(Ed. Note: You can read Part 1 of John Dodd’s My Science Fiction Childhood here)

I would always experience a surge of excitement in finding a Pan collection of science fiction stories, or a new Doc Savage, or an Algys Budrys, or equally great, a science fiction author unknown to me but presented through a highly arresting space age illustration with spaceships and aliens and even once in a while a glamorous female astronaut in an extremely close fitting spacesuit who, for some reason, always seemed to be in the claws of some intergalactic crustacean or a mad scientist with thick glasses and mad hair and a leer.

Of course the pinup style of covers were mainly American pulps. British publishers, it seemed, were either too classy, or too repressed, for that sort of malarkey. Instead, publishers like Pan and Penguin offered stylised visions of the cosmos, or arresting views of alien planets with fields of stars and comets as their backdrops. If there were a spacecraft present they would be a tasteful, low key ones added, almost as an afterthought, as a small, discreet element in the otherworldly landscape rather than the militaristic shiny phallic symbols offered by “the Americans”.

Of course in my view us Brits either wouldn’t or couldn’t write science fiction. Initially I believed Arthur C. Clark to be American, for instance, and while John Christopher and John Wyndham were doubtless extremely good authors, they weren’t really science fiction writers, were they? Christopher’s novel about mutating vegetation and Wyndham’s one about a village of peculiar children somehow never really grabbed me the way a Galaxy-spanning Heinlein or Frank Herbert did. I radically revised my opinion about British writers (including Christopher and Wyndham) later on, however – when my tastes had matured somewhat.

By the time I had reached my early teens, music became the secondary (or perhaps first equal with reading) most important force in my life. The music I listened to, and how it informed my later tastes, have strong parallels with my developing reading life. Strangely enough.

When I was young the radio played mainly easy listening orchestral, dancehall, and Scottish folk music. I use the term “folk music” advisedly; it wasn’t true folk music, since it mainly involved accordions – not a traditional Celtic instrument, as far as I am aware. The staple diet, though, seemed to be the favoured by our parents, such as Matt Monroe, Shirley Bassey, Tom Jones , Frank Sinatra and Frankie Vaughan. Vaughan and Monroe were, of course, low rent versions of Sinatra, another parallel with science fiction in which the Brits lost out yet again.

When my parents first heard The Rolling Stones, I remember them being thoroughly disgusted – though dad, like myself, grew to love rock music, but only if you consider the output of Status Quo as bona fide rock music. Which I don’t.

While the BBC gradually introduced soul music, and some rock and pop, to get a steady diet of the only kind of music that mattered, one had to tune in to Radio Caroline or the late night Radio Luxembourg. Luxembourg was somewhere foreign, that was all I knew, and they played some pretty good stuff, not only Motown and The Beatles but also bits and pieces of what I later learned was called progressive rock. In much the same way that the novels of Robert Heinlein knocked my socks off, hearing Jethro Tull for the first time and, more significantly, Pink Floyd, was nothing short of a revelation. On the road to Damascus I had finally seen – or rather heard – The Light.

Lying on my bedroom floor with headphones plugged into my turntable, I would listen in the dark, to Pink Floyd setting the controls for the heart of the sun, or several species of small furry animals gathered together in a cave and grooving with a pict. In the Floyd I had found a pure distillation of science fiction. It was a soundscape that took me out of my body, and into another place more quickly, and somewhat more intensely than even the very best science fiction could.

But these aural landscapes felt more transitory than a good book. They were sweets rather than a meal. They were sex rather than love (although at best they could be both, but never as prolonged an experience as a good book).

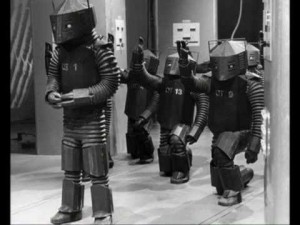

Almost in tandem with the arrival of Pink Floyd, came Doctor Who. I can remember the grumpy William Hartnell, with the long grey hair, the very first doctor, going back in time to the stone age with his extremely well-spoken Oxbridge assistants. The original Doctor Who cast would no doubt be horrified by the cockney mini-skirted Rose, and the pansexual Captain Jack Harkness of later years. I honestly don’t think I was impressed with those early episodes with the black and white cavemen and unconvincing sets and even less convincing dialogue. Nor did the appearance of shambling antlike aliens do much for me, though I confess to enjoying them much more than pre-Magnon man. But, in common with others of my generation, it was the first appearance of the Daleks, that finally sold me on the series and made it compulsive viewing from then on. I did not, however, as did my wife when she was a young girl, hide behind the couch when the Daleks came onscreen screeching the word “exterminate” over and over. If anything, I couldn’t get close enough to the set. For some reason, both my brother and I loved these monsters that resembled inverted ice cream cones with a bad case of acne. Their sucker or gripper arm, unlike their protruding laser-type weapon, seemed to serve no purpose other than to wave stiff-limbed at their enemies. What was it about those Daleks, I wonder? Unless they were on a flat surface, for example, they couldn’t move. Negotiating steps or even slightly uneven ground, for instance, was a complete no-no. As for that little weapon that resembled a sort of elongated egg whisk, it didn’t have much manoeuvrability and I imagine it would have been fairly easy to get out of the way of its death ray if push came to shove.

However, it was once again the US invaders who impressed me the most. After much begging and pleading my parents would let me stay up late to watch The Outer Limits. Two episodes stick in my mind. One involved escaped alien criminals called The Zanti Misfits, vile little insect creatures who made my skin crawl. And another was the case of a man who, using some kind of injection, could plasticise his face so he could mould it to look like anyone he wished; punishment for his evil activities involves having his face pulled out of shape, so his eyes and mouth became welded shut. Both these episodes gave me horrid nightmares for weeks. Yet I absolutely refused to stop watching the series. It was, after all, good science fiction. If sleeplessness and nightmares were the price to pay, then so be it.

There were a slew of other unmissable series on our small black and white telly, too. The Twilight Zone, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Lost in Space (my favourite) and much more. The BBC around this time also did a great series called Out of the Unknown, based on science fiction stories by famous authors. Episodes included adaptations of Isaac Asimov’s The Dead Past and Sucker Bait, Ray Bradbury’s The Fox and the Forest, Kate Wilhelm’s Andover and the Android, J.G. Ballard’s Thirteen to Centaurus, and Robert Sheckley’s Immortality Inc. among others.

Science fiction was as abundant on television back then as it is today. Even without computer generated graphics all these series were nevertheless arresting at, at the time, revolutionary.

There were science fiction films to see, too, of course. Many of them B films such as the memorably awful Night of the Lepus, involving giant carnivorous rabbits – I kid thee not. But it was on television, rather than in the cinema, that I was introduced to such classics as The Incredible Shrinking Man, and The Thing. One of my favourite films in the cinema from that period also involved shrinking, Fantastic Voyage, based on an Asimov story and involved a submarine taking a medical team into a dying man’s brain to destroy a tumour. The scenes involving white corpuscles enveloping and killing some of the tiny humans were, I think, revolutionary and weirdly more plausible than any alien invasion. I also vividly recall my father sneaking me in with him to the cinema to see Barbarella (I was underage) and, naturally, I became besotted with Jane Fonda on the spot. Of course Forbidden Planet, featuring Robby the Robot who would later appear on Lost in Space became my absolute favourite film of the time. It did not surprise me to learn, much later in life, that the story was so good because it was based on Shakespeare’s The Tempest. So, arguably the Bard was a genre writer, too – who knew?

Without going into detail about any more books, films, music or other manifestations of my science fiction childhood, I know I can say one thing about my addictive reading habit, and this is the note on which I shall end this short essay.

Science fiction saved my childhood. And for that, and for much else since, I can only thank it.