretched on for almost two years now, and it’s time to say and do something about it.

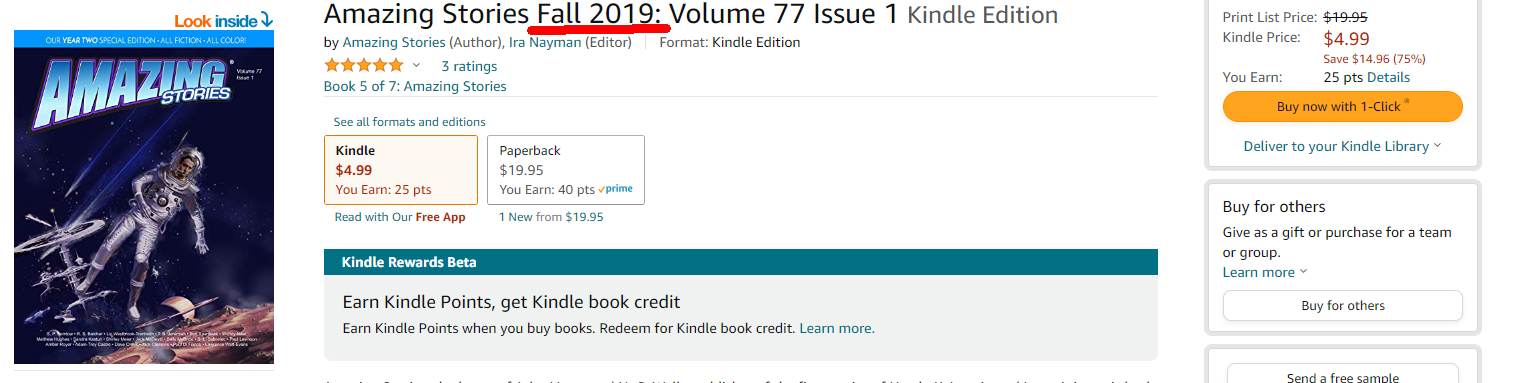

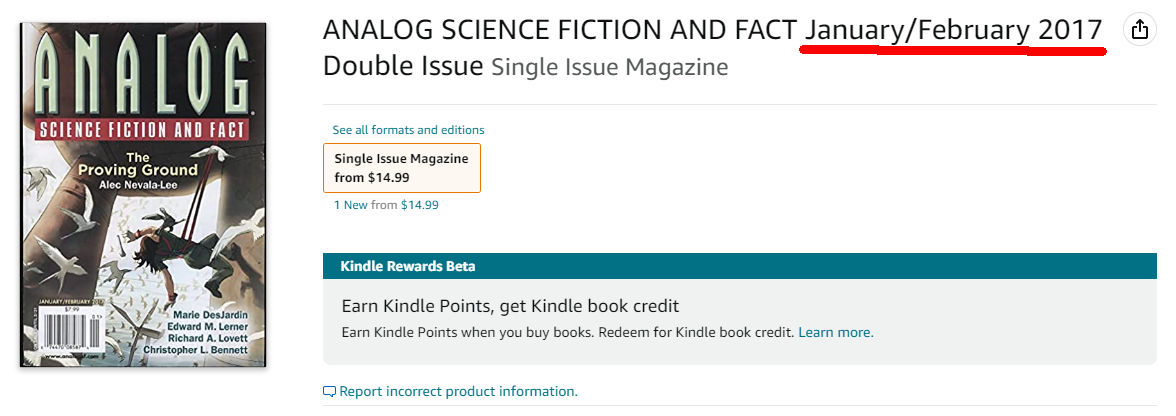

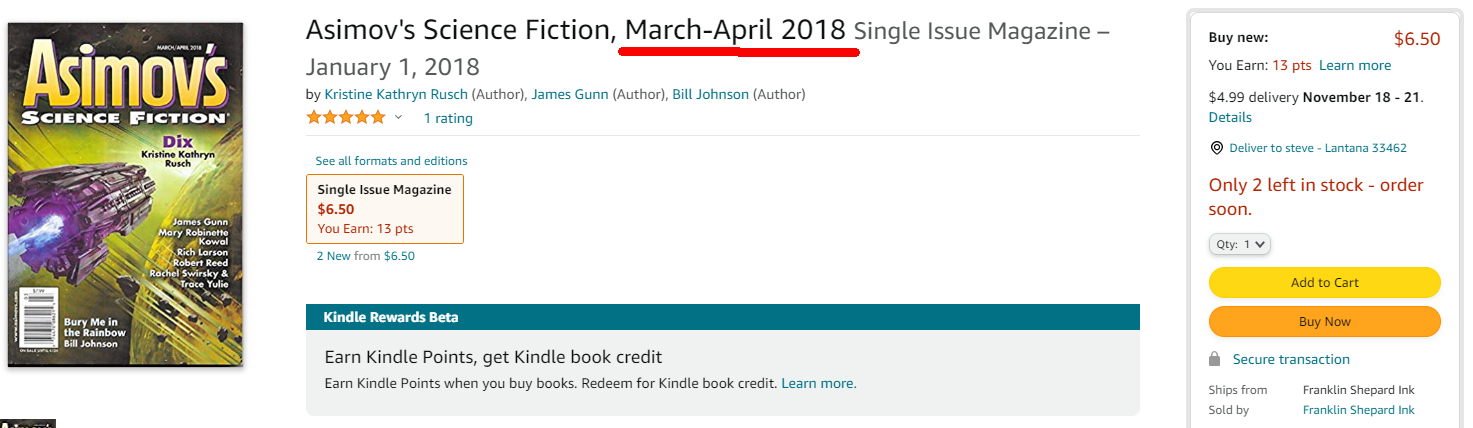

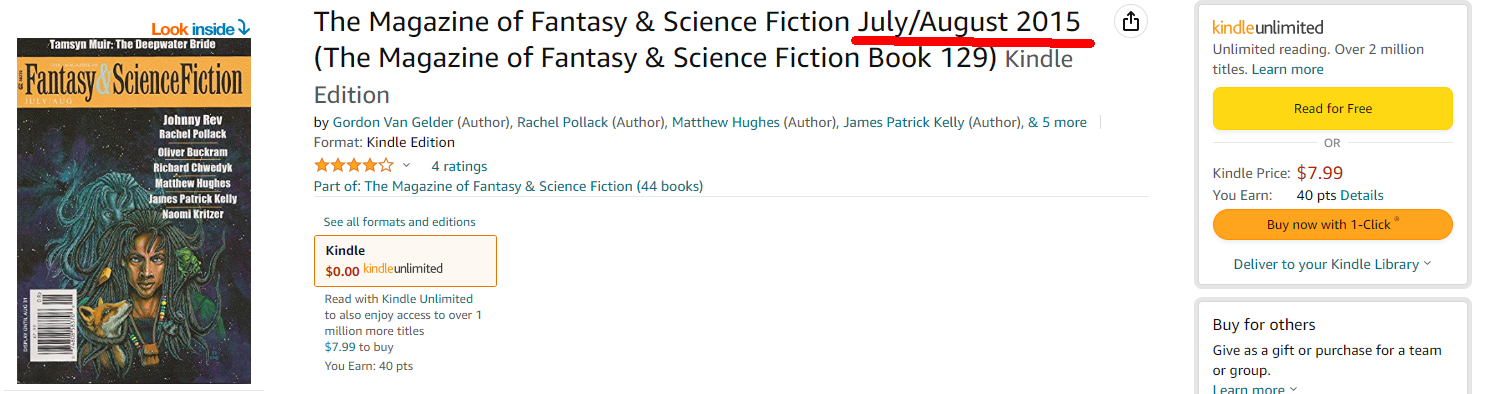

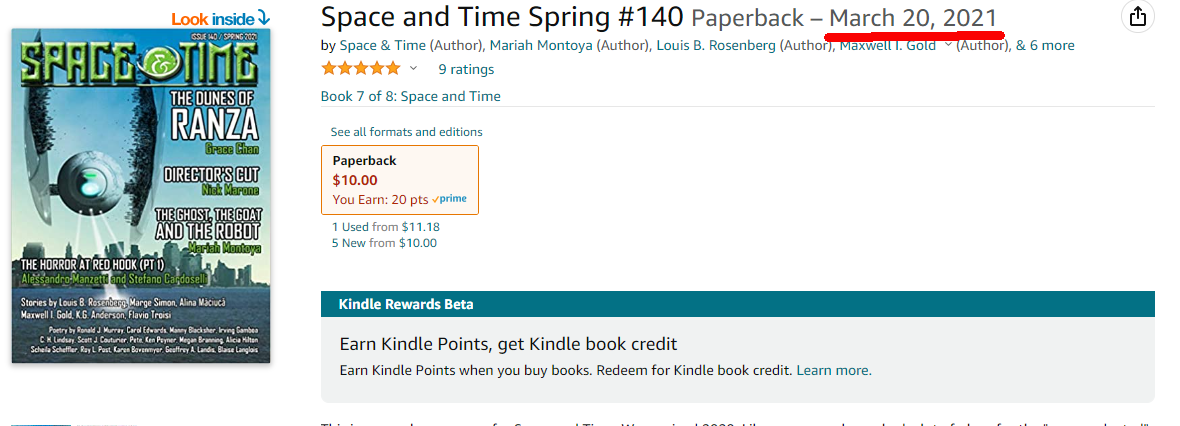

A final note: The sales of various issues of the different publications depicted here are not sales of “used” single copies, which would be legitimate under the First Sale Doctrine. These are issues being sold, as “new”, by the original publisher.

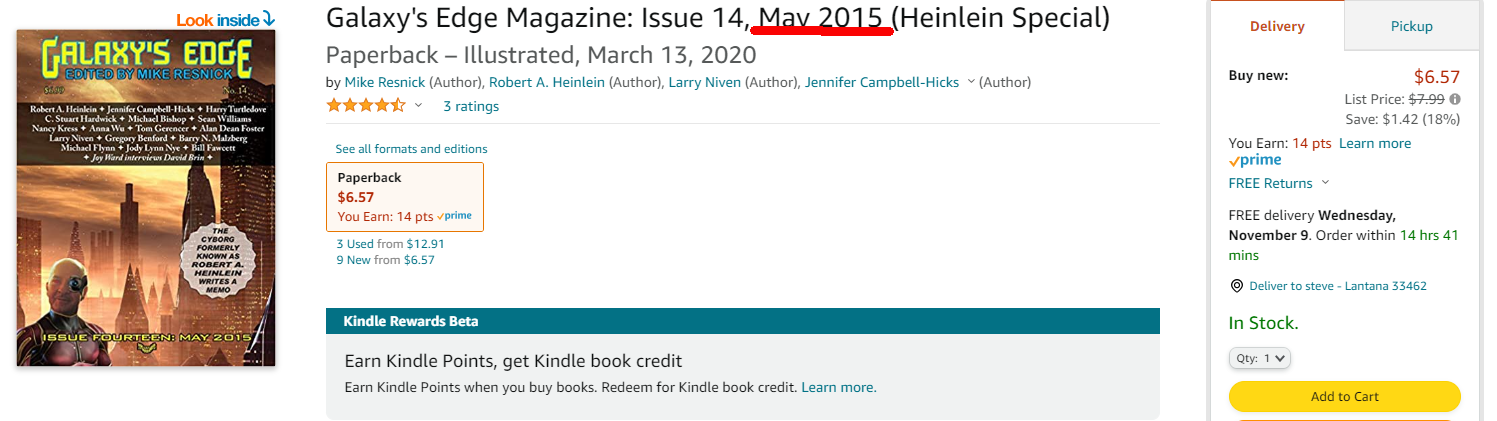

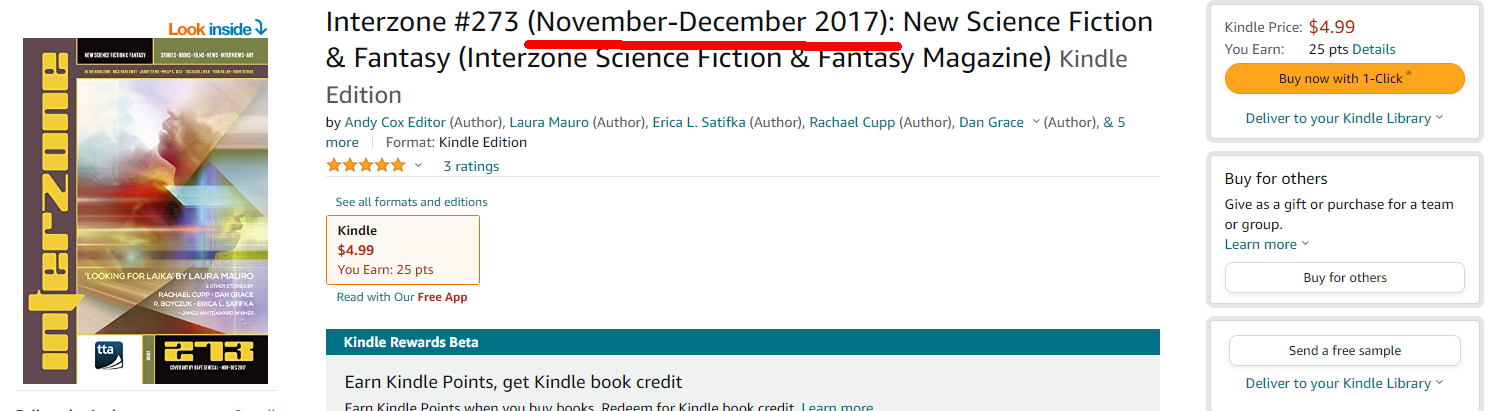

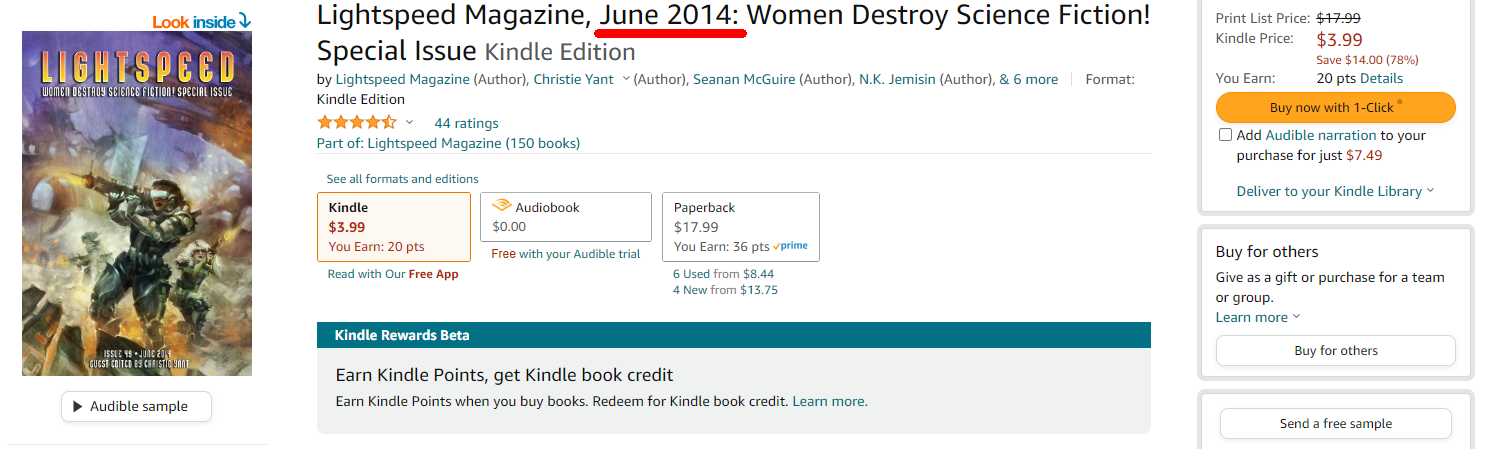

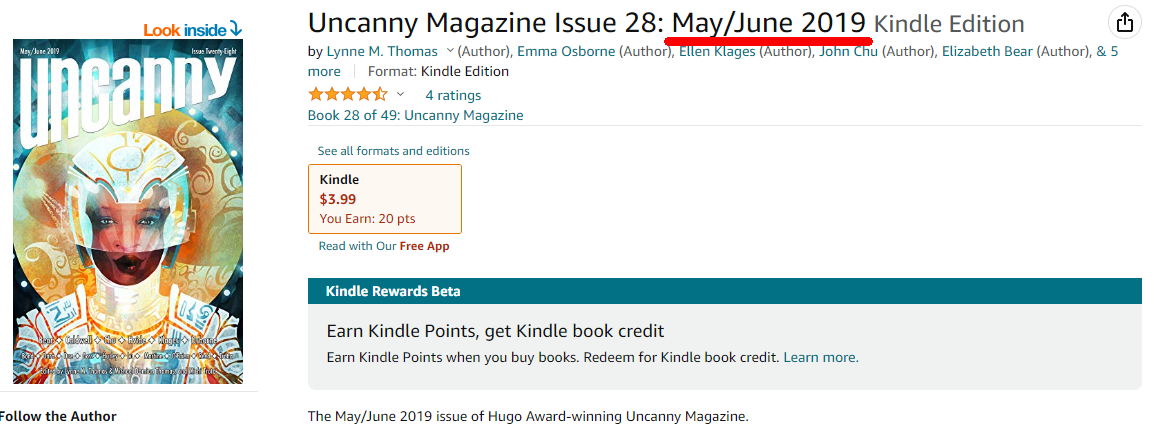

*All of the screen captures were taken in early November of 2022. Issues depicted were chosen by doing a search for the publication’s name on Amazon. The cover date is highlighted. The costs are current. Images are for illustrative purposes only, and clearly demonstrate that periodical issues a year or older are still being sold at their standard rates.

** Anthology deals have also changed over the years, with some offering flat rate or even just copies of the publication to authors, but the standard deal, preferred by most and recommended by most is for the anthology to pay an advance, often minor, and then pay royalties based on sales as previously described.

***Also in the olden days, the “SFWA Qualifying Rate” was a minimum word rate a publication must pay for the work(s) they published to count towards a SFWA member’s qualification for membership in that organization. That, too, has been obviated to some degree because the organization now only asks for certain minimum author earnings during a set period of time, which somewhat undermines the organization’s ability to enforce anything on periodicals…but that is discussion for another time.