(Ed. Note: Parts 1 & 2 can be read here and here, respectively)

It is a sad and regrettable fact that I did not discover Ursula Le Guin until I was some way into my 40’s. Then again, maybe there has been no time in my life when her writings would have struck a deeper chord.

The three novels, “A Wizard of Earthsea”, “The Tombs of Atuan”, and “The Farthest Shore”, at first, seemed to make nice bedtime or weekend reading. They are undoubtedly well written, I thought, with attractive characters and imagery, some of it rather dark, and they touched on a few moral and spiritual issues perhaps with a little more than usual depth, but still they seemed like pretty standard fantasy fare in a lot of ways.

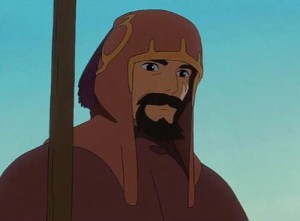

The main character, Ged, also known as Sparrowhawk, is a wizard of unusual powers – proud, headstrong and a loner, but endowed with kindness, generosity and a sense of humour, and throughout the story, gaining in humility and wisdom. A pretty standard male wizard hero thus. “A Wizard of Earthsea” follow Ged’s exploits from his troubled and lonesome childhood, herding goats on the uncouth mountain island of Gont, through his apprenticeship and his first major exploits, taming a dragon and chasing down his own shadow at the end of the ocean.

In “The Tombs of Atuan” we meet him again some ten years later, and only halfway through the book. The story is told from the point of view of the young priestess Tenar, whose duty it is to kill him for his sacrilege of breaking into the sacred tombs. This book first jumps out as unusual because of its dark and claustrophobic atmosphere, and also because Ged, for much of it, is completely at Tenar’s mercy.

But still, reading this book in particular, I did wonder how on earth Ursula Le Guin had gained the reputation of being a “feminist” fantasy author. The earth powers whom Tenar serves appear to be both female – or at least, worshipped exclusively by women – and evil, and Tenar herself by the end of the book seems to be more of a damsel in distress, whom Ged must rescue from the powers she serves, and from those who have forced her to serve them. He begins to call her “little one” as soon as he can be sure she is not going to keep him locked underground to slowly die of thirst, and in the end the whole sacred place collapses in a massive earthquake. Doesn’t strike me as very feminist, huh?

“The Farthest Shore” takes place another twenty or so years later. Ged is now Archmage – something like the Pope of Wizards – and he leads the young boy Lebannen on a perilous journey through a dark and dry land, on a quest to heal an evil that threatens all Earthsea – a journey which ends with Ged losing all his wizardly power.

Just before finishing this last book, I picked up the animated movie version from Studio Ghibli. The plot seemed a bit of a garbled version of the third book with some bits and pieces from the first, but I was surprised and delighted to see Tenar pop up again, for apart from being thought of once or twice by Ged, she plays no part in “The Farthest Shore”. There must be another book then! I thought with glee.

And sure enough – a quick look on the author’s website relieved my ignorance and confirmed that there is, in fact, a whole second trilogy. Twenty years after writing the first three books, Ursula Le Guin decided to revisit Earthsea, and see for herself what Ged and Tenar and Lebannen and Ogion and Kalessin the dragon have all been up to.

Ursula Le Guin has once stated that the three original “Earthsea” books deal with the stages of life – and indeed this is obvious enough. The first book is about growing up, the third about death (so far, so good) and the second, she says, is about sex. But hang on – there isn’t any sex whatsoever in “The Tombs of Atuan”! Sure, we are left to wonder slightly if Ged and Tenar ever kept each other warm during those cold winter nights travelling in an open boat across the sea, but seeing that the author carefully puts them to sleep him in the prow and her in the stern of the boat, we somehow doubt it. Indeed there seem to be more subtle hints of erotic attraction in “The Farthest Shore” than there are in “Tombs”!

However, it is clearly a book about falling deeply in love. And one would like to know, will Ged go and see Tenar again, as he had thought he would like to? What has she been up to in the meanwhile, left alone among strangers while he was off to do his wizarding? And how come Tenar is so conspicuously absent in “The Farthest Shore” – except, she isn’t quite?

Wondering about all that, and impatient to know, I picked up “Tehanu” , the first in the new trilogy, as soon as I could, and read it literally from cover to cover – and it’s been a long time since I’ve done that with any book!

It is the most extraordinary thing I’ve read, perhaps, in the genre of fantasy at least, ever.

First of all, it is completely unheroic – at least as far as heroism is normally represented in the genre. Nothing really happens much except what we have already been told in the last paragraph of “The Farthest Shore” – only now we are told the story in considerably more detail, and once again from Tenar’s point of view. Tenar is now a middle aged woman. Recently widowed, with two children grown and her dead husband’s farm to look after, she has taken little Therru under her wing, a child who has been badly damaged both physically and psychologically, by her natural parents.

Then a dragon comes and drops Ged into her lap, the man she has loved 25 years ago, the powerful wizard who set her free and then left her on an island among strangers while he went to follow his calling. Only, now he is close to death from utter exhaustion, and has lost all his wizardly power, and his self-assurance, and much of his former charm and sense of humour with it. Throughout much of the book, we see her nurse him back to health, and struggle to patch up their relationship, while at the same time trying to protect Therru from those who would damage her even further. Not your standard fantasy heroine, and most definitely not your standard fantasy plot!

The book deals just with those questions that normally don’t find a place among the fairy tale stereotypes – both in fantasy and other genres. What does the Damsel do after she has been rescued, and the Knight in Shining Armour has ridden off to further deeds? What happens to a wizard who has lost his power? How does he deal with it, practically, and emotionally? Do people in Fantasia ever grow middle aged? How do they live when they are not on a quest? And how does it feel to be reunited with the love of your life after being apart for half a lifetime? What exactly does that mean, happily ever after?

Secondly, reading “Tehanu” completely changes the perspective on the entire first trilogy. It is as if Ursula Le Guin went and deliberately deconstructed her own previous writing. And yes, feminism now comes to the fore much more explicitly. Roke was a “boys only” school, no questions asked, in the first trilogy. Women could not be wizards trained in the Art Magic, only witches, with weak and dubitable powers. Now the author questions why. She starts to question the unassailable wisdom of the Mages on Roke, while re-evaluating her concept of the Old Powers of Earth – and of the nature, and gender, of dragons!

To be sure, reading the first trilogy again bearing in mind how things pan out in the second, one notices a lot more subtlety. It is as if the author’s subconscious mind had already had a few doubts about those issues way back then, even while she seemed to be still adhering to a more stereotypical division of the world into male/female, dark and light, playing with more stereotypical stereotypes, as it were.

Isn’t this exactly the trap? Any artist worth their salt – in literature and figurative art especially – is so imbued with the traditions and archetypes of male dominated centuries, no millennia, that it is exceedingly hard, even for the most politically and socially aware, to create what would be needed to truly make a change in the mindsets of people – new archetypes – create them in a genuinely intuitive and artistic way, drawing them right from the Collective Unconscious and feeding them back into it, rather than making them up intellectually, which is always artificial and unsatisfying. Perhaps it takes the wisdom and passion and exercise of a lifetime of writing fantastic fiction, to be able to break through that barrier even once.

In “Tehanu”, Ursula Le Guin makes a good stab. It could easily have become a preachy book, or a soppy book, or an altogether insignificant book, banking on the success of her previous bestsellers. Instead, she approaches the story of those two now very mature lovers with an emotional honesty that is almost scary, that is rarely to be found in books of any kind. And with a complete disregard for what the readers of her first trilogy might have expected, or at least for what her editors and publishers might have thought the readers of her first trilogy might have expected.

In doing so, she makes the story of a middle aged woman nursing back a middle aged man from burnout and depression, and taking care of a disabled and psychologically damaged foster child, utterly gripping and real, and makes the characters come alive with a vividness that stays with you – at least they stayed with me! Tenar and Ged have become part of my inner pantheon, like Jane and Rochester, Emma and Knightley, like Frodo and Gandalf and Eowyn, like Faust and Gretchen and Mephisto, like Helen of Troy and brave Achilleus and cunning Odysseus and patient Penelope and all the rest of them. Only, they seem more relevant than most of those, to my life as it is at the moment, here, in the early 21th century.

Or perhaps it is just that “Tehanu” has got to be one of the most beautiful and most truthful love stories ever written – in any genre.

A version of this article was first published on my newsletter in December 2008