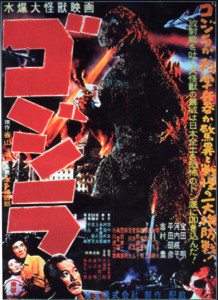

There are but a few good things to be said about the new Godzilla. The best thing to be said is that it inspired a theatrical re-release of the original, Raymond Burr-free Japanese version from 1954, which I had the pleasure of seeing last week. I’d seen it once before, ten years ago, during its last theatrical resurrection (in glorious 35mm, back in them thar olden days of ’04), and even further back in the day, when I was but toe-high to a prehistoric radioactive lizard-thing, I saw the Americanized, Raymond Burr-ful version, known as Godzilla, King of The Monsters! any number of times on channel 44. Or was it channel 20? (Oh, the days of UHF.)

My current verdict: all kinds of awesome! Sure, it’s a bit slow and dopey now and then, and the man in the Godzilla suit looks exactly like a man barely able to move in a Godzilla suit, but its strengths far outweigh such quibbles.

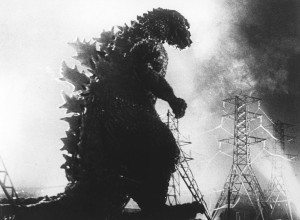

It’s shot almost like a film noir. Lots of shadows, looming dread, a slow build. Godzilla’s first appearance rising up behind a hillside is weird and scary. I don’t think his face ever looked better. You almost want to take him home with you. But then he’s howling and breathing radioactive fire on your car, and everybody dies.

The movie does not shy away from parallels with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. One scene I’m sure was cut from the American version has a man and a woman riding a train, casually discussing this giant monster from the sea looming off the coast. She says, breezily, “I survived Nagasaki, I can survive Godzilla.”

Godzilla is presented as a monstrous metaphor for an H-bomb. He leaves crackling radioactivity in his wake. Scientists from the start presume H-test to have awoken him. Worst of all, if all the bomb did was wake him up, what would it take to kill him?

Godzilla lays waste to Tokyo in the movie’s central set-piece. The entire city burns, just like in WWII. A panning shot of the attack’s aftermath, the city leveled and smoking, is designed to look just like Hiroshima. And in one village through which Godzilla stomped, the children are left irradiated.

Godzilla is very much the embodiment of nuclear fear, the necessary result of having unleashed such horrible power into the world. He’s nature’s revenge on humanity. He may be the bad guy, but we brought him on ourselves.

The movie opens with fisherman on a boat seeing a blinding flash of white light. Something bubbles up from underneath them, blasts their ship with flames, and sucks them below. Writer/director Ishiro Honda based this on an incident in March, ’54, where a Japanese fishing boat was hit with nuclear fall-out from a U.S. bomb test on Bikini Atoll. Critics of Godzilla in Japan, and there were many upon its release, faulted it for cheaply playing on this incident, and for its use of imagery meant to evoke the atomic destruction of WWII.

Not that such criticism mattered. The movie was a hit. It’s spawned 27 sequels, even though Godzilla is killed in the original. Those other Godzilla movies? Same species, different Godzilla. They mention the possibility that more of them could be out there, and that further screwing around with H-bombs might wake them up. But did we listen? Nope. We woke up another one. If I knew my Godzilla history, I’d know if he died in any other movies. Have we only ever had two Godzillas? One in the original, and one stomping his way through the sequels?

Godzilla is killed by a scientist, Dr. Serizawa, a sweaty, eye-patch-wearing weirdo, who’s secretly designed a weapon, the Oxygen Destroyer. His one-time fiancee, Emiko, is the only one who knows about it, but she’s been sworn to secrecy. After witnessing Godzilla laying waste to Tokyo, she reveals its existence to her new boyfriend, Ogata. He and Emiko beg Serizawa to use the weapon to kill Godzilla.

The Oxygen Destroyer sucks all oxygen from water, killing anything alive, then liquifies their bodies, leaving only bones. He gives Emiko a demonstration in his fish tank. She screams and cries, because, you know, fish skeletons.

Anyway, Serizawa won’t use his weapon. He knows politicians. He knows people. They’ll use his weapon to wage war. Even if he destroys his notes, the knowledge will remain in his head. Stopping Godzilla isn’t worth putting another doomsday device in humanity’s hands. And yet, in the end, he relents.

On a boat in the sea, Serizawa insists on activating the device himself underwater. He and Ogata don diving suits, their air supplied by hoses, and swim around until finding the sleeping Godzilla. Serizawa activates the device. Ogata surfaces. But not Serizawa. He slices his oxygen hose. He won’t allow his Destroyer to ever be used again, even at the cost of his own life.

Not like that bastard Oppenheimer, in other words.

The last we see of Godzilla, he juts up from the water, howling his Godzilla howl (best monster voice of all time? yes), and plunges down to the bottom of the sea, a skeleton.

In future Godzilla movies, Godzilla develops much more personality. He winds up a good guy most of the time. He makes up his own dance move. In the original, he’s something shadowier and more primal. He’s almost only seen at night, often just his head, thrashing around in the ocean. He’s a reminder that human hubris comes at a cost.

This article originally appeared on the cinema blog Stand By For Mind Control, where editors Sean McPharlin (aka the Supreme Being) and Zack Kushner (aka the Evil Genius) cover the breadth of cinema in their inimitable style. They are thrilled to be contributing discussions of genre cinema to Amazing Stories.