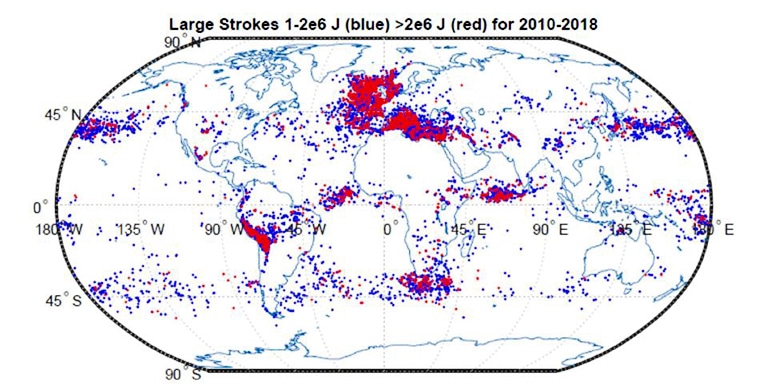

The new study maps the location and timing of “superbolts”—bolts that release electrical energy of more than 1 million Joules, or a thousand times more energy than the average lightning bolt, in the very low frequency range in which lightning is most active.

Results from the study show that superbolts tend to hit the Earth in a fundamentally different pattern from regular lightning, for reasons that are not yet fully understood.

You can see the map here.

Watching for superbolts around the world

“It’s very unexpected and unusual where and when the very big strokes occur,” says lead author Robert Holzworth, a professor of Earth and space sciences at the University of Washington who has tracked lightning for almost two decades.

Holzworth manages the World Wide Lightning Location Network, a research consortium that operates about 100 lightning detection stations around the world, from Antarctica to northern Finland. By seeing precisely when lightning reaches three or more different stations, the network can compare the readings to determine a lightning bolt’s size and location.

The network has operated since the early 2000s. For the new study, the researchers looked at 2 billion lightning strokes recorded between 2010 and 2018. Some 8,000 events—one in 250,000 strokes, or less than a thousandth of 1%—were confirmed superbolts.

“Until the last couple of years, we didn’t have enough data to do this kind of study,” Holzworth says. The authors compared their network’s data against lightning observations from the Maryland-based company Earth Networks and from the New Zealand MetService.

Lightning hotspots

The new paper shows that superbolts are most common in the Mediterranean Sea, the northeast Atlantic, and over the Andes, with lesser hotspots east of Japan, in the tropical oceans, and off the tip of South Africa. Unlike regular lightning, superbolts tend to strike over water.

“90% of lightning strikes occur over land,” Holzworth says. “But superbolts happen mostly over the water going right up to the coast. In fact, in the northeast Atlantic Ocean you can see Spain and England’s coasts nicely outlined in the maps of superbolt distribution.”

“The average stroke energy over water is greater than the average stroke energy over land—we knew that,” Holzworth says. “But that’s for the typical energy levels. We were not expecting this dramatic difference.”

The time of year for superbolts also doesn’t follow the rules for typical lightning. Regular lightning hits in the summertime—the three major so-called “lightning chimneys” for regular bolts coincide with summer thunderstorms over the Americas, sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia. But superbolts, which are more common in the Northern Hemisphere, strike both hemispheres between the months of November and February.

The reason for the pattern is still mysterious. Some years have many more superbolts than others: late 2013 was an all-time high, and late 2014 was the next highest, with other years having far fewer events.

“We think it could be related to sunspots or cosmic rays, but we’re leaving that as stimulation for future research,” Holzworth says. “For now, we are showing that this previously unknown pattern exists.”

The study appears in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres.

Additional coauthors are from the University of Washington and the University of Otago in New Zealand. Funding for the research came from the University of Washington.

Source: University of Washington

This article was originally posted on Futurity