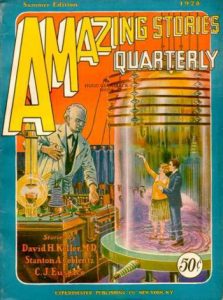

A young couple stand together, clad in 1920s fashions, the woman waving cheerfully. They are surrounded by a large glass tube, which is itself wired to a vast electrical apparatus, adorned with all manner of tubes and valves. Operating the device is a white-jacketed scientist who is completely out of proportion with the couple inside the tube, towering over them as he operates a lever. It was summer 1928, and Amazing Stories Quarterly had reached its third instalment.

A young couple stand together, clad in 1920s fashions, the woman waving cheerfully. They are surrounded by a large glass tube, which is itself wired to a vast electrical apparatus, adorned with all manner of tubes and valves. Operating the device is a white-jacketed scientist who is completely out of proportion with the couple inside the tube, towering over them as he operates a lever. It was summer 1928, and Amazing Stories Quarterly had reached its third instalment.

Hugo Gernsback’s editorial for the issue is headed “$50.00 for a Letter”, and as this title suggests, it deals with a cash prize for correspondence:

The editors realize that, this being your publication, you, the reader, have certain ideas, not only about this publication, but about scientifiction as well. Accordingly the publishers will pay $50.00 for the best editorial written by one of its readers, to be published in subsequent issues of Amazing Stories Quarterly.

With that in mind, Gernsback puts out a call for “inspiring or educational letters, embodying material which can be used as an editorial along scientifiction themes.” As it happens, there is plenty of inspiration for readers’ editorials in this very issue – which, as a fair warning, contains some rather long stories, necessitating a rather long post…

The Sunken World by Stanton A. Coblentz

In 1918 the United States Navy launched a new submarine, the X-III, which subsequently sank without a trace, taking its entire 39-man crew with it. Then, years after the war ended, a bearded man appeared in Washington purporting to be a survivor of the vessel, Anson Harkness, and proceeded to tell a tale…

In 1918 the United States Navy launched a new submarine, the X-III, which subsequently sank without a trace, taking its entire 39-man crew with it. Then, years after the war ended, a bearded man appeared in Washington purporting to be a survivor of the vessel, Anson Harkness, and proceeded to tell a tale…

Harkness’ account begins with the submarine getting sucked into a whirlpool, after which the crew are confronted with the columns, arches and temples of a submerged city:

Was this but a mirage? we asked ourselves. Or were these the remains of some submerged, ancient town? Never had we heard of mirages beneath the sea—but if this were a dead city, then why these vivid lights? And, certainly, no living city could be imagined in these profound watery abysses.

Despite initial appearances, it turns out that Atlantis is still thriving thanks to a glass dome that protects it from the sea, and the visitors encounter the locals: “their slender, graceful forms and blond features, their amiable blue eyes and rippling, unbound hair, their loose-hanging, light-tinted robes, variously colored from buff and lilac to azure and pale rose, gave them the appearance less of human beings than of walking butterflies or flowers.”

Being educated in classical Greek, Harkness is able to read the literature of Atlantis; he also receives help from Aelios, “that woman of the Madonna features and magnetic large blue eyes”. The books he studies include scientific texts on “intra-atomic engineering” and the creation of artificial sunlight, the history of Atlantis after its fall, and even a work by Homer called Telegonus, unknown to the surface world. Atlantis, it turns out, was a land of vast technological sophistication even during ancient times:

“From the beginning, our science was a strangely lopsided growth; it was most developed on the purely material side; and while it could tell us how to compute a comet’s weight and enabled us to communicate with the people of Mars, still on the whole it was concerned with such practical questions as how to produce food artificially or how to utilize new sources of energy. And in these directions it was amazingly efficient. We had long passed the stage, for example, when we needed to rely upon steam, gasoline or electricity to run our motors or to carry us over the ground or through the air; we had mastered the life-secret of matter itself, and by means of the energy within the atoms could produce power equal to that of a tornado or of a volcanic eruption.”

Initially an isolated society, Atlantis came to use its technology for warlike purposes as its people “began to swoop down occasionally upon a foreign cast, picking a quarrel with the people and finding some excuse for smiting thousands dead.” Then, however, a visionary leader named Agripides decided that Atlantis “was burning away its energies with profligate abandon, and would soon droop withering and exhausted into permanent decay” as “its best human material was being used up and cast aside like so much straw; its best social energies were being diverted into wasteful and even poisonous channels; its too-rapid scientific progress was imposing a wrenching strain upon the civilized mind and institutions.” Agripides put into action a drastic solution:

“He declared, in a word, that Atlantis was not sufficiently isolated and enisled; that it would never be safe while exposed to the tides of commerce and worldly affairs; that the only rational course was for it first to destroy whatever was noxious within itself, and then to prevent further contamination by walling itself off completely from the rest of the planet. And since no sea however wide and no fortress however strong would be efficacious in warding off the hordes of mankind, the one possible plan would be to go where no men could follow; to seal Atlantis up hermetically in an airtight case—in other words, to sink the whole island to the bottom of the sea!”

While its roots are ostensibly in ancient Greece, the novel’s Atlantis is also informed by contemporary communist thought. Harkness learns that the undersea city “is neither a monarchy, an oligarchy, nor a republic. It is a Commonality, which means that all things are possessed in common by the people and all activities shared among them.” In this society, “all Atlanteans, old and young, ill and healthy, were cared for by the State, so that no man was weighed down with- dependents”. The Atlanteans have abolished private property beyond clothes, books and ornaments, with the State housing and feeding the populace. Spiritual matters are likewise very different to what Harkness is used to:

While its roots are ostensibly in ancient Greece, the novel’s Atlantis is also informed by contemporary communist thought. Harkness learns that the undersea city “is neither a monarchy, an oligarchy, nor a republic. It is a Commonality, which means that all things are possessed in common by the people and all activities shared among them.” In this society, “all Atlanteans, old and young, ill and healthy, were cared for by the State, so that no man was weighed down with- dependents”. The Atlanteans have abolished private property beyond clothes, books and ornaments, with the State housing and feeding the populace. Spiritual matters are likewise very different to what Harkness is used to:

[R]eligion in the organized sense had ceased to exist, for the reason that each man was expected to arrive at his own philosophy… the temples that littered the country were without theological meaning, but were sanctuaries of beauty whereto any one might come at any time to worship amid the solitude of his own thoughts.

To this undersea land, the surface people seem like throwbacks to an unenlightened past. Harkness and his crewmembers first get into trouble for hunting and eating sea life – an affront to the vegetarian Atlantis. He pleads that he and his cohorts are from a different world with different standards; this wins the surface people tolerance, but not necessarily understanding. When Harkness describes New York to them, the locals are bewildered and horrified by the idea of a city where great art is deemed less important than the existence of buildings tall enough to house a million people in a single square mile. The Atlanteans are still more dismayed to learn that Harkness is a military man:

But it was when describing my own career that I was most grievously misunderstood. Had I confessed to murder, the people could not have been more shocked than when I mentioned that I was one of the crew of a ship commissioned to ram and destroy other ships; and I felt that my prestige was ruined beyond repair when I stated that I had entered the war voluntarily. Even the most friendly hearers seemed to draw unconsciously away from me after my recital; loathing and disgust showed plainly in their faces, as though I had announced myself to be an African cannibal or a Polynesian head hunter.

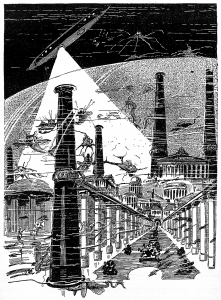

Like many attempts to imagine future societies from this period, The Sunken World incorporates eugenics into its worldbuilding. In one chapter Aelios takes the visitors to the local theatre (which is wholly subsidised by the state: “Fancy being charged for beauty or ecstasy or dreams! Why, one would as soon think of paying for the air one breathes or the light that shines upon one!”). There, they witness a high-tech play depicting Atlantis as it existed before being submerged: a grey dystopia where ugly, animalistic men toil away at vast machines in a city of colourless skyscrapers not unlike New York – all of which is swept away in the flood, the Morlock-like men presumably being killed. After the submergence, eugenics became state policy:

“According to Milares, a great social philosopher of the second century A. S., the most important of public questions is that of parentage. He maintained that the parents of each generation might either poison or uplift the next; and all of his numerous pamphlets and books bore the warning that persons congenitally deficient in mind or physique should not be permitted to breed, while those of the higher physical and intellectual qualities should be encouraged.

“In pursuance of these views, Milares proposed a basic innovation in social customs; he recommended that the institution of marriage be dissevered from that of parenthood. In other words, while marriage —and likewise divorce—should be permitted to all that desired it, parenthood should become a subject of drastic state regulation: any young couple wishing children must have their fitness examined by a carefully selected State board.”

People who fail to meet the board’s criteria are deemed “weaklings”:

“[T]he man whose contributions show no particular skill or individuality is regarded as a weakling, no matter what his pursuit. Naturally, he is not condemned so long as he does his best; but he is not regarded as a fit subject for marriage except with another weakling—and, needless to say, weaklings are not permitted to propagate.”

This process, Harkness is told, accounts for the Atlanteans’ physical beauty, widespread intellectual and artistic genius, and average lifespan of 120 years. Meanwhile, the “sickly and stunted in body”, the “imbecilic, weak-minded or insane” have been “entirely eliminated”. Harkness is impressed (“I had no choice except to admit that the results were marvelous”) although given the Atlanteans’ disdain for military pursuit, he wonders if he might be considered a weakling in this pacifistic land.

This process, Harkness is told, accounts for the Atlanteans’ physical beauty, widespread intellectual and artistic genius, and average lifespan of 120 years. Meanwhile, the “sickly and stunted in body”, the “imbecilic, weak-minded or insane” have been “entirely eliminated”. Harkness is impressed (“I had no choice except to admit that the results were marvelous”) although given the Atlanteans’ disdain for military pursuit, he wonders if he might be considered a weakling in this pacifistic land.

While much of the novel is designed to simply outline the workings of an imaginary society, it also has a narrative about Harkness and his crew’s attempts to fit in. They decide to put together an organisation for themselves, considering various titles — “The Woodrow Wilson Club,” “The Theodore Roosevelt Club,” “The U. S. A. Club,” “The X-III Club,” “The Underseas Association” — before settling upon “The Upper World Club”. The Atlantean state terms Harkness sufficiently mature for employment, and assigns him a job: Official Historian of the Upper World. But he commits a faux pas when he asks for monetary payment, yet another concept long since abolished by Atlantis:

“There is no money; there is no medium of exchange. You do your work, and in return receive all the necessaries of life; your meals are brought to you by State employees, just as they have been brought to you thus far; you are also lodged by the State, clothed by the State, educated by the State; the State works of art are at your disposal, you are admitted freely to all State entertainments, and are even granted periodic vacations to break the monotony of existence.”

As part of his initiation into the workforce, Harkness is taken on a tour where he encounters such wonders as an artificial alternative to sunlight, for agriculture; a city of glass; an atomic-powered water distillery; and a plant that renews Atlantis’ oxygen supply. Atlantis is designed to the utmost of aesthetics: farmhouses look like palaces, factories are hidden inside hillsides so as to preserve the view, and workers are “housed in dwellings not less imposing than the most stately city homes.”

Before long, Harkness becomes embroiled in the politics of Atlantis. Since its submergence, the government has been run by the Party of Submergence; but there are other active parties, including the Industrial Reform Party (“which contends that all machines and in particular intra-atomic engines are incongruous in Atlantis and should be reduced to a minimum far below the present number”) the Party of Artistic Emancipation (“which is really literary rather than political, and appeals for freedom in art”) and the Party of Birth Extension (“which maintains that the government should relax its restrictions on population”). But the smallest party is the one most vital to the plot:

“And, finally, enlarging the principles of the Birth Extension Party, there is the Party of Emergence, which is the smallest of them all and has always been highly unpopular if not actually despised, since it holds that we should renounce the principles of Agripides, enter into communication with the upper world, and send our excess population to live above seas. […] Its members have always been looked down upon as anti-social agitators, for they have transgressed against that fundamental principle, ‘Atlantis for the Atlanteans.’ Few self-respecting citizens have ever lent them support, and they have never been powerful enough to carry any of their proposals.”

“Too bad,” I found myself remarking.

When he is given lodgings, Harkness ends up neighbour to an Emergence Party member named Xanocles. The party, Xanocles explains, hopes to circumvent Atlantean population control (which limits the total number of citizens to five hundred thousand) by spreading into the surface world. This is partly “to insure life for thousands of our unborn sons and daughters, and to remake the upper world by an infiltration of our superior blood and standards” and partly to re-introduce adventure to the Atlanteans:

Everything here is so well designed that there is little chance for daring courage, the unknown—little chance for sheer primitive rashness and hardihood. Our games and recreations, our art, our political contests, of course consume much of our surplus energy; but, after all, we are the children of savage ancestors, and among our young there is a craving for keener experience. And so we of the Emergence Party favor the increase of population, so that those who wish may enjoy the greatest adventure of all—may launch their vessels toward unknown worlds!”

Harkness finds this a noble goal, and considers joining the party. Then disaster strikes when a crack appears in the protective wall surrounding Atlantis, possibly as a result of having been hit by Harkness’ submarine:

“The glass wall has been cracked!”

“The glass wall cracked?” I cried, stupidly, stunned by the terror of the words.

“Yes, the glass wall has been cracked,” the Captain affirmed, in a more matter-of-fact manner.

Although the crack is fixed, this close call with destruction makes the Atlanteans ponder their existence. The Party of Emergence starts to appear more credible to the public, and Harkness joins Xanocles in speaking in its favour. Harkness’ attempts to extoll the virtues of the upper world (including refrigerators, office blocks and condensed milk) to not convince the Atlanteans, but a rousing speech from Xanocles manages to win them over.

Although the crack is fixed, this close call with destruction makes the Atlanteans ponder their existence. The Party of Emergence starts to appear more credible to the public, and Harkness joins Xanocles in speaking in its favour. Harkness’ attempts to extoll the virtues of the upper world (including refrigerators, office blocks and condensed milk) to not convince the Atlanteans, but a rousing speech from Xanocles manages to win them over.

Atlantis decides to hold a referendum on whether citizens should be allowed to leave for the surface. To Harkness’ dismay, the result of the referendum is anti-emergence, in large part because of Harkness himself: his book on the history of the upper world, which he had been working on during his two years in Atlantis, convinced the locals that the surface is a barbaric world of bloodshed and strife. On the more positive side, Harkness marries his sometime tutor Aelios and is impressed by the brevity of the ceremony (“we were not insulted with any attempt to sanctify proceedings with words of antique witchcraft, nor humiliated by any implication that our own feelings would not amply solemnize the day”).

Alas, the crack re-appears and Harkness is sent in a submarine to enlist the help of the surface world. He arrives on the surface with a few Atlantean comrades (including Aelios) who are all thought to be mad, but eventually he succeeds in convincing the public of Atlantis’ plight. He is too late, however: when he and Aelios return in their submarine to the undersea city, Atlantis is flooded, the only life being the fish that swim between buildings.

The first published novel by Stanton A. Coblentz, and one that would be periodically republished over following decades, The Sunken World an interesting piece of work that strikes a reasonably good balance between exploring social science and delivering an engaging adventure story. Its vision of a eugenic-communist utopia is not exactly convincing, but the satirical elements ensure that the novel does not have to convince. It is never entirely clear how much Coblenz considers his Atlantis a viable utopia, and how much he considers it an idea that may seem nice on paper but will simply never happen.

“Out of the Sub-Universe” by R. F. Starzl

Professor Halley has made use of “the newly discovered cosmic ray, which has a wave-length infinitely shorter than any other known kind of light” to shrink objects and even animals, reducing matter in volume and mass without altering its form. He has been able to shrink objects and even animals to microscopic size, and now – reluctantly – prepares to send two human volunteers into this uncharted sub-universe: his assistant Hale McLaren and daughter Shirley:

Professor Halley has made use of “the newly discovered cosmic ray, which has a wave-length infinitely shorter than any other known kind of light” to shrink objects and even animals, reducing matter in volume and mass without altering its form. He has been able to shrink objects and even animals to microscopic size, and now – reluctantly – prepares to send two human volunteers into this uncharted sub-universe: his assistant Hale McLaren and daughter Shirley:

As the professor continued to adjust the controls, the bell gradually filled with a deep violet light that swayed and swirled tenuously like the drapes of an aurora borealis. The light swirled around the man and the girl, at times almost hiding them from view.

It gradually concentrated, toward the bottom of the bell, seeming to cling to the green base, intertwining the two living forms until it almost hid them from view. Yet they continued to smile and wave encouragement.

After the two travellers shrink away from view, Halley attempts to bring them back again. Instead, he ends up enlarging hundreds of once-microscopic people clad in short, filmy robes; so many that only by leaving each one at a few inches tall is he able to fit them all into his laboratory. They introduce themselves as denizens of Elektron, and reveal that – in their tiny world – millions of years have passed since Hale and Shirley departed; the pair became the Adam and Eve of a microscopic race, whose faith in the eventual intervention of Professor Halley became the core of a religion. The story ends on a wry note, with the Professor narrowly avoiding murder charges over Hale and Shirley’s disappearances before helping immigration authorities to deal with the influx of tiny Elektronites.

The latest of Amazing’s periodic ventures into microscopic worlds (past examples include Fitz-James O’Brien’s “The Diamond Lens”, Ray Cummings’ “Around the Universe” and G. Peyton Wetenbaker’s “The Man from the Atom”) “Out of the Sub-Universe” is a short but competent variation structured around a humorous twist ending.

“Ten Days to Live” by C. J. Eustace

Narrator Gaspard meets up with an inventor friend, Edward Eden, to witness the demonstration of a new machine: a small, box-like contraption with four knobs resembling radio valves and a round contraption like a mirror. “As soon as it begins to revolve,” says Eden, “this large silver bar begins to disintegrate and in so doing a stupendous power will be projected towards the sun.” The device is small but it will have a big impact, as Gaspard and Eden’s mutual friend Villiers is the first to grasp:

Narrator Gaspard meets up with an inventor friend, Edward Eden, to witness the demonstration of a new machine: a small, box-like contraption with four knobs resembling radio valves and a round contraption like a mirror. “As soon as it begins to revolve,” says Eden, “this large silver bar begins to disintegrate and in so doing a stupendous power will be projected towards the sun.” The device is small but it will have a big impact, as Gaspard and Eden’s mutual friend Villiers is the first to grasp:

“My God, do you mean—” he gasped hoarsely, “do you mean to swing the earth off its orbit?”

“Ah, thank God you have grasped it!” said Eden, and even as I gazed at him in horror, I realized that research had turned his brain, and that we were in the presence of a madman. “Yes, I shall swing the earth off its orbit. By means of my indirected beam-disintegration waves, and of a process embodied in this little machine, by which it can send waves constantly towards the sun even after it has set, just as radio waves are hurled through the ether, I intend to bring this earth several million miles nearer the sun.

“As soon as I set this framework in motion our atmosphere will at once begin to become warmer. Our climate will become more bracing, more rarefied. A luxurious vegetation will grow up everywhere. The evolution, of every man, woman and child in the world will be affected. It will alter the ways of what we have come to know as nature. It may even change the length of our days and nights. It will certainly shorten our years. We shall feel years younger. Our frames will become electrified in the buoyancy of a new atmosphere.”

Of course, the invention has a lot of potential to go seriously wrong, and so Eden makes his friends promise to destroy the machine should anything prevent him from operating it correctly.

Sure enough, something does happen to Eden: he is killed by a local man named Greely (“a degenerate who frequented the village inns… a huge broadshouldered giant, with an evil and bestial countenance”) who steals the machine and puts it into operation. Gaspard is forced to watch as waves crash and the sky darkens hours early, as Earth’s orbit is disrupted. The two scientists – religious Gaspard and atheist Villiers – debate the implications of this:

“Well, Gaspard old friend,” his voice came to me weirdly out of the gloom, “we’ve done our best for tonight. It looks as though it may be up to this Deity of yours to save the world after all. I wonder how people will take it.”

I turned on him sharply, for he was getting on my nerves.

“God will be merciful,” I said. “Villiers, this catastrophe will fetch more people back to religion than all the preaching that has ever been done.”

“Superstitious fear, eh?” he mocked. “I think that I, at any rate, shall die with a stiff upper lip.”

And I was such a coward myself that I did not doubt him. Afterwards I had cause to ponder his words.

The apocalypse continues, making it clear that humanity has only days left unless the machine is de-activated. Gaspard marries Eden’s sister, Phillipa; the scientists travel to London to meet the Prime Minister and debate how to inform the public of its impending demise; and Villiers, seeing acts of noble self-sacrifice as the world collapses into chaos, sheds his cynicism and converts to Gaspard’s way of thinking. Then, when all seems lost, Gaspard finds the missing machine (it turns out to have been hidden up a tree) and, after a scuffle with the insane Greely, the machine is destroyed and the world saved.

“Ten Days to Live” suffers from clumsy construction, with the beginning and end each relying on a ludicrous invention and an unconvincing villain. But the middle of the story, with its portrayal of an impending apocalypse and the conflicting values of the main characters, shows merit. A typical scene has the characters discuss how they intend to spend Earth’s final days:

“If I had only ten days more in which to live,” echoed the great astronomer with a subtle smile, “I think I should go to my observatory and watch this catastrophe approaching. I should take notes as long as I could in the hope that, should the end miraculously be averted, there would be some sort of authentic record to remind people that the spirit of science is unconquerable.” Brave words, I thought to myself, and I wondered if he really believed that he might have to live up to them within the next few days.

“And you, Mr. Villiers?” asked the Premier. I saw the old sardonic smile creep over Villiers’ features.

“I think I should endeavor to die as I live,” he said after a minute’s reflection. “To me, the most interesting study in the world is the observation of people. I should like to watch their reactions to this news, and get the results down on paper as a record, even as Sir Philip says—for our successors.”

“I think that your reactions would both be abnormal, gentlemen,” said the Premier. “Might I be permitted to ask this lady her opinion?” he added, bowing to Phillipa.

The poor girl went as white as a sheet, and my heart went out to her. But she kept her hands folded on her lap, and when she spoke her voice was quite firm.

“If what we all dread is really going to happen, I think I want to go to a secluded place somewhere—to a place where I could pray for all the unhappy souls my brother’s folly has condemned. If it were possible for me to offer myself as some sort of sacrifice, I would do—be—“

Her voice broke, and she buried her face in her hands. We all stirred uneasily.

“The Menace” by David H. Keller

“The Menace” is quite possibly the single most bizarre work published in Amazing Stories thus far. Structured as four parts, all sharing a regular set of characters but each standing as a self-contained adventure, it feels as though a long-form serialised narrative has been mashed together into a single story with no discernible sense of construction. The subject matter, meanwhile, is even weirder than the presentation…

“The Menace” is quite possibly the single most bizarre work published in Amazing Stories thus far. Structured as four parts, all sharing a regular set of characters but each standing as a self-contained adventure, it feels as though a long-form serialised narrative has been mashed together into a single story with no discernible sense of construction. The subject matter, meanwhile, is even weirder than the presentation…

The first chapter is “The Menace” proper, which opens with a mystery. On three occasions since the past year, the New York police have taken fingerprints of white criminals, and found them to be identical with filed prints belonging to black people. At first, the police wondered if this was a flaw in their method of fingerprinting, but they soon found that something stranger was happening: the individuals in question were black people who had altered their appearances so as to pass as white.

Concurrently, wealthy individuals unknown are moving to New York, purchasing large amounts of real estate, and inviting black people to move in. As a result, the black population of Greater New York has gone up by five hundred per cent. Biddle a prominent banker, outlines the phenomenon:

“From all over the United States, Central America and Europe, in fact wherever there are members of that race, they are steadily moving to New York, and in some way they are helped to make a living. Each day it becomes harder for a white man to secure work here, and every month a larger percent of the work in the city is being done by colored labor. That does not mean just pick and shovel work. They are going into the so-called white collar positions, and the white men are forced to either associate with them or to leave the city.”

Who is responsible? New York authorities have sent detectives to solve this mystery, but they have all gone missing. And so, the task falls upon Taine, a well-travelled and multilingual detective from San Francisco. He is given the mission to work out what is going on — by disguising himself as a rich black man from French Indo-China.

Operating under the name of Jules Gerome, Taine becomes recognised across Harlem as a wealthy batchelor. He even wins the heart of Florabella Acquoine, daughter of a mixed-race banking president. He speaks to the girl’s father, who reveals all: five years ago a group of black people found a source of gold, and became the richest people in the world, capable of buying New York. However, they still needed to overcome racial prejudice; but then along came a brilliant physicist who showed them a means of making them appear white. The group later “changed the color of a selected number of brilliantly educated, capable colored men and women”, but this was just the beginning of the plan: “When the time comes, every negro in the world, irrespective of his brains, will be turned white.”

At the request of the detective, Mr. Acquoine obtains permission from the “Powerful Ones” to turn himself and his family – including prospective son-in-law Taine – white, “not just pretended white, but actually white.”

Taine is able to further win the favour of the Powerful Ones through generous monetary donations (“I am sure that nothing but the most deadly hatred of the white race could have impelled you to take such an important step”). Infiltrating their circle, he learns about the origin of the colour-changing process, which turns out to be a serum that removes skin pigmentation.

But the game is soon up. Taine is exposed, and ends up standing before “a well formed, rather beautiful woman” with “jet black” skin (“Why should I want to be white—when I hate them so?” she asks) and a diamond-encrusted coronet. She announces herself as the high priestess of the Powerful Ones: “All great organizations, Mr. Taine, must have a religion to hold their units together… we decided that some type of Voodoo worship would appeal most to our followers.” She explains that they worship a serpent-god, and in his honour will give Taine to a gigantic boa constrictor named Ourebouras.

“Your race can change the color of their skins but they cannot change the color of their souls” declares Taine. “No matter how white they may become, they will always remain black inside. When the tom-tom sounded a while ago these white men of education and refinement and wealth swayed in their chairs and inside them their souls fell at your feet to worship you and your snake. I have seen that sort of thing on the Congo. A sea of white-wash cannot change you. The race was made black and will stay black.”

In another twist, it turns out that this is a ruse on the part of the priestess, who was known as Ebony Kate prior to joining the secret society. In reality she doesn’t want to kill Taine; instead, she is in love with him, and wants to give him a drug to make him permanently black (“I’se want a man which has a white man’s mind and a black man’s skin”). After a struggle, Taine sets off an explosion which destroys the building and kills over a thousand members of the conspiracy – pausing, but not halting, their schemes.

The second chapter, “The Gold Ship”, is set a year later. It opens with the French government making a bold proposal, offering to pay off its wartime debts to the United States – along with debts owed by the other allied countries and Germany – with over four billion dollars’ worth of gold. The US government is perturbed: where did this money come from, and can the country accept it without inspiring the envy of other nations?

The second chapter, “The Gold Ship”, is set a year later. It opens with the French government making a bold proposal, offering to pay off its wartime debts to the United States – along with debts owed by the other allied countries and Germany – with over four billion dollars’ worth of gold. The US government is perturbed: where did this money come from, and can the country accept it without inspiring the envy of other nations?

The job of solving the mystery again falls upon Taine. Speaking to the President, the detective brings up the Powerful Ones and the possible source of their wealth. Taine gathers that the source is somehow associated with the sea – is it possible that the criminals extracted gold from sea water through electrolysis? A professor of chemistry joins the discussion, comparing this process to alchemy:

“Now you are talking about something interesting,” replied the old man, in a sprightly tone. “When you go into alchemy you turn an everyday chemist into a dreamer of dreams. For thousands of years chemists have been trying to do just that. Dr. Dee and Edward Kelly described the exact process in thirteen steps. Athotas the Mysterious was always able to supply his needs and taught the art of making gold to his pupil and friend Cagliostro. They either made the gold or were able to cause others to believe they made it. The arguments pro and con are difficult—it is not a question of chemistry. It goes into metaphysics and philosophy.”

The professor describes working alongside a young man who “seemed to be of a rather extraordinary intelligence for a negro” and, before being discharged for stealing material, was attempting to create gold: “I think his idea was that if he could only divide the atom into electrons and protons and then put enough of these together in the right proportion, he could make gold.” The President sums up the findings of the meeting:

“There is a gold ship, but it does not take the gold out of the ocean. It is simply a floating laboratory and the chemist is no doubt the negro who was discharged for stealing from the Professor. He is one of this group of criminal negroes and he supplied the gold they were going to buy New York with. Failing in their plans to turn the negroes in America white, he and his confederates have in some way induced the European nations to let them pay the debt. Perhaps they asked for social equality in return. But I doubt England’s willingness to grant that. They will pay the debt, in gold, and then they will combine and make some other metal, like platinum, the standard. They will refuse to trade with us unless we accept the same standard, which will ruin us commercially. Our gold will be valueless and it will take us years, maybe centuries, before we could resume our place in the world.”

Aboard the ship are Count Sebastian, a surviving Powerful One; and his wife-to-be Angeline Pleasance, a mixed-race woman who naturally passes as white (“My father was French, an adventurer, while my mother was a Malay. Of course they are considered Caucasians, but three generations back there was colored blood in my father’s family and no matter how you look at it, I am not a white woman.”) Taine is sent by the president to sink the vessel – but only too late the authorities learn that there are innocent French women aboard alongside the various criminals.

Fortunately, Taine is able to scupper the plan without sinking the ship. Instead, he has the ship bombarded with x-rays, which successfully destroy the crooks’ synthetic gold. He is aided in his mission by Angeline, who is in reality a male agent in disguise (“the best female impersonator in the world”).

In the third chapter, “The Tainted Flood”, Count Sebastian and the other Powerful Ones develop an inversion of their first scheme: they plan to spike the New York water supply with a chemical that will turn white people black. If the plan succeeds, the only remaining whites “will be the poor people, the crackers and the red necks and the white trash” who “won’t hesitate to shoot any black man who might bring the disease to their isolated mountain homes.”

In the third chapter, “The Tainted Flood”, Count Sebastian and the other Powerful Ones develop an inversion of their first scheme: they plan to spike the New York water supply with a chemical that will turn white people black. If the plan succeeds, the only remaining whites “will be the poor people, the crackers and the red necks and the white trash” who “won’t hesitate to shoot any black man who might bring the disease to their isolated mountain homes.”

Taine overhears these schemes, and hopes to see the authorities fight against the plot “till the mangled bodies of the conspirators were burning harmlessly on the ground, owned forever more by the Caucasian race.” The detective eventually manages to procure a sample of the drug, and takes it before the authorities of New York. However, the powers that be are unconvinced of his story, and desire a test subject.

They consider using a man on death row, but are concerned that he might leak the story; meanwhile, using a mentally handicapped person would pose ethical issues. Finally, one of the authority figures expresses belief in Taine’s story, and after scorning the others (“For thousands of years you have thought that a white skin meant a white God. Tonight you do not even dare to turn some white idiots black”) volunteers to test the drug himself. Lo and behold, he turns black before the assembled observers. The race-changer is hailed as a hero (“He has sacrificed something that is dearer than life for the sake of his city”) while Taine orders work to begin on an antidote.

Then we come to the fourth and final chapter, “The Insane Avalanche”. The three remaining leaders of The Powerful Ones – Count Sebastian, Marcus and Dr. Semon – remain “banded together for the total subjection, and, if necessary, destruction of the Caucasian race” despite the failure of their schemes thus far. They find a new ally in psychiatrist Dr. Abraham Flandings, whose career has floundered due to racial prejudice. He tracks the conspirators to their island retreat and approaches them with a new scheme…

As time passes, American industry has begun to fully embrace the possibilities of glass, paving the way for a future where glass has usurped metal and stone in many areas:

Their inventors made glass that was flexible, malleable and ductile, as strong as steel, pliable as copper, and useful as wood. Roads were made of glass bricks: it was used for roofs instead of slate or asbestos, and finally a complete house was put on the market, a house of glass, 100 per cent glass, six rooms complete, for $100.00.

The biggest development is in glass houses, which are so durable and affordable that “[s]uburban cities of glass sprang up like mushrooms over night” while “[i]n the South, the glass house was replacing the hut of the plantation hand and of the poor white.” All of this is presided over by a seemingly benevolent Glass Trust.

At the same time, however, America is hit by a nationwide decline in mental health:

In 1920 some states were caring for one insane person to every three hundred of its population. By 1930 the ratio all over the country was one in two hundred. […] When five more years had passed, the situation ceased to be a problem and became a menace, a threatening disaster, for the ratio was now one in fifty. Not a family but had at least one member insane.

No new mental institutions are built to help these people. “Instead large towns were confiscated, walled around with high wire fences and turned into concentration camps.” It reaches the point where two thirds of the American population is insane, and Congress is on the brink of passing a bill enforcing the execution of every insane person in the county.

But then one Professor Howens comes to the authorities. He reveals that he has been involved in a project to breed giant wasps: “by cross breeding with dragon flies and by feeding the later generations with thyroid and irradiating them with radium, we finally produced a species as large as a pigeon, with poison sacks like walnuts.” Why is this relevant to the mental health crisis? Well, he goes on to explain that the poison of these insects can place the victim in suspended animation (“We have frozen rabbits in cold storage, let them thaw, and when they recover consciousness, they seem none the worse for the freezing.”) Thus, he proposes, America’s insane citizens do not need to be euthanised; they can be merely drugged into a coma.

The professor also notes a correlation between the rise of insanity and the rise of glass houses, which leads to the mystery’s solution:

The scientists finally came to the conclusion that there was, in the sun’s rays, some healthful property that was absolutely necessary to the mental health of the human race. When men started to live most of their lives with glass between them and the sun, these rays were blocked, and absorbed by the glass in such amounts, that men became insane for the want of them. Pediatricians told of the healthful effect of sunlight in rickets, which effect was absolutely absent when the sunlight was filtered through window glass. The Senate called upon the Glass Trust to see if by their help a kind of mental health glass could not be made, but it was discovered that the Glass Trust had gone out of business.

This revelation – along with the production of the sleeping drug, which ends up being used on criminals as well as the insane – allows America to reshape itself for the better:

The million superior adults rose to the emergency and were equal to it. They showed mankind, once and for all, that a superior adult is worth ten ordinary adults, a hundred inferior adults, a thousand morons, a million imbeciles. No longer held down by the necessity of caring for the inferiors of the nation, the million real men and women worked wonders in a few years. Machinery, electricity, the atom were used as never before. Mankind no longer depended on its muscle but on its mind. In the United States a race of SUPERMEN was developing.

Back on the island hideout of the Powerful Ones, Dr. Flandings discusses how his plan backfired – for it was he who engineered the Glass Trust and the subsequent outbreak of insanity:

Back on the island hideout of the Powerful Ones, Dr. Flandings discusses how his plan backfired – for it was he who engineered the Glass Trust and the subsequent outbreak of insanity:

“We took a nation which contained every possible form of degeneracy, feeble-mindedness, criminality and potential insanity and we purified it. We were the direct cause of their being able to produce a race of superior adults. Not only that, but we were the indirect cause of their being able to keep it so. Now, every criminal, every psychiatric case, even every person who contracts syphilis is at once put to sleep.

They have a country free from crime, social diseases and nervousness. It did not take long for the mentally twisted of the world to learn to stay out of a country like that. The rest, of the world is degenerating as fast as it can, but in the United States every force is one of uplift, and righteousness.

“And we did it. We wanted to have our revenge and we did it.

“And because of what we did, it is a better, bigger country today than it ever was.”

As for the black population of America, well:

“Every negro was examined. If he proved to be feebleminded or diseased in any way, they put him to sleep. Those who were healthy were each given a thousand dollars and sent over to Liberia. At the present time there is not one negro in the States except those who are sleeping.”

But Count Sebastian has not given up. He arranges a scheme to infiltrate positions of authority in America, and replace the sleeping drug with “a powerful exciting drug… that will make a maniac out of a marble statue”, so that the country will be brought down by its newly-awakened population of lunatics and criminals. Ebony Kate pleads with him not to go through with it, that the plan will be thwarted once more; the men respond by setting off without her.

Three years later, Ebony Kate receives a visit from Taine, who has followed a trail to her island. Kate, resentful of being called “senile” by one of the other conspirators, spills all to Taine (“By the Seven Sacred Caterpillars!!” he exclaims) but before he can make a move the island is hit by a deadly storm. Stranded on the island with Kate, Taine begins plotting a murderous revenge:

“You are a Christian man, Mr. Taine. Please don’t go to your God with blood on yer hands.”

But Taine only laughed at her:

“Just like shooting so many rats, Kate. Those white niggers have been the ruin of my country and the pest of my life. I do not want them to think that they have raised all this Hell and will not be punished for it. I am going to hide when they come, and wait till they start their bragging, and then I am going to walk out and kill them—one, two, three, four, just like I hit those cocoa nuts, and then you and I will wait our chance and go back home.”

Eventually, Count Sebastian and his conspirators return to the island and inform Kate of their victory in America in awakening the sleepers (“Of course we cannot tell you every detail but it stands to reason that one million sane people couldn’t do much against over one hundred and fifteen maniacs”). As they drink a toast to their success, Taine emerges from hiding, He prepares to shoot the conspirators dead, but soon finds that Kate has already saved him the trouble by poisoning their wine.

Taine then heads back to America, where he finds that the problem was short-lived. It turns out that the drug used to revive the sleepers had the major side-effect of making them combust:

[D]uring all these years, the sleepers had been slowly using up their store of vitality, or energy, or whatever it was that kept them alive. Then, when the drug was changed, they became awake and started in to walk and talk and probably fight. This required a great amount of energy. In a short time they expended all they had. They simply dried up and died. There must have been something else, however, as there was not a trace of clothing or bone left and the scientists felt that there had been a spontaneous combustion of some kind. They could not explain it, but the dried bodies must have burned because around every little pile of white ash there was a trace of carbon, especially noticed on the streets.

The racial politics of “The Menace” are so ludicrous that it is easy to interpret the story as some form of satire. The very idea of black people and white people existing as equals is treated as a doomsday scenario to be averted at all costs; near the start, the banker Biddle is brought to a cold sweat by the prospect:

“Can you see what it means? If this keeps up for another ten years, New York will be a colored city! Those of us who are left here will either have to recognize the members of the race as social equals, or move out. Can you imagine the last white man in the city going through the vehicular tube in his automobile and never returning?”

In contrast to these histrionics, the author clearly shows a degree of sympathy for the antagonists, and gives them moments of dignity when they condemn the bigotry that they have suffered. Dr. Flandings, the villain of chapter four, describes the racial prejudice that he has faced in his career as a scientist: “Again and again I took civil service examinations and was placed at the head of eligible lists, only to be sidetracked when they found I was a negro”. Conspiracy leader Count Sebastian, gloating over his plan to turn white people black, laments how African-Americans have been viewed by white people as “their slaves and their playthings… little more than animals, and a little less than human beings… a higher type of ape.” Elsewhere, during the climax to the first story, a conspirator waxes lyrical about the evils of white privilege:

Throughout the white world, but especially among the Nordic peoples, the Caucasians could never forget that they were white and the negro was black, just as if the matter of color made any vital difference, That was the way they felt—we produced poets, playwrights, musicians, authors of no mean ability—and while we were made much of—they could never forget that we were black. Ten years ago a few of us gave up the effort, and looked for a way of escape—not from our race—but from our color. A peculiar and fortunate; combination of circumstances made some of us feel that the hand of God was in it and behind it, though no doubt our enemies more likely call it the claw of the Devil.

Taine responds by admitting that his opponent has a point: “It is not for me to say that you have not been wronged. No doubt you have, for thousands of years, but two wrongs never made a right”. However, he then blows these sentiments by saying, in the same paragraph, “You may turn the black man white but ultimately he will remain —just—a—nigger”.

Of course, the racially-charged supervillainy of “The Menace” is not especially unusual for its time. Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu stories, for example, have roughly the same level of racist content. But while Rohmer and his many imitators (such as W. J. Hammond, creator of Lakh-Dal) preferred Chinese villains, “The Menace” gives the world an African-American Fu Manchu in Count Sebastian – a dubious gift if ever there was one.

Looking past the racial politics (and, indeed, the eugenic undercurrent of part four) “The Menace” has some interest as a sort of proto-James Bond adventure, pitting its globetrotting hero against a band of dastardly megalomaniacs with an array of deadly inventions at their disposal. The inventions get sillier with each chapter, but they are at least novel. Certainly, few subsequent supervillains have considered building glass houses that drive people mad.

This was not the last that the world saw of Taine, as the dashing detective would have adventures in multiple magazines over subsequent years. The first sequel, “The Feminine Metamorphosis”, was published in Wonder Stories in 1929 and did for gender what “The Menace” did for race, with a cabal of evil women turning themselves into men.

Discussions

For the first time, Amazing Stories Quarterly includes a letters column, albeit a comparatively short one. Writing in response to Frederick Arthur Hodge’s A Modern Atlantis, Daniel J. Pflaum comments that “the entire principle of the seaport which the author describes, is entirely impractical”:

Now Mr Hodge has a number of steel bottles which are hollow and equipped with seacocks and air pumps. These displace more than their weight of water, and subsequently are buoyant. On these is balanced a heavy structure which forces them down until they are forty feet below the surface. Their buoyancy delicately balances the heavy superstructure. Even granting that this nice balance could be obtained by the use of the air pumps and sea cocks on the bottles, the slightest weight, even a small airplane, will disturb this equilibrium, and will sink the structure in a short time unless a very attentive engineer again establishes a balance.

The editorial response defends Hodge’s story: “The hydraulics and theory of floatation of the seaport is absolutely correct. The standards which rise from the submerged pontoons are what take care of the varying weights of airplanes”. Meanwhile, High school student Francis D. Uffleman (who notes that Edward S. Sears’ “The Atomic Riddle” helped him in his chemistry class) says…

When Mr. Pendleton (“The Nth. Man”) reached a weight of a few hundred tons, how was he able to obtain his supply of chemicals for sustaining the glandular stimulus causing his prodigious growth? A probable answer might be that these chemicals were cheap and common. Also, when he became a few miles in height, wouldn’t his voice become proportionately low in pitch so that it would sound not like ordinary speaking as heard through an amplifier, but like a series of terrific bursts of thunder, with no intelligible words? But enough of that It is sufficient to say that the story beats any I have read for a long time, and it is due for many more readings.

While Amazing Stories Quarterly served as a response to readers who wanted the magazine to come out more than once a month, Francis Vaillencourt is still unsatisfied: “I don’t think we get enough of the magazine. I think it should be a ‘Semi-Monthly’; it’s a long time between Quarterlies.”

Read My Profile