No one has ever mistaken me for an intellectual. Mind you, in my teenage years when I went around calling myself the world’s greatest pseudo-intellectual some appeared to consider that plausible, if a bit presumptuous. Nevertheless, I occasionally had a thought, or at least I used to back in the day.

Earning my Bachelor of Arts degree at the University of British Columbia put my brain to a test. Could I get it to work or not? I had the feeling my marks depended on my ability to think. Day dreaming might not be enough.

I very quickly learned that ignorance can be disguised with false sincerity (politicians instinctively know this) especially, in a university setting, by insistent bafflegab within a false context entirely separate from the reality of what you’re talking about (film and theatre critics instinctively know this).

Case in point, the necessity of choosing at least one English literature course in order to fulfill the requirements of my curriculum. I was majoring in Creative Writing, with Theatre courses thrown in because I wanted to learn about character motivation. (I didn’t.) I chose a course entirely devoted to the writings of D.H. Lawrence.

I hate the writings of D.H. Lawrence. Always have.

Or at least I hate his fiction. His travel writing is superb.

But the course I picked was titled “The Classical and Biblical Background to the Novels of D.H. Lawrence” and that was something I could sink my teeth into. A strenuously meaty conundrum to resolve. It would be fun. And it was.

The final course exam (as I recall) consisted of two parts.

First, a lengthy poem by Lawrence which I had never read. Task? To explain the symbolism. Bummer.

Then I realized it was based on the myth of Europa, or Persephone, or somebody. Can’t remember now. But at the time I knew the myth underlying the poem very well indeed, and promptly whipped off four pages of interpretation. Got a good mark for that. It helps to bluff. Believe me.

The second half of the exam posed a problem. There were four essay topics. I only had to choose one, but I didn’t like any of them. Bummer again.

Suddenly I remembered the Professor had commented during our last class that if we didn’t like any of the essay topics we should make up one of our own. Huzzah!

So I unleashed my subconscious mind and wrote out ten pages comparing D.H. Lawrence’s writing technique to Salvador Dali’s ‘Paranoiac-Critical’ method of painting.

I got a very high mark for this.

And on the paper, the written notation:

“This almost makes sense!”

Wish I had kept it. It may have been the best thing I ever wrote. Oh well. Lost to the mists of time.

Point is, I was well exposed to the academic style of writing (and thinking for that matter).

I respect University. I loved University (it was a wonderful escape from the real world), but I can’t abide novels, films, reviews or nonfiction books created by academics for the sole purpose of impressing other academics. They suck.

For example, if a book on archaeology or ancient history is written with the general public in mind, it is fast paced, full of interesting detail and amusing anecdotes, and so darned interesting it earns an honoured position on my shelf and is read and reread frequently, say once every two years or so.

But if it is an academic treatise masquerading as something the general public should read, it’s invariably dry, boring, and so filled with caveats, hesitant interpretation and timid conclusions I can hardly wait to toss the meandering, gutless mess into the garbage. Yet academics tend to snear at populist authors and accuse them of pandering to the masses.

Well, I like being pandered to. Simple as that.

You may have noticed by now I have a bit of a ‘thing’ about the inadequacies of academic interpretation as a form of communication. It’s one of the pet bugaboos I go on and on about at the drop of a hat.

One day, after I graduated, and was trying to describe the joys of the film ROBOT MONSTER to a friend I’d made at University, a friend perfectly familiar with my phobia re: academic writing, he unexpectedly said:

“I dare you to write an academic paper on ROBOT MONSTER and make it interesting. Bet you can’t.”

Well, I took him up on his dare, but not wanting to fool around with footnotes and citations and such, I wrote a straightforward ‘spoof’ of an academic treatise which I then published in my first fanzine ENTROPY BLUES in 1986. I present it here for your delectation.

But first, a brief synopsis of the movie’s plot:

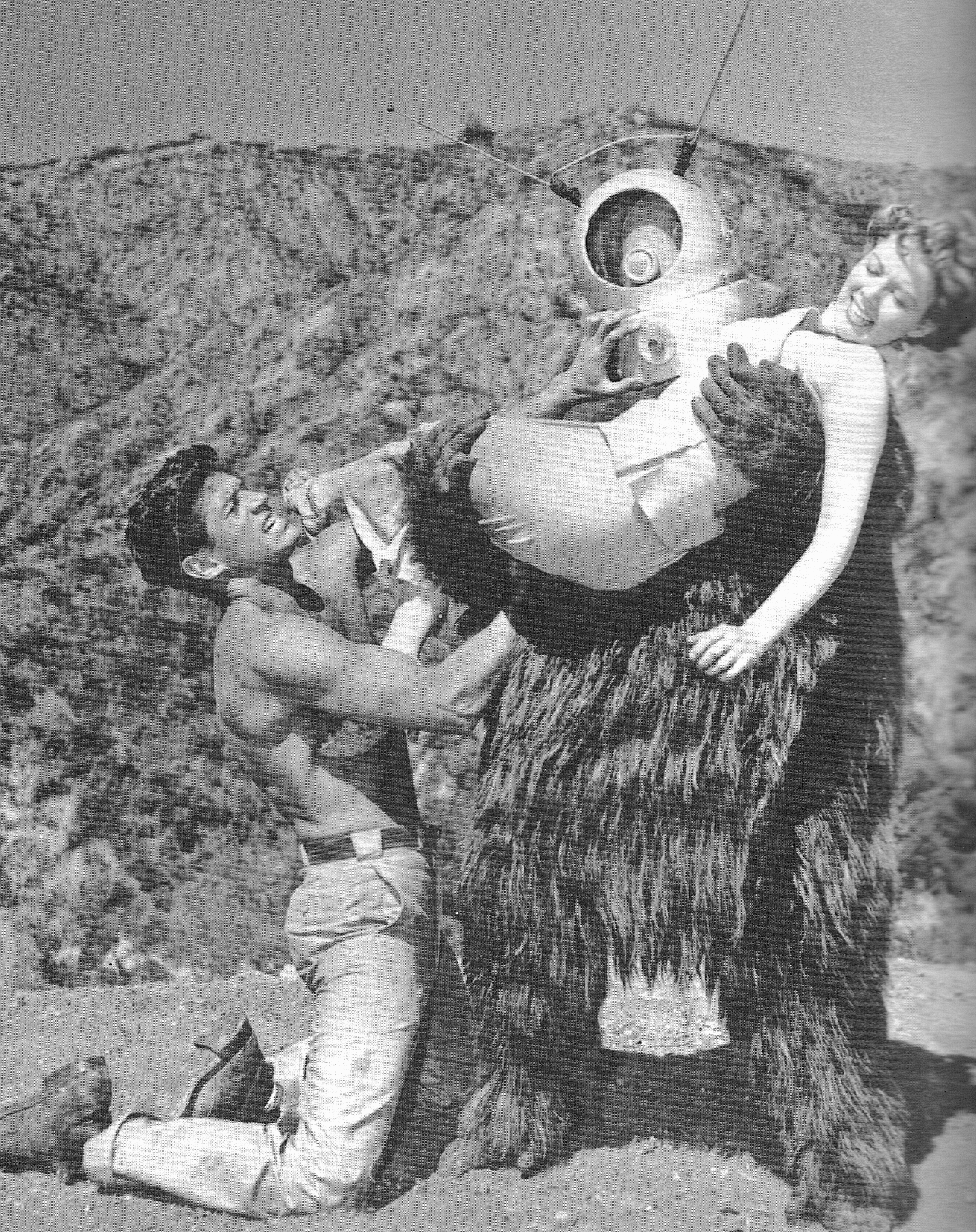

This 1953 film begins with the evil alien robot monster RO-MAN having already wiped out most of the human race with his Calcinator Ray. He learns there are a few HU-MAN survivors hiding nearby. Politely, he requests they come to him so that he can kill them. They refuse. In the course of hunting them down he learns that one of them is a WO-MAN. He becomes obsessed with the task of ‘unification’ with her, but his Commander, the GREAT GUIDANCE, wants him to carry out his extermination mission and not waste time with frivolities. For perhaps the first time, RO-MAN begins to question his purpose in life. No good can come of this.

And now:

THE MEANING, MESSAGE, AND SYMBOLISM OF ‘ROBOT MONSTER’ – AN INTERPRETATION

Let us consider the symbolism screen-writer Wyott Ordung employs, keeping in mind that his themes is the conflict between reasoning man and emotive man, and where this struggle may ultimately lead us.

Note the subtle structuring of the cast. The HU-MANs consist of three couples: two children, two young adults, and two elders. Here we have the three stages of human sexuality, the basic paradigm of all that is human. These allegorical figures represent innocence, youthful vitality, and learned wisdom. In sum, the best the human race has to offer.

And then there’s RO-MAN, representing the monster conflict which threatens humanity, that basic split in our psyche, our Apollonian/Dionysian dichotomy, which is illustrated by the contrast between RO-MAN’s robot aspect (metal helmet, antennae, face hidden by a blank white cloth) and the beast aspect which his obscenely shaggy body amply demonstrates.

Wyott Ordung speaks to us all when he poses the problem: can we destroy the monstrous wound we have ourselves created?

Consider innocence as a weapon, or at least as a form of defense. The boy often escapes because he can outrun the ponderous RO-MAN. Yet we all know that to deny the reality of danger through the ignorance which innocence offers is an illusionary form of safety at best.

Ordung is quick to prove this in what must be the most callous and brutally shocking moment of violence in cinematic history. (You think the shower scene in PYCHO was the worst? Read on.) RO-MAN confronts the little girl walking alone on a barren hillside.

“What are you doing here?” he thunders.

The girl stares defiantly up at the alien and replies:

“I’m not afraid of you. My daddy won’t let you hurt me.”

Ah, the sweet trusting innocence of childhood.

The RO-MAN lunges for the girl. We do not see her death. It is not necessary that we should. The idea suffices.

The scene alludes to the loss of innocence we’ve all shared, the end of childhood, the entry into the adult world of sexual passion, the eternal adult problem of uniting mind and body in a coherent whole, a problem made more difficult by the growing power of the RO-MAN within us all.

Wyott Ordung warns us innocence is not enough. Innocence is fatal.

Perhaps we can turn to learned wisdom? To the rational mind warmed by experience and calm, civilized, humanitarian consideration? The Professor has witnessed the destruction of the human race, yet believes RO-MAN will spare the few who remain if they can prove they are not a threat to him.

What an idiot.

Naturally his efforts to placate RO-MAN place his family in even greater danger.

This is perhaps Ordung’s wryest comment on human progress.

Wisdom is a form of innocence and just as fatal. At best we might influence our Apollonian aspect, but the realm of Dionysius is beyond common sense, beyond rational awareness. The best of what we have become is ineffectual in the face of the worst of what we’ve become. Paradoxically, our growing sanity is but a symptom of our developing psychosis. Bold of Ordung to point this out.

So the future lies with youthful vitality, with the lust for life, and above all, the power of lust, which solves so many problems in so many films? Only a mixture of innocence and wisdom fired by enlightened human LUST can save us from the egalitarian ant-mind nightmare of the RO-MAN?

Alas… No.

As Ordung and Director Phil Tucker clearly demonstrate.

First, they take great pains to establish the essentially innocent power of the young couple’s sexual fervor, as in the TV repair scene, her hand on his, guiding his turgid soldering iron gently within the electronic components, saying:

“No, not like that… That’s right… Ohh, yes!”

Ironically, their initial attempt fails. Do they give up? No. Consider the man’s inspired comment:

“Don’t you realize, it’s impossible? But you almost did it!”

(Perhaps the best piece of dialogue illustrating man’s eternal optimism ever recorded on film.)

However, all this lust is doomed, for just as the Professor fell prey to the inhuman Apollonian robot-mind of RO-MAN, his daughter succumbs to the raw Dionysian power of RO-MAN’s animal body. Her sexual excitement on volunteering to meet RO-MAN alone is so obvious her entire family wrestles her to the ground and ties her up. Later, when the powerful RO-MAN succeeds in carrying her off, her patently phony screams, delighted smile and half-hearted kicks reveal how pleased she really is.

Will she tame the monster conflict? Heal the wound?

No, for the lustful RO-MAN is repeatedly called away from the great experiment of unification (which he is as eager as she to attempt) by demands from his leader – the GREAT GUIDANCE – (read: the mind desperately seeking control) for information on what is going on.

Ultimately, she is rescued, and RO-MAN experiences enormous frustration as any personification of humanity’s greatest internal conflict rightfully should. Alas, when RO-MAN learns the power of lust is useless, a chain-reaction of doubt and confusion is triggered in his mind, his two aspects warring. Ordung’s subtlest manoeuvre, the image of the problem experiencing the problem it represents, a lesson for us all.

As a final consequence of the dilemma, the GREAT GUIDANCE destroys the Earth and everything on it by unleashing a ray which runs time backwards, spawning dinosaurs, etc., until nothing remains, for it has not yet formed.

Ordung’s sly hint we still have a chance? Let us hope so.

By showing us what won’t work, Ordung and Tucker urge us to find out what will work, stimulate us to survive. Truly, a message for our time.

Director Phil Tucker, in reflecting on the significance of ROBOT MONSTER, stated years afterwards:

“For the budget, and for the time, I felt I achieved greatness.”

< — >

Having provided the above essay for your consideration, I leave you with the following thought:

IT ALMOST MAKES SENSE!

(Editor’s Note: If you’d like to pen your own academic polemic on this film, you can start by watching it here)

A master’s thesis on Robot Monster? Wow! That blows me away. I’m impressed. Script Writer Wyatt Ordung and Director Phil Tucker would be proud.

To me the only truly ‘bad’ film is a dull, uninteresting, boring film. Robot Monster is genuinely entertaining, though perhaps not in the manner Ordung and Tucker intended.

Besides, in the context of its time, it was up to the standard of many a cheap grade z non-genre movie. Tucker (and Ed Wood Jr.) didn’t operate in a vacuum (a point often forgotten today when their work is routinely, and wrongly, compared to the best films of their era instead of the worst) but touches of originality (to put it mildly) mafe their films leap out of the screen. Once seen, never forgotten.

Agreed!

Enjoyed this, thanks. Interestingly enough, my good friend Jeff Sconce wrote his masters thesis on Robot Monster! He and I were connoisseurs of the art of the “bad film” back in the day. Jeff is now a tenured professor at Northwestern, still subjecting young minds to “questionable media”. If Ro-man only knew…