Planets – most of them fictional – are among the most interesting subjects of SF and sometimes the real protagonists of novels. Getting them right is essential, and it starts with their names. Easier said than done. It’s like naming your pet or your own child, with the difference that with planets you have a few more constraints – such as originality, for instance. Some names are worldwide famous – think about Tatooine – others are as obscure as exoplanets in faraway systems (who remembers LV-426? Incidentally, it is where the movie Aliens takes place). Analysing and comparing these fictional planet names, let alone trying to guess the reasons why they have been given a specific moniker, will probably take a book (even though would be an interesting one to write). Some examples will help shed some light.

One of my first memories is Asimov’s Lagash (Nightfall), a place where a day lasts two thousand years. Long enough to convey the idea of duration, and its name gives some hints: Lagash was one of the earliest cities in Mesopotamia, in Sumerian times, about 3000 years old. This illustrates something common in SF: you can often guess planet features from their names. Geographical and cultural references abound. Trondheim (Speaker for the Dead, Ender’s Game saga, Orson Scott Card), named after the cold city in Norway, seems just right for an icy planet, and so it’s Lusitania, colonised by Brazilian settlers.

Shin-Tethys – from Stross’ Neptune’s Brood – sounds most likely a place where sea plays an important role (Tethys was the Greek sea goddess, wife of Oceanus). And indeed it is, with its deep ocean. Hydros (The Face of the Waters, Robert Silverberg; from udor, Ancient Greek word for water) and Thalassa (The Songs of Distant Earth, Arthur C. Clarke; fromThalassa, yet another Greek sea goddess) are other similar cases.

References to the Greek Mythology are a popular hunting ground. Atlantis (The Night’s Dawn trilogy, Peter Hamilton, ) is opportunely covered in water with only floating islands on its surface. It makes sense if you remember the lost continent of Atlantis. Staying into the Night’s Dawn’s universe, more puzzling are the two Saturn’s Edenist habitats – sort of artificial, sentient planets – which are named Romolus and Remus like the two mythical founders of Rome. (Why so, it beats me).

Another interesting case is Revelation Space (Alastair Reynolds), featuring real stars and their original names – unsurprisingly, considering he worked for the European Space Agency before pursuing a full-time writing career – but with fictional planets. You can find the neutron star Hades (the Greek Underworld) conveniently orbited by Cerberus (the three-headed dog guarding it). And Resurgam, another planet in the same star system, comes from the Latin verb resurgere (i.e., rising from the dead).

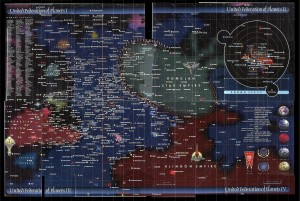

Finally, if you look at Star Trek’s catalogue, you will find a pretty detailed classification system. Close enough to the exoplanets discovery so far to wonder why nobody has proposed its adoption in astronomy.

In any case, should you wish to give a planet a name (and have neither the time nor the patience to write a SF novel) there is now a possible solution. On July, 9, 2014 the International Astronomical Union (IAU), together with Zooniverse, has invited people to submit their bid “to give popular names to selected exoplanets along with their host stars.” Around 300 planets are included in the initial list, and the rules are clear and simple.

Go to the NameExoplanet website and register (individuals are allowed too): it promises to be fun.