Are some histories better left buried? One of the individuals you’ll likely never see in a science textbook is the researcher (and resurrector) Dr. Robert Cornish (1903-1963). His story of somewhat successful reanimation begins in the 1930s with a series of dogs all dubbed Lazarus and ends with a California prison.

In the Beginning

Cornish was a child prodigy, graduating from the University of California, Berkeley at the age of 18. By the time he was 22, Cornish had his doctorate and had already begun experimenting with a series of different projects. None sparked his interest so much, however, as his forays into the idea of bringing the death back to life. In 1932, the scientist developed a curiosity about whether or not he could start a heart beating after it had already stopped. Cornish wasn’t the first to consider these experiments–in the 1900s, Dr. George Washington Crile had already set the example. Through adrenaline, chest massage and saline solutions, Crile had managed to revive dogs after death. His method failed. While the heartbeat resumed, Crile’s test subjects died a second time moments later after blood clotting set in.

Fox terriers were the subjects chosen by Cornish for his experimentation. He dubbed each dog “Lazarus” after the Biblical figure resurrected by Christ days after his death. (Later on, the dogs would be dubbed by the press “Lazarus I,” “II,” “III,” etc. Cornish seems to have made no such distinction.) His initial funding was supplied by grants, his laboratory based out of a barn-like campus structure on the University of California.

Method of Resurrection

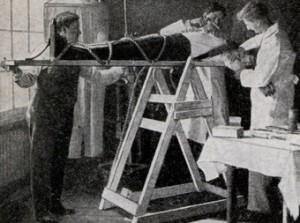

Each one of the dogs in Cornish’s experiments was killed using a nitrogen gas mixture and left clinically dead for six to ten minutes before any attempts to revive them were made. Each dog was placed on a “teeterboard,” a seesaw-like contraption upon which it was strapped. Cornish opened one of the thigh veins, injecting a saline solution saturated with oxygen that contained adrenaline, a liver extract (heparin) and canine blood. As he performed CPR on the animal, an assistant rocked the teeterboard back and forth to stimulate heart motion.

The first three canines resurrected this way came to life only briefly, slumping into comas thereafter. The first dog lived 8 hours, the second 5. For the third Lazarus experiment in 1934, Cornish switched his solution, adding gum-arabic to keep the heart from overworking. Still not convinced of failure, Cornish tried again.

Cornish Continues

Lazarus IV managed to show remarkable improvements over III, with nearly normal pulse, elevated blood pressure, and the ability to eat liquid food. It learned to bark, crawl, sit up and managed to consume meat after thirteen days had passed. It was blind and unable to stand.

Lazarus III was the closest to success thus far for Cornish but it wasn’t close enough. Semiconscious for over 2 weeks, Lazarus brought media attention to Cornish and his experiments. This attention made the University squeamish and Cornish was asked to leave. The Berkeley Daily Gazette reported “he [Cornish] admits that the dog, more dead than alive, is decidedly not an ideal house dog but it appeared most likely that he would have to take the animal to the home of his parents.”

It is not reported what the elder Cornishes thought of this idea.

The backlash against Cornish wasn’t contained to the university–several members of the public complained as well. The scientist debated about switching test subjects from canine to swine, explaining “hogs more nearly resemble humans in their digestive and circulatory systems and have far fewer friends than dogs.” But he continued conducting experiments with fox terriers, now in his home rather than the laboratory. The fifth Lazarus recovered more rapidly in four days than the fourth had in thirteen. In neither case, however, did the dog resume a normal life.

From Hounds to Humans

Robert Cornish became convinced that he could achieve success with human experimentation. Believing that he would achieve the greatest results from asphyxiation-related deaths, Cornish petitioned Arizona, Nevada, and Colorado governors to furnish him with the bodies of criminals perishing in the gas chambers. The petitions were rejected but hearing of his strange requests, a number of would-be subjects offered themselves up for experimentation. One Kansan suggested that $300,000 would be a fair price for Cornish to offer him for the use of his body. (Cornish took none of those offers up.)

The scientist pressed on, using an artificial heart in his work, until he was contacted by San Quentin death row inmate Thomas McMonigh. California had recently adopted use of the gas chamber and this fact caused Cornish to leap at the offer. He told The Mail, “he [McMonigh] wants me to bring him back to life after his execution in the interest of science.”

The state of California had different ideas. Cornish’s request was considered but there was determined to be one flaw with the plan. The petition was denied, not because of the immorality of experimenting on prisoners but because legal opinion differed on what McMonigh’s legal status would be after resurrection. Would a prisoner killed and then brought back to life still be subject to the death penalty? What kind of precedent would it set? This marked the last of Cornish’s experiments to reach the public’s attention.

A Legacy in Film?

During the Lazarus experiments, Cornish excited much interest in Hollywood. Boris Karloff starred in two films inspired by Cornish’s work, The Man they Could Not Hang (1939) and The Man with Nine Lives (1940). The scientist actually served as consultant to the former film. These movies sparked a “mad scientist” craze in science fiction, and were also among the first to conceptualize open-heart surgery. Karloff recalls in the Scott Allen Nollen biography, “The scriptwriters had the insane scientist transplant brains, hearts, lungs and other vital organs. The cycle ended when they ran out of parts of anatomy that could be photographed decently.”

During the Lazarus experiments, Cornish excited much interest in Hollywood. Boris Karloff starred in two films inspired by Cornish’s work, The Man they Could Not Hang (1939) and The Man with Nine Lives (1940). The scientist actually served as consultant to the former film. These movies sparked a “mad scientist” craze in science fiction, and were also among the first to conceptualize open-heart surgery. Karloff recalls in the Scott Allen Nollen biography, “The scriptwriters had the insane scientist transplant brains, hearts, lungs and other vital organs. The cycle ended when they ran out of parts of anatomy that could be photographed decently.”

This wasn’t the weirdest of Cornish’s Hollywood connections. The film, Life Returns (1935), was heavily inspired by the work that the scientist had done. In fact, actual footage from Cornish’s experiments was inserted into the end of the film. The resurrection of Lazarus was spliced with clips of actors playing the roles of doctors and nurses searching for an end to death.

For the most part, these movies are what remained of the work of the little-known Cornish. While his predecessor Crile went on to other avenues of scientific research, Robert Cornish ended his days by developing and selling his own brand of toothpaste. His resurrection studies are now buried in the dusty pages of old magazines.

To Dig Deeper

Though Cornish’s work is not easily found, traces of it can be glimpsed by searching the Google News Archive. Of particular note may be the following magazines which feature stories about Cornish and his canine experiments: Popular Science (February 1935), Modern Mechanix and Invention (July 1934 & February 1935), and LIFE magazine (1934-35). The entirety of the film Life Returns can be viewed and downloaded at the Internet Archive. Footage of the actual experiment begins at around 48:25 (please note: it is not for the squeamish).

Great article. Cornish was completely new to me, though I’d seen The Man They Could Not Hang. I wonder whether Jimmy Sangster knew of Cornish when he devised the sequence in which Frankenstein revives a dead dog in The Curse of Frankenstein.

A fascinating article, Gwen. I’d never heard of Cornish, although I have enjoyed the Boris Karloff films he inspired. I am familiar with George Washington Crile, however. My novel, The Vampire Siege at Rio Muerto, features a character named Dr. Cyrus Washburn, now a washed-up alcoholic living in a desert ghost town, who was once an assistant to Dr. Crile and helped him perform some of Crile’s experimental blood transfusions. At least Crile’s work led to something beneficial, once the secret of blood types was discovered. Too bad the authorities interfered in Cornish’s work. Who know what he might have accomplished! ; )