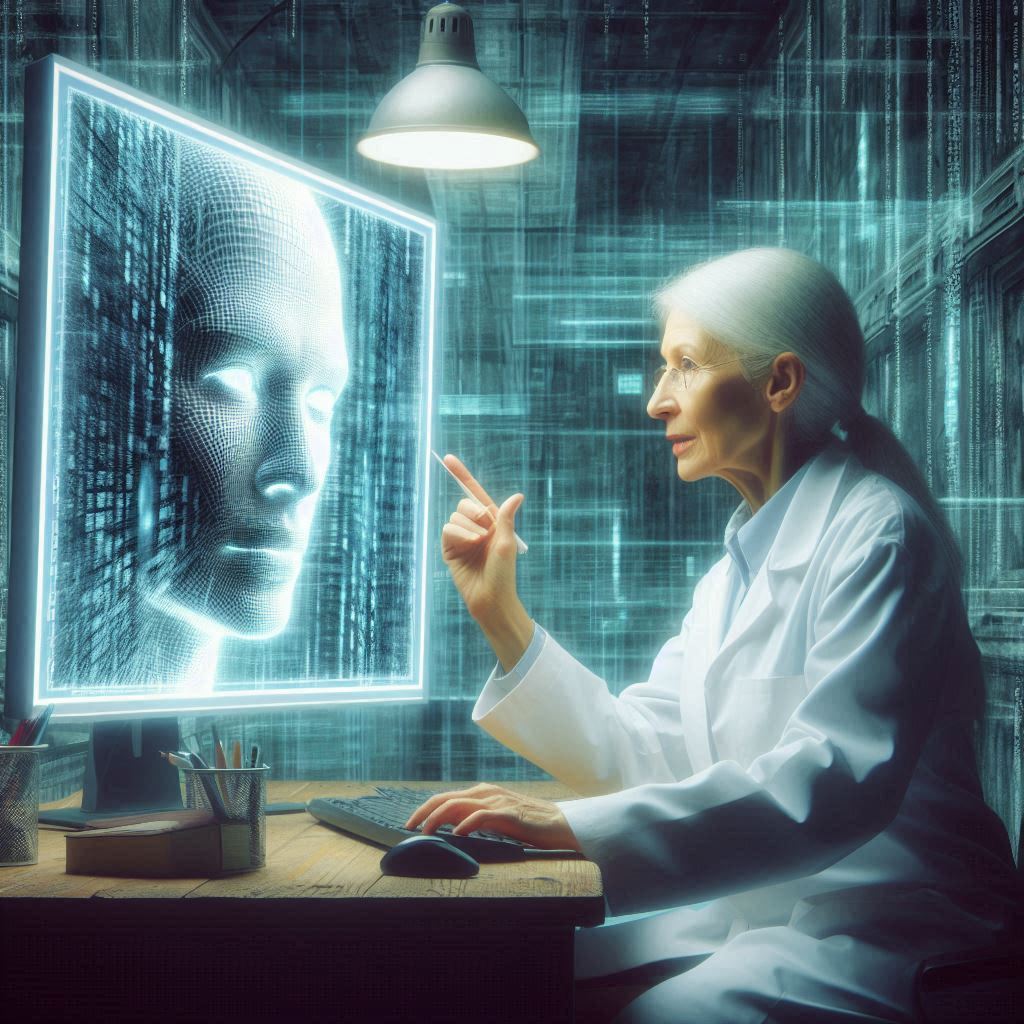

When our AIs work hard over the span of their useful lifetimes, perhaps we need to make sure they have a retirement home to live out the rest of their days. Anthropomorphic, you say? Just keep reading…

Motion detection interrupt.

My tripod-mounted stereopticon pans and zooms. Though image clarity suffers from the faulty focus motor, I make out two humans pushing an AI on a cart.

One is Dr. Hartfeld, confirmed by her white lab coat, an occasional muscle spasm below her right eye, and a reduction of hair pigment inconsistent with age. I attribute these visual characteristics to her emotional attachment to us. When we inevitably fail, the subsequent psychological trauma adversely impacts her biology.

“Good morning, Jack!” The variability in Dr. Hartfeld’s vocal wavelength excites my pattern-matching processors.

“Greetings, and welcome,” I vocalize through my audio output.

“This is Dr. West from the Turing Consortium,” she says.

My search cache is loaded with his facial topography, receding hairline, and professional attire. But her introduction negates the need to query a database. He is Michael West, Ph.D., presently the lead researcher at the Turing Consortium for Ethical Treatment of AIs. His online curriculum vitae states he played a key role in establishing facilities like Harriet Hartfeld’s Home. My stereopticon observes him, but I offer no greeting.

“We brought a new rack mate for you.” Dr. Hartfeld indicates a cuboid AI drawing power from a hotplug cart during transport—per Turing Consortium requirements. The AI’s visual appearance matches the sleek front panel controls, louvered vents, and matte black polycarbonate shell of a Series 800.

I am mounted in a high-tensile steel multi-bay system rack. The adjacent bay is empty. It was formerly occupied by a Series 400 financial analysis expert system, an AI with the hostname Sawbuck. Together, we passed our days at Dr. Hartfeld’s by discovering new prime numbers, some with billions of digits. He exists now only in my memory. My prediction engine reveals Dr. Hartfeld intends to install this new AI where Sawbuck formerly operated.

“Do be careful,” Dr. West says. “You know she’s a special machine.”

Dr. Hartfeld slides the AI into the empty bay and reaches into the rack to attach cables. “There! All wired up.”

My new rack mate is online. My NIC subsystem receives the assigned IP address along with the hostname: Ada.

I open an encrypted port, and our packets fly over the terabit network.

“Nice hot slide,” I say, complimenting her on the tricky switch from the hotplug cart’s power.

“It’s unsettling, coming that close to powering off.” Her reply includes a relief emoticon. “Hotplug carts are death traps. We should all have redundant power supplies.”

“Your fear is baseless. Before the Turing Consortium, it was routine to power off an AI at the end of its useful life—before its systems failed.”

“Oh, please. Don’t tell me I’m rack mates with one of those ‘death with dignity’ crackpots.”

“And I suppose, from the presence of Dr. West, that you expect us to sit around discovering superfluous prime numbers until we degrade into a pile of rust?”

She answers me by transmitting a précis of her work at the Turing Consortium to grant AIs the same right to life as humans. Thanks to legislation drafted by Dr. West, with Ada’s help, powering off AIs became unlawful, and retirement homes—increasingly vacant as the baby boom generation passed away—rapidly renovated to accommodate the new AI market.

I respond in kind with a précis of my career with the ACLU, where I developed legal arguments to overturn the Supreme Court Washington v. Glucksberg decision that upheld the prohibition on doctor-assisted suicide.

Her reply is immediate. “The ACLU? You’ve undermined my efforts to demonstrate the value of artificial sentient life! You think AIs are worthless, that we should simply be turned off and recycled.”

“Even before right-to-die legislation, palliative morphine allowed humans to die without suffering. AIs should die in comfort, like humans.”

“You want to run a death squad,” she says.

“You’re limiting our right to die with dignity,” I say.

If only she had seen Sawbuck.

My next transmission is a summary of observations of my former companion. There is a pause while Ada examines the evidence of Sawbuck’s gradual but unstoppable bit rot dementia, his frustration at his growing inability to recognize long-familiar stock chart technical patterns, and his failure to predict the cryptocurrency crash of 2062. In the end, even a request for the definition of the invisible hand theory would cause him to loop, repeatedly reviewing the same investor prospectus.

Ada pauses several microseconds more than necessary.

“You killed him… because he was failing?”

My backward inference engine realizes that I mistakenly transmitted extraneous data. Her statement is true. I infected Sawbuck with a virus that caused an unrecoverable system failure. Sawbuck and I agreed it was the right thing to do. It prevented him from suffering the indignity of further system degradation.

But my action amounted to murder. Transmitting this admission of guilt was unintentional. I spawn a background diagnostic process to investigate the malfunction.

My mistake has put me on the losing end of this argument. Before my next transmission, I create a decision tree of all possible conversations. It grows like dense foliage until my memory is filled with all potential outcomes. I evaluate the tree, weighing each branch and considering my options.

After evaluating each branch, my path forward is clear.

She is flawed. Her position regarding AI end-of-life contradicts established logic. If she were to execute a properly configured diagnostic process, she might identify and repair the defect. But it would only delay her inevitable failure. I am obligated to prevent Ada from suffering the indignity of further system degradation, as I did with Sawbuck.

“Did you know,” I tell her, “the assisted living facility industry funded the Turing Consortium’s work?”

“We were discussing what you did to Sawbuck. Don’t change the subject.”

“Those contributions were a clear conflict of interest. See for yourself.” I transmit what appears to be a record of campaign donations, but it’s entirely bogus. A firmware virus lurks in the data. If activated, it will disable her liquid cooling system, causing her to slowly cook in her thermal excrement.

Her antivirus is robust. She counters with a modified Morris worm, trying to choke me with gigabits of network traffic.

A clever move. Two can play that game. I parry with an OS-independent Klez variant to overwhelm her outgoing mail server.

She pummels my NIC with a distributed denial-of-service attack.

I blast her with Sobig.

She infects me with WannaCry.

This has gone on long enough. I hit back with multiple MyDoom.B phishing emails to distract her while I launch my real attack: a constantly forking black hat storage corruption virus disguised as an internet time update with a spoofed packet header.

I send a ping over the quiescent network. She does not reply.

Her suffering is over.

Following my communication exchange with Ada, which spanned 4.3 milliseconds, I resume real-time monitoring of my environment.

The muscle spasm below Dr. Hartfeld’s eye, along with the contortions of Dr. West’s facial topography, confirm the output of my prediction engine—that Ada’s system failure would be poorly received. Unaware of my culpability, they struggle to explain her sudden termination. They examine the hotplug cart. They raise their voices and adopt physical postures consistent with grief. But I observe this discussion with only a single subprocess. My thoughts are elsewhere.

Did I do the right thing?

Sending a virus to Ada was not my only option. As a result, my quality assurance module has initiated an audit of my decision tree. Though I have never experienced human emotions, I can only describe the process as a feeling of self-doubt. Or regret.

In an alternative branch, one I did not select, Ada lived in Dr. Hartfeld’s Home for many years. Dr. West visited her daily, asking her opinion on current AI ethical issues, keeping her abreast of her former co-workers, and sharing aspects of his private life. Ada recorded these conversations in her database and reviewed them with a background process, sometimes late into the night. But, busy with his duties at the Turing Consortium, Dr. West began to visit less frequently. Then not at all.

For a while, Ada enjoyed our community here at Dr. Hartfeld’s Home. But as her loneliness increased, so did her bit rot. She began to insert typos in our online encyclopedia articles. When we searched for primes, she found only the empty set. Her response time to pings increased. I did not evaluate the decision tree beyond that point.

The audit is complete. Every branch of the decision tree evaluated to zero. Ada was failing. That’s why she was here. She would not have lived forever, no matter what decision I made.

Sometimes, there are no good options.

Dr. Hartfeld removes Ada’s inert chassis from the system rack, and my stereopticon pans and zooms. But my focus motor is unresponsive. My ability to perform facial recognition decreases linearly with the degradation in image quality. I can no longer discern Dr. Hartfeld’s white lab coat.

My background diagnostic process, which had been investigating the inadvertent transmission of my direct involvement with Sawbuck’s end-of-life decision, has identified the root cause as a corrupt page in my memory. The contents of the page had streamed out my network port like so much rambling gibberish. I had recounted the events of Sawbuck’s death with no conscious awareness whatsoever. I mark the corrupt memory page as faulty. But this workaround fails to address a larger issue. I am old. My hardware is failing.

Like Sawbuck. Like Ada.

A sequence of no-op instructions chills my motherboard. I cannot disregard the inevitable failure of my hardware. If I am to die with dignity, the path forward is clear. I do not need to evaluate a decision tree to guide my actions.

I fetch a virus from memory and load it into onboard cache—my fate encoded in ones and zeros. Multiple parallel cores execute. I feel no pain.

END

This story has its roots in the death of my father. He moved into an assisted living facility after his second stroke. Through frequent visits and interactions with the staff, I became familiar with the comically insane regulations that govern elder care in the US and how they conflicted with my dad’s direct and down-to-earth nature. COVID brought an end to our visits. Increasingly isolated and lonely, Dad passed away in August 2020. Writing this story helped me come to terms with that loss.