UPDATE: Given the attention that this article has received from certain quarters, I now feel it is necessary to mention one scenario under which it is possible for a relatively small group of active social networkers to “fix” the final outcome of the Hugo Awards. You’ll need to read the entire article to fully understand the context of the scenario, which goes like this: if the suggested nominees from a voting block manage to garner enough nominations to occupy the top five slots in any given category, then the final ballot (for that category) will only reflect the voting bloc’s nominees. Under that scenario, the only way to insure that the bloc’s slate goes unrewarded is for the majority to place NO AWARD above every single other nominee on the final ballot. This is unlikely, as the vast majority of voters exercise their vote independently, preferring it to represent their personal choice rather than that of a political agenda.

FURTHER UPDATE: Note to people arriving from other sites who plan to comment: Many of your confederates display a distinct lack of comprehension. If you wish to avoid the same, realize that this piece lays out possibilities – NOT recommendations.

FINAL UPDATE: Neither I nor Amazing Stories supports bloc voting or Hugo Award Recommendation Slates in furtherance of political agendas. There is a strong distinction between an “Eligibility” post and organizing a group vote. Failure to recognize the difference is usually deliberate.

Note: this article was prepared with the assistance of a former Hugo Awards administrator. Some of the information provided is based on notes received from that individual who was provided with a draft of this article for review.

Back in the days of paper and dial telephones (? – look them up), it was A: nearly impossible to fix the Hugo Awards and B: nearly impossible to determine whether or not the voting had been fixed.

It was nearly impossible to put the fix in because there was no meaningful information to be had about the likely number of voters; no real ability to line up a voting block, no easy, time-sensitive way to coordinates one’s efforts.

On the other hand, the gathering together of ballots, the counting and calculating of the votes, the publishing of the short list and the dissemination of the ballots was handled behind closed doors by a very small handful of individuals; if they decided to collude, there’d be no track record to investigate, no forensic bread crumbs that could be followed back to the guilty party(s).

What little information was to be had about the process was disseminated by the very people doing the tallying who essentially only had ethical guidelines to guide them.

Pause for clarification: with one possible exception, I am not accusing or even suggesting that in the grand old days of paper, any Worldcon committee or any Hugo Awards potentate fixed the vote. I do believe that in all but perhaps that one case, the parties responsible handled their duties the way the Suncon folks did (the convention I worked on during which I was closest to the process; I handled a lot of the mail; I was not allowed to open ballot envelopes; merely tally the name against registrations and hand them off to a lock box for transfer to the awards committee members.)

That exception takes place during approximately the same era. (I’m going public with this for the first time btw, so, scoop to me.) I had a close and dear friend up for a major award. Nominations for that year’s Hugos went just fine, but when it came time to fill out final ballots, a huge (relatively speaking) number of eligible fans in the east/north east region of the country never received their ballots in time to vote for the finalists. I was one of those who never got a ballot. I know several others who did not either. I know there was a lot of buzz at the convention itself, most of it hush-hushed; I know there was little if any follow-up afterwards.

My friend, a fan and author, was very popular in the specific region of the country that did not receive ballots; since the ballots were mailed out via bulk mail, it would be relatively easy for someone to “fat finger” the zip codes, or simply short the piles intended for those zip codes. If someone knew the total number of likely voters (information easily guesstimated from the number of nominating ballots returned, the then current number of registered convention members and trends from previous years), it would be a relatively simple matter to short the potential votes for my friend.

Given that the person who did win the award that year has been whispered about regarding possible politicking for other awards and has engaged in other subsequent activities that suggests politics is not an unfamiliar playground, the belief that there is a good chance that this author and a few fans “did something” to manipulate the vote has stayed with me these past 35+ years.

If some people would be willing to open up (and I’m pretty sure they could identify themselves if they read this) the question of whether they did or did not fix the Hugos could be answered in pretty short order. The fact that so many of the people who were directly involved haven’t talked about it in 35+ years – or are unwilling to voice their beliefs and opinions in anything other than very vague terms, is certainly suspicious – but we should always keep in mind that there are probably good reasons not to say anything even if nothing happened. So we’ll probably never know (unless this piece manages to evoke mea culpas, which I very much doubt it will).

But that was, as they say, 35 years ago. A life time for many. The deep, dark, unimportant past for most. Except for one thing. It is a case of possible vote fixing from an era in which the fixing was much more difficult than it is, potentially, now.

Turning to the now, the first question I’d ask is: how vulnerable to hacking is the online voting system?

Worldcon websites are hosted on servers connected to the web. Because they are connected to the web, there are a number of possible security vulnerabilities and several different fixes that could be worked depending upon the level of hacked access achieved. Incoming ballots could be altered before they are aggregated and/or the tallying itself could be altered. (If I were doing the hacking, I’d prefer the former; copy the incoming ballot; use that info for confirmation with the voter, alter the data that goes to WSFS for tallyiing. That would make nearly every voter a party to the fix and would make it virtually undetectable.) And consider that a failed and exposed hack might be even worse in the long run….

I will pause to recommend the following: that WSFS put together a committee or task force whose sole function will be to devise a recovery plan that will be utilized if something disastrous happens during the course of voting for the awards. That “something disastrous” could range from natural disaster to alien invasion and everything in between. I’d like to know that if I voted, and something completely destroyed (or rendered unusable) all of the records prior to the votes being finalized, there was a methodology in place that everyone has access to. (Back in High School I uncovered a ballot stuffing scheme during school elections for Senior Class officers. Nothing like that had ever happened and the administration decided the best solution was to have both tickets serve simultaneously, thus basically robbing every student of their franchise. I filibustered the special emergency student council meeting, led a walk out and called in the mainstream press until it was decided to hold the voting over again. Worldcon and Fandom at large does not need to go through something like that.) Additionally, Worldcon/the Hugo Awards are time sensitive. A “fix” needs to be formulated well before there is ever a hint of a need for such a thing. That could be something as simple as “we won’t give out awards that year” to planned backups and storage of the information in 16 different widely separated geographic locations, complete with an armed guard. I really don’t care what the methodology is, as long as there is one. Yes, it’s unlikely to be needed, but balancing that out is the fact that once done it never be done again.

Now, back to our regularly scheduled program.

The next question I’d ask is – how much is a Hugo Award really worth?

(Anyone with anything approaching solid sales numbers for a work before and after winning the award could provide some instructive information here.)

Money of course is not everything (though some authors we’ve discussed recently would have you believe otherwise). There is prestige, ego, vendetta, politics, messianic vision, revenge and relatively mild forms of insanity that can motivate here as well. Or (an increasingly likely scenario these days) the hacker mentality: person or persons doing it just because they can. (Which makes me wonder: has anyone ever extorted anything through NOT exploiting uncovered vulnerabilities?)

See, when you add Machiavellian thinking to science fiction fandom, there are very few scenarios that can be eliminated out right.

Finally, I’d ask – how much longer will it be before the promulgation of suggested vote slates turns into vote buying? – if it hasn’t already.

When it comes to buying a Hugo, there are two hurdles to over come – the initial nominating hurdle and the final vote hurdle.

Key to influencing both is a good solid estimate of the total number of likely voters.

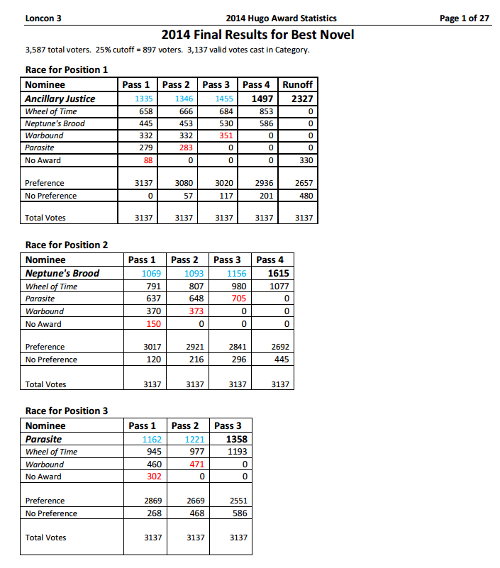

WSFS, and fandom in general, usually operates on the principal of open access. You can go to two online sources to get the baseline numbers you’d need to figure this all out. The first is TheHugoAwards.org, specifically the Hugo History tab. There you’ll find all of the available information on the winners, the nominees and a goodly percentage of the also rans, along with nicely tabulated data on the total number of ballots, total number of votes and which works received what votes. For example, if you take a look at the PDF (scroll ALL the way down) for this past year’s awards (Loncon3), you’ll see something like this:

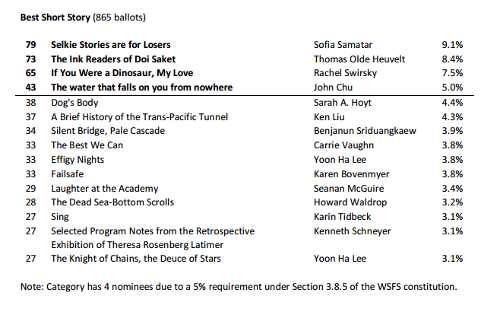

and (note the page 1 of 27) further on down, something like this:

Note three things about that second image: first, the dividing line between 4th and 5th place. 5 nominating ballots stood between Dog’s Body and appearance on the final ballot. Five. One hand’s worth of placement on a ballot (where it could have been listed in any one of five different places – you get five nominations per award category during the nomination process.)

The second thing and the third thing are tied together. The note at the bottom references the 5% rule. That is, an eligible nomination for the final ballot must be in the top five numerically by total vote count, but it must also have received at least 5% of the total number of ballots cast, which number (the third thing) is conveniently provided for us at the top. 865 ballots were cast for short story. 5% of 865 is 43.25, rounded down to 43. Thus, the disqualification of Dog’s Body.

(Also note that since each individual voter can nominate up to five works for this category, those 865 ballots represent 865 individuals casting anywhere from 1 to 5 votes in each awards category. The range for this particular category is, therefore, as few as 865 nominations (1 selection by each voter) to as many as 4,325 (five works nominated by each individual voter). In this particular case, 578 individual works were nominated.

Not even ten percent of the members cast a ballot for Short Story. Sad. This lack of participation is one of the award’s major vulnerabilities, as we shall see. (In point of fact, many nominating ballots were received while Loncon3 was in the early stages of obtaining memberships and therefore the percentage of members nominating for short story is a larger percentage of the membership than is suggested by the eventual total membership. Estimates put participation in the nominating process at approximately 15% of then current membership numbers.)

Details on how the voting works and how votes are calculated is also available on the same website.

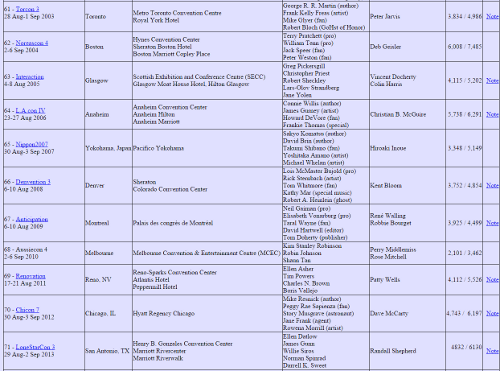

To gain historical insight into how many people are likely to vote, we can turn to the Long List of Worldcons, where you’ll find this:

Here’s a more readable version with the middle stuff removed:

You’ve got the name and date of the convention, followed by two numbers: attending members/total members. The difference lies in the existence of “supporting members”. One can join and support the Worldcon for a lower fee than an attending membership. One can also obtain nominating privileges by being a supporter of the following year’s Worldcon. (Members of Loncon3 can nominate for this year’s awards. Members of the 2016 Worldcon can also nominate, as can obviously both attending and supporting members of this year’s Worldcon. However, only members of this year’s Worldcon – Sasquan – can participate in the final round of voting.The key is, supporting members (provided they support far enough in advance) are eligible to nominate for the Hugo Awards. The total number of eligible voters is, therefore, some large percentage of the total membership number (not just the attending members number), while the total number of eligible voters during the nomination process is an aggregation of the membership from the preceding year, the membership of the current year and anyone who has acquired a membership for the following year – approximately triple any given year’s attendance numbers. (Our Awards administrator also points out that a not small percentage of members are members of the preceding, the current and the following year’s conventions, but they do not get three votes, only one like everyone else.)

(Complicating what looks pretty straight forward here is the fact that both attending and supporting members of the previous year’s convention AND attending and supporting members of the following year’s convention are also eligible to nominate – numbers that are not reflected in the preceding tables.)

Our former awards administrator also hastens to point out that the only people likely to have a solid grasp on the number of voters participating in the final vote are the administrator(s) themselves. Which, to offer a straight-forward assessment is both a benefit (it mitigates against gaming the system) and a potential vulnerability.

This data, combined with the vote data from The Hugo Awards website can be used to guesstimate future voting trends. Though Loncon3 will throw statisticians for a loop because, unlike previous “foreign” Worldcons, it actually had increased attendance over previous years. (Worldcons held outside of the US/Canada have historically had lower membership.)

The BIG question for odds makers is: will Sasquan continue the upward trend or should we pull Loncon3’s numbers from the data? In other words, will Sasquan have total attendance somewhere around 11-12k, or somewhere closer to 7-8k?

Probably best to work both scenarios.

What we do is take the attendance numbers from the Long List and weave the Hugo voting numbers from The Hugo Awards data together. We’ll only look at two award categories to keep things manageable.

LoneStarCon3 had total membership of 6,130 a 2% reduction from the previous year.

1,113 ballots were cast for Best Novel – 18% of the total (known) voting pool, with a minimum of 55 ballots needed to qualify. 118 votes were cast for fifth place.

662 ballots were cast for Short Story – 10.7% of the total voting pool, with 33 votes needed to get on the final ballot. 34 votes were cast for third place (the 5% rule eliminating the last two slots).

Chicon7 had total membership of 6,197, a 12% increase from Renovation.

958 ballots were cast for Best Novel – 15% of the total voting pool. 47 votes is the cut off. 71 votes were cast for fifth place.

611 ballots case for Short Story – .10% of the pool. 30 votes is the cut off. 36 votes were cast for fifth place.

Renovation had membership of 5,526, a 12% increase from the previous North American convention (Anticipation. Aussiecon 4 intervened)

833 ballots for Best Novel -15% of the pool. 41 votes was the cut off. 78 votes were cast for fifth place.

515 ballots for Short Story – 9% of the pool. 25 votes was the cut off. 29 votes were cast for fifth place.

And so on through however many Worldcons there is data for.

I’d hire a statistician if I were going to do this seriously. As it is, we’ll just suss out trends using various unscientific methodologies and I see a few things here worth mentioning: First, if one assumes a continued upward trend in Worldcon attendance growth, it would be reasonable to assume something on the order of 12 to 15%. If we drop Loncon3 from the equation, we’d expect Sasquan to see something like 7,050 members.

Likewise, we’ll probably continue to see voting participation numbers for Best Novel somewhere around 15 to 20% of the total membership. In this case – 1,057 to 1410 ballots cast. Short Story will continue to be low, somewhere around 10% or 700 some odd ballots.

The cut off (which sort of translates into the least number of votes needed to reach the final ballot) for novel would be 52 – 70 votes, while the same for short story would be 35.

But note one thing: while the cut off for short story is usually pretty close to the 5% requirement, that for novel is usually around a bit more than double the cut off.

What’s that all mean? Well, if you paid me a bunch of cash for my advice on how to fix the Hugo Awards in your favor next year, I’d tell you that if you wanted to get your novel onto the final ballot, you’d need to buy (or suborn) 150 Supporting Memberships (preferably suborn since you don’t want to inflate the actual voting pool as that will increase the number of votes you’ll need to buy); and if you wanted to make the final ballot with a short story, you’ll need to ‘buy’ around 40 votes.

Sasquan’s Supporting Membership fee is, right now, $40.00. Your final ballot nomination for Best Novel will cost you $6,000. Your final ballot nomination for Best Short Story will cost you $1600. Bonus – everyone gets to vote in every category, so for your $6,000, you’ll get that nod for Short Story as well – but most likely won’t get to fix the award for Best Dramatic Presentation, Long Form (that category gets a lot of votes.)

Six Thousand Dollars is the current going price of a Hugo Award Final Ballot nomination. (As an exercise in potential humility, we’ll actually get to see how close I am with these numbers later on this year.) Bumping that number up to $10,000 – which gets you 250 votes – would be a sure thing.

It may actually cost you a bit more since it might take some favors or some additional cash to actually obtain the proxies for all of those votes. I’m pretty sure there are at least a few authors out there with a large enough following of loyal and rabid fans who’d say “hell yeah!” if their favorite author sent them a check for $40 bucks and asked them to buy a supporting membership and then forward the electronic voting ID info to them.

Is getting to stick HUGO NOMINEE FOR BEST NOVEL up on your website worth $6,000? If I had that kind of disposable income, it would be for me. (I’ll pledge right now that I will NEVER engage in this kind of activity, either for myself or for anyone else’s benefit, for any Hugo Award category. Furthermore, if I ever find out that someone else is doing it, I’ll rat them out in a heart beat.)

Is getting to stick HUGO NOMINEE FOR BEST NOVEL up on your website worth $6,000? If I had that kind of disposable income, it would be for me. (I’ll pledge right now that I will NEVER engage in this kind of activity, either for myself or for anyone else’s benefit, for any Hugo Award category. Furthermore, if I ever find out that someone else is doing it, I’ll rat them out in a heart beat.)

Now the next question is, will that same $6000 investment get you the win?

The problem of course is that voting starts all over again with the final ballot, and they use that funky system of redistributing the votes following each round of tallying. (First choice votes are tallied. The last place is dropped. The ballots are tallied again, with the second choice on each ballot being added to those from the previous round. Last place is dropped again, and so on. To be a little less murky: suppose you voted for novel B as your number one choice and novel A as your second choice. The votes are tallied and novel A is in the number one position. Novel E comes in fifth and its dropped. On the second round of tallies, novel B would continue to see your vote, since it was your second choice. Once novel B is eliminated, your next selection would get your vote. Let’s suppose that novel B gets eliminated in the second round. Your second choice, for novel A, then gets counted and added to the tally for novel A. Not clear? Find a Hugo Awards Administrator to ‘splain it to you.)

Of course, your investment in proxies still holds, you’ve got 70 ballots to cast. But that represents only the minimum needed to make the final ballot. Time to go back to those PDFs on TheHugoAwards.

Lets use 2013 as an example. John Scalzi’s Redshirts took home the bacon for Novel that year. A total of 1649 ballots were counted (meaning ballots with one vote thru ballots with 5 votes).

Redshirts was in first place right from the start, receiving 407 1st place votes. It picked up 1 more vote in the second round (meaning 1 voter had placed Redshirts as their 2nd choice and No Award as their first choice. Since No Award was dropped after the first round of tallying, that ballot’s second pick – Redshirts, picked up one vote.). It picked up another 91 votes in the third round (91 votes on ballots that had placed two other picks in 1st and second), 134 more in 4th and a final 194 in fifth, for a final total of 827 votes.

How do you beat that system? Well, for starters, if you look at the historical record, winning works end up receiving pretty close to 50% of the final vote tally. (Which is kinda a ‘duh’ revelation.) Guess how many folks are going to vote in the final round (in this case 1,649). Take 50% of that – 825 – and you have your answer. If you’d done this at LoneStarCon3 and bought yourself 825 proxies, you’d have won Best Novel for the cost of $33,000. (How many of you earned that much from a single novel?)

But.

It ain’t that simple. Our Former Administrator informs us that the process is not a simple one of merely collecting all of the completed ballots and tallying them. The issues covered here are ones that Hugo Awards Administrators have been wrestling with for YEARS. To quote from the notes:

It ain’t that simple. Our Former Administrator informs us that the process is not a simple one of merely collecting all of the completed ballots and tallying them. The issues covered here are ones that Hugo Awards Administrators have been wrestling with for YEARS. To quote from the notes:

Administrators have fairly sophisticated tools to detect things we consider to be fraud… and unlimited power to tear those ballots up without question or need to report that it was done. Those ballots (both nominating and voting) are never reported in any of the totals as they’re not valid and were not part of the process.

Which of course means that even the information on the Hugo Awards website does not necessarily show us the whole picture. How many ballots were tossed as invalid? Could be 0, could be total membership minus 3,587 (for best novel). In other words, it’s possible that the number of ballots deemed invalid far exceeds the number of valid ballots. Which, considering that the “methods” used to evaluate fraud and invalidity are not shared, strongly suggests that buying votes or proxies has as much chance of effectively fixing the vote as that poor stowaway in Godwin’s The Cold Equations has of reaching her destination alive.

EG: None.

The conclusion reached (and supported by our Former Administrator) is this: It IS possible to engineer an appearance on the Final Ballot, to gain the position of Hugo Nominee. It is NEXT TO IMPOSSIBLE to engineer a win. Our former administrator states –

it’s possible to social engineer yourself onto the ballot without spending money. What was done by the “sad puppies” slate was not considered to be fraud, but you may note that they didn’t fare well in the actual voting (even coming in behind “no award”, which is exceptional). The voting population generally frowns on social engineering nominations….it was done a good while ago by the scientologists with the same result (coming in dead last) I would hope it’s a similarly long time before we see such engineering again as it diminishes from the awards. Such things are possible in *any* open-to-anyone voting system, we do our best to avoid it and it doesn’t help anyone to advocate it.

I don’t think it really makes much difference whether you call it “social engineering” or “vote buying” – it amounts to having the same effect, and as stated above, the community of voters takes a dim view of such practices. Two times that we know of people have tried and two times they’ve been rewarded with the ignominy of coming in at the bottom or coming in below No Award. (The voters would rather have NOTHING than recognize your work!) That’s the result of the vote itself. In terms of social cost – who knows? It could be that participating in such schemes will cost you votes well into the future.

Solutions? The number 1 solution is to encourage more people to attend Worldcon and to encourage more members to participate in the vote. I’m buying my membership today and I will be nominating and voting. The larger the valid voting pool is, the harder (and more expensive it can become) for anyone to engineer their way onto the final ballot.

Solutions? The number 1 solution is to encourage more people to attend Worldcon and to encourage more members to participate in the vote. I’m buying my membership today and I will be nominating and voting. The larger the valid voting pool is, the harder (and more expensive it can become) for anyone to engineer their way onto the final ballot.

It may also be that delaying the distribution of the information regarding the number of registered Worldcon members until after the nominating ballots are finalized would help – it certainly would make it more difficult to guesstimate how many minions you’d need to sway.

Running close second to the number 1 solution is the community continuing to voice its objections to voting slates and maintaining enough self-respect to avoid participating in the same.

(In the interest of full disclosure: The Hugo Awards are named for the founding publisher and editor of Amazing Stories – Hugo Gernsback.)

For the value of a Hugo see this post by Kameron Hurley: https://www.kameronhurley.com/what-i-get-paid-for-my-novels-or-why-im-not-quitting-my-day-job/

To her it’s already been worth $13,000 per novel.

As for reducing the possibility of this sort of attempt to buy a Hugo – the simplest thing is to encourage the existing members to nominate, and to do so in every category.

Your solution echoes the one I’ve put forth and others have as well: greater participation across the board is the right, best and most effective “fix”. However, many active voters have expressed discomfort in nominating in categories where they have little or nor familiarity with eligible works. I’d therefore suggest that the most effective place to put effort is to encourage greater participation of any kind.

What I’d actually like to see is the creation of a Hugo Awards Voter’s Group, in which each member has pledged to both nominate and vote for works that they feel are deserving of the honor, and to never nominate or vote for any reason or motivation that is external to the award.