OBIR: Occasional Biased and Ignorant Reviews reflecting this reader’s opinion.

The Assaults of Chaos: A Novel about H.P. Lovecraft – by S.T. Joshi

Published in 2013 by Hippocampus Press, New York, NY, USA.

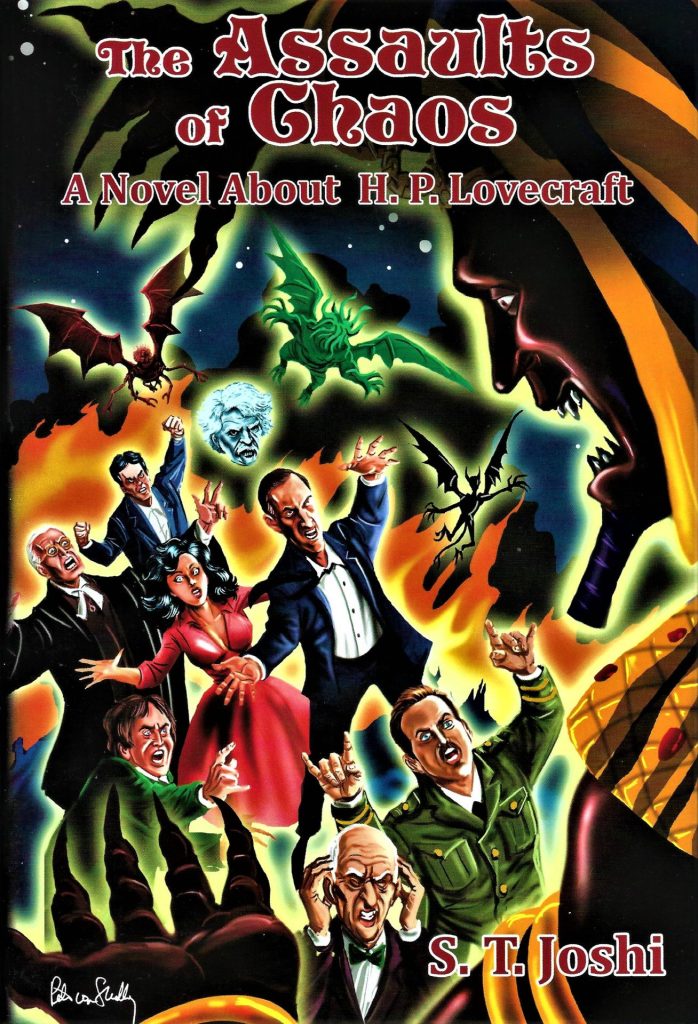

Cover art – by Pete Von Sholly

Premise:

Much to his surprise, a twenty-three-year-old H.P. Lovecraft is contacted by his long-dead father and invited to go to England to combat an unspeakable, indescribable, execrable horror of utter malignity and not-niceness.

Review:

First, an apology. As someone who’s retirement hobby is to promote Canadian speculative fiction, I’ve long had a policy of reviewing only Canadian books and magazines. However, now and again a non-Canadian book comes to my attention which excites me and occupies the space of “must-have-immediately” on my bookshelves. As a life-long fan of both Lovecraft and his writings, The Assaults of Chaos meets that criteria.

However, my apology is directed not so much at my readers as those patient Canadian authors who have been waiting to climb out of the backlog of books and magazines I’ve promised to review. Sorry. Having read this book in one sitting the day it arrived in the mail, I can’t resist a selfish surge of self-indulgence. One of the perks of being a reclusive hermit staring at the uncut lawn in the front yard. (A subtle hint as to one of the reasons why Lovecraft appeals to me.)

Second, I should address his racism. Here’s the thing. Lovecraft is noted for being oddly bizarre and startlingly unique. His racism is not part of that reputation. His style of racism was and is as common as dirt, inspired by a school of philosophy which assigned human beings to a hierarchy based on commonly-accepted anthropological definitions of cultural character. It was a universal world view expressed in thousands of books and magazines, many of them scholarly publications, and taken absolutely for granted in his day as “scientific” knowledge.

Lovecraft’s racism was entirely casual and something he automatically accepted as common sense truth, any argument to the contrary being viewed as nonsense typical of radical extremists. Often, for him, it was a source of humour. And certainly useful for creating the ambience and atmosphere around “degenerate” species in his fiction. Intellectually, though, he was ahead of his time in that he sometimes worried about “proper Americans” being replaced by “inferior” immigrants. Perhaps that just means that the “replacement theory” in the news today isn’t as “new” or “modern” as we think it is.

Be that as it may, the racist component of his character was something he literally shared with millions of other people and was neither unusual nor unique. If anything, he can be accused of being pathetically unimaginative and imitative in following what was, in his time, a populist viewpoint. An accusation that would have horrified him, being a self-proclaimed elitist who held himself above the uneducated herd. At any rate, to him, his racism was an incidental and minor aspect of his life, hardly worth mentioning.

Today, his racist writings are a vivid and powerful educational tool illustrating how far-too-many people thought back then and why we should never turn the clock back. No such thing as “the good old days.” What we need is progress, not backsliding. But enough preaching on my part. Point is, he was what he was, and he was far more than a run-of-the-mill racist. He remains the biggest weird-fiction influencer of the twentieth century, as significant as Edgar Allan Poe was in the nineteenth century. And, above all, he remains an utterly fascinating and unique character in his own right.

It is Lovecraft the character, and not Lovecraft the racist, that Joshi makes the focal point of his book. In so doing he accomplishes the feat of explaining and revealing the literary Lovecraft in all his complexity such that, having read the novel, you will come away with a good understanding of what Lovecraft thought life was all about. Joshi summarises a lifetime of research to capture the mood and spirit of Lovecraft. He does this in four distinct sections.

First, four chapters outlining the formative influences on his life, ranging from his discovery of astronomy at the age of twelve, which gave him an appreciation for the outlying endless void of the cosmos, to the dreadful, smothering attention of his mother, who never forgave him for not being born a girl and who shunned any demonstration of physical affection such as a kiss or a caress. Ultimately, astronomy was his biggest disappointment. He sucked at math, and was consequently never able to become a professional astronomer. He never forgave his own inadequacy in that matter. Amazing that he even noticed, given the layers of inadequacy his mother spun around him as a sort of maternal cocoon cutting him off from the world outside their house.

Reference is made to the attic full of eighteenth century books he explored as a sickly child. If anything, I think Joshi should have emphasised this more, since it is the basis of Lovecraft’s “natural” affinity for eighteenth century thought and writing, one of the fundamental core values of his intellect and interests. It was more than mere affectation. Let me quote from a September 1931 letter he wrote to August Derleth:

“I think I am probably the only living person to whom the ancient eighteenth century idiom is actually a prose and poetic mother tongue… the naturally accepted norm, and the basic language of reality to which I instinctively revert despite all objectively learned tricks. To others, Georgianism is an elegant pose. To me, it is the natural, subconscious thing—other styles being the artificial acquisitions.”

He goes on to say that he read numerous eighteenth century works on grammar and versification and absorbed them all by the age of twelve, and that this, combined with long rambles and bicycle rides outside Providence exploring the then numerous surviving colonial farmhouses and out buildings, not mention village churches, left him with the impression that modern works were the delusion, colonial relics the reality.

He also read bound versions of the Spectator, Tatler, Guardian, Idler, Rambler and other magazines, works by Pope and Dryden, translations of classics, dictionaries, encyclopedias, books on rhetoric… all dating from the eighteenth century. This was his formative reading at a very young age.

Me? I was reading the Hardy Boys, Tom Swift Jr, Tom Corbett, Space Cadet… somehow I don’t think I’m in the same league as H.P. Lovecraft. But it is now clear to me why Lovecraft was so enamoured with eighteenth century New England. It, more than anything else, felt like home to him.

As a teenager, he blossomed a bit, if only to get away from his mother. He became a cherished member of the Blackstone Military Band, able to play a zobo, a sort of brass horn harmonica if you can imagine such a thing, while simultaneously drumming and working a mechanical triangle-beater with one foot and cymbals with the other, all with a marvelous sense of timing. “Years later he concluded that he would probably have made a pretty good general-utility man in a jazz band.” Not the sort of image normally conjured up when people think of Lovecraft.

He had many friends as a teenager. They built a secret cabin in the woods, formed their own detective agency and wandered the streets searching for desperadoes whose mugs they’d seen displayed in the post office. Pretty imaginative I’d say. Lovecraft carried a genuine revolver in his pocket, albeit unloaded. Good thing they never caught anybody. At any rate he did in fact lead a fairly normal life as a teenager, complete with socializing and enjoying most of his High School classes. Not the fearfully shy freak of legend. Not at all.

Now we come to the second section, in which Lovecraft falls in love with Kat Banigan, loses his virginity at the age of seventeen, and crumples in the face of his mother’s disapproval. What? I ran to the index of Joshi’s massive two-volume I am Providence biography of Lovecraft. No such person listed. I wasn’t surprised. Lovecraft wrote so little of sex it’s hard to imagine him ever losing his virginity. So quite amazing to see him described in, not one, but several awkward love scenes in the course of the book.

In a postscript Joshi confesses that he made up Kathleen Banigan’s character. Lovecraft was in fact friends with two of the three Banigan brothers, and it is known they had two sisters, but not even their names are recorded for posterity. So why is this fictional character present? Joshi points out that Lovecraft’s wife Sonia H. Greene once remarked that he had told her “that his sexual feelings had been at their height when he was eighteen or nineteen.” That being so, it is entirely possible he could have fallen in love and let nature take its course. So, why not create a strong, wilful love interest to contrast with Lovecraft’s vacillating tendency to overthink everything, to serve as a useful ally in the battle to come and, most importantly, demonstrate his mother’s baleful influence over his goals and desires? Helps elucidate his character, Kat does. Her presence entirely justified.

Oh, and for the curious, Sonia also once described Lovecraft’s performance as a lover as “perfectly normal and perfectly adequate.” At, least, that’s how I remember the quote. It was finances that broke up the marriage, or lack thereof. They remained on friendly terms till his premature death. That says something.

Now we come to section three, the most delightful part of the book from my perspective. Some might find it a bit repetitive and boring, but not I. One by one the supporting cast of characters in the great battle are introduced, authors all. They each merit a chapter of their own. They are, in sequence: Ambrose Bierce, Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett A.K.A. Lord Dunsany, Arthur Llewelyn Jones Machen, Algernon Blackwood, Montague Rhodes James, William Hope Hodgson, and Edgar Allan Poe!

These are all weird fiction writers and all greatly admired by H.P. Lovecraft. He frequently dreamed of meeting them, but never had the money to travel to England. Mind you, Bierce and Poe were American, but quite dead by the time Lovecraft was twenty-three (to put it mildly). No problem in a work of weird fiction, of course. Lovecraft’s positive opinion of these gentlemen can be found in his famous essay Supernatural horror in literature.

Now, I’ve read some of Bierce, most of Poe, and virtually all of Hodgson (I’m a huge fan), but nothing by Lord Dunsany, Machen, Blackwood or James. So I particularly enjoyed the chapters devoted to those four, as they gave me a much better idea of what they were all about and why Lovecraft admired them. Though, to be fair, he had reservations and criticisms to apply to all of them. He was not slavish in his devotion.

In their respective chapters the authors’ appearance and mannerisms are described, a bit of their personal history, useful quotes provided, and quite a bit about their writing technique, and motivation, mostly in the form of discussion which I strongly suspect reflects the actual style of their writing. Lovecraft says little, but when he does his more experienced peers stand in awe of his insight and perspicacity. (Little bit of stylistic influence there… didja notice?) All in all, a wonderful introduction to these famous writers.

Funny thing, some of these people were evidently bounders, or at least distinctly odd, not to mention boastful, self-centred, rude and tactless. Takes all kinds to write weird fiction, I guess. Even odder, after reading these chapters I find myself reluctant to explore the writings of the four guys I haven’t read. I get the sense their writings are too ornate for my taste, or too fantasy-oriented, or too opinionated. I am left with the impression their writings would fail to stir my sense of wonder.

Machen, for instance, seems a right twit. Deeply religious, he appears to have been even more obsessed with sex than D.H. Lawrence, and in nowhere near as positive a way. To him practically every aspect of sex was aberrant and a source of evil. His famous novella The Great God Pan was denounced by Victorian critics as “the product of a diseased, decadent mind… appalling, even abominable.” I gather Pan is revealed as the Devil, and not the ecstatic, liberating god of Greek Myth. Isadora Duncan would not have approved.

On the other hand, in his essay Supernatural Horror in Literature Lovecraft comments: “Of living creators of cosmic fear raised to its most artistic pitch, few if any can hope to equal the versatile Arthur Machen, author of some dozen tales long and short, in which the elements of hidden horror and brooding fright attain an almost incomparable substance and realistic acuteness.” So, maybe I shouldn’t dismiss Machen so lightly.

Of Algernon Blackwood, Lovecraft writes: “Of the quality of Mr. Blackwood’s genius there can be no dispute; for no one has even approached the skill, seriousness, and minute fidelity with which he records the overtones of strangeness in ordinary things and experiences… he is the one absolute and unquestioned master of weird atmosphere…”

Which is cool, but he also lambasts Blackwood with criticism: “Mr. Blackwood’s lesser work is marred by several defects such as ethical didacticism, occasional insipid whimsicality, the flatness of benignant supernaturalism, and a too free use of the trade jargon of modern ‘occultism.’ A fault of his more serious efforts is that diffuseness and long-windedness which results from an excessively elaborate attempt, under the handicap of a somewhat bald and journalistic style devoid of intrinsic magic, colour, and vitality, to visualize precise sensations and nuances of uncanny suggestion.”

Hmm, reading the above has just given me a massive inferiority complex. Compared to Lovecraft, I suck as a critic. Oh, well. I works with what I’ve got. Best I can do.

No need to get bogged down in details. The account of a young but brilliant Lovecraft meeting the literary “heroes” he has worshipped from afar is a hoot. I enjoyed reading the entire sequence. Heck, he would have enjoyed reading it. It’s what he always wanted.

Now we come to the fourth and final section of the book, the actual battle with the forces of evil. Knowledgeable readers can identify the principle villain just by glancing at the cover, but if you can’t, I say no more.

Most of the heroic characters are shown on the cover as well. In the centre you see Kat Branigan and H.P. Lovecraft standing side-by-side. And counter-clockwise from the top, the “ghost” of Edgar Allan Poe, an angrily aggressive William Hope Hodgson in a blue coat, a bespectacled Montague Rhodes James wearing black, a Quasimodo-like Arthur Machen in Green, an intensely-concentrating Algernon Blackwood in purple smoking jacket, and a gesticulating military-garbed Lord Dunsany. Above them note, from left to right, the presence of a Fungi from Yuggoth, a Cthulhu Spawn, and a Night-Gaunt. These are but some of the beings involved in the climactic battle which lasts several chapters.

The novel, though wonderfully evocative of Lovecraft’s thoughts and views on literature, is not at all structured like a typical Lovecraftian story. For one thing, it has a plot. Here is Lovecraft’s view as mentioned in an November 1930 letter to August Derleth: “I utterly despise plot as a cheap mechanical device.”

And, of course, the final battle is an extended action sequence. I can’t put my finger on the exact quote, but I recall that in one of his letters to Robert E. Howard, author of Conan, Lovecraft decried the formulaic and low-brow demands of magazines like Weird Tales. His best work, he complained, which relied on mood and atmosphere, was continually being rejected in favour of derivative, unimaginative, and repetitious stories culminating in “action sequences” with no more artistic or intellectual value than a boxing match. He found this disgusting, and evidence of the decline of Western civilization. Whereas only a sensitive, intelligent mind was capable of grasping his subtle nuances of cosmic terror, and such were few to be found on the editorial boards of pulp magazines. I’m afraid he probably would have found the ending of this book too commercial and somewhat tawdry.

I, on the other hand, loved it. Would make for a heck of a climax of a movie, one with a big budget because it would require extensive use of CGI. Given movies with large casts of heroes like The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Lord of the Rings, or even Kelly’s Heroes, I can see The Assaults of Chaos being made into a popular and successful film. At first it would depend on the delightful interaction between fascinating characters, but ultimately it would depend on visually satisfying eye-candy. I’d pay to see it.

Alas, as a writer, Lovecraft had no commercial smarts. He found the whole process of submitting to editors humiliating. Many of his stories he refused to submit, but circulated privately among friends. The bulk of his limited income came not from writing, not from ghostwriting (such as a story he rewrote for Houdini), but from freelance editing. He did quite a bit of that, and relished the anonymous nature of the task. He never had a clue how to market himself.

If it weren’t for August Derleth and Donald Wandrei, who founded Arkham house after his death to publish his works, Lovecraft would have been largely forgotten. Then came S.T. Joshi, whose depth of research has unearthed new information and many new letters to add and expand our intimate knowledge of Lovecraft’s life and works. Thanks to his efforts, and that of Hippocampus Press, there is a renaissance of interest in Lovecraft. Few authors in the history of literature have been so well served.

CONCLUSION:

Having annotated virtually everything Lovecraft ever wrote, and studied his writing and life with intense scrutiny, probably no other scholar on Earth can “channel” Lovecraft the way Joshi can. This is his personal homage to Lovecraft.

In his postscript Joshi remarks: “It should be obvious to most well-informed readers that many of the passages in this book—especially those recording the spoken utterances of H.P. Lovecraft and his cadre of weird writers… have been culled, with suitable emendations, from the actual writings (stories, essays, letters and other documents) of the writers in question.”

Just one of the reasons why, if you love Lovecraft, you’ll get a real kick out of this book.

And why, if you know nothing about Lovecraft or the history of weird fiction, this is the best possible introduction to those subjects.

I find it wonderfully entertaining. As a Lovecraft fan, it makes me very happy. I think it very cool. Has pride of place on my bookshelf. Every Lovecraft fan owes themselves the pleasure of reading this book.

Check it out at: < The Assaults of Chaos >

Recent Comments