C. Stuart Hardwick is an American science fiction author known for exploring themes of technological impact, space exploration, and human resilience.

C. Stuart Hardwick is an American science fiction author known for exploring themes of technological impact, space exploration, and human resilience.

His work has garnered several prestigious awards, including the Writers of the Future contest and the Jim Baen Memorial Short Story Award.

He’s been translated into a dozen languages and appears regularly in top anthologies and magazines.

His background in technology and engineering provides a foundation of scientific authenticity to narratives that resonate with both intellect and emotion, making him a distinctive voice in speculative fiction.

If you were to create a superhero that had a weakness for something totally unexpected, like pickles or bubble wrap, what would it be and why?

If I were to create a superhero who had a weakness for something totally unexpected, it would absolutely be something like bubble wrap, and it would shared by the arch enemy super-villain, Here’s why:

If I’m honest, as a writer I find most fights and especially most superhero fights pretty boring. They all boil down to “who did the writer give the upper hand to? Can we just find out and get on with the story already?” There are exceptions, of course, and a well-drawn superhero has weaknesses and emotional entanglements for exactly that reason. But even when done well, it’s still easy to fall into the trap of good vs evil with neither particularly well motivated, and that’s hard to make compelling. I think that’s one reason the Black Panther movies were so good–the villain wasn’t “just drawn that way,” but rather had a different and well justified opinion about what the right thing to do actually was. Which brings me back to bubble wrap. In a well-crafted story, super dude and super badie need a chance to chat, to realize they’re really on the same side, they just got at loggerheads along the way. Maybe in the midst of fight du jure one of them (could be either) steps on a scrap of bubble wrap and is paralyzed, pouncing on the stuff like catnip while flood waters or fire (or whatever) rage near. Meanwhile, their opposite is sucked in, first by the beguiling “pop” of little plastic bubbles, then by the realization that if they don’t intervene, both their adversary/countryman and cause will be lost, and the only way to stop that is to risk the siren call of packing sheets themselves and…. Tune in next week for, Pow! Bam! Zing! Now in Spectravision!

If you had to choose between being a mermaid or a dragon, which would you pick and why?

What, you’ve no room for merdragons in your fantasy world? Man, that’s so terrestrialist…or something. Personally, I’d go with mermaid, though I gather “merfolk” is the preferred term (after all, not everyone can get the coveted “maid” slot). I mean dragons are kick-ass and fire-breathing and all, but imagine trying to get into a nice sushi place when you weigh 16 long tons and smell of brimstone. Besides, in many literary treatments, merfolk can trade the tail for legs under at least some circumstances, so that opens up trips to IKEA at least, to say nothing of spec work as a dog walker. Have you ever seen a dragon walking people’s dogs? You haven’t, have you? And that’s telling, you know–man’s best friend and all that?

Now this is during peacetime, of course. In wartime, I don’t want to be anywhere near anything that might go “boom” under water. Dragons are airborne, fireproof, and tough as well, dragon hide, and in a fighting war, a good match for anything short of a nuke or a patriot missile (and I wouldn’t bet on the latter). Dragons would be the ultimate surveillance platform and anti-drone attack dog, and in the fog of war, no one’s going to complain too much when they go digging around the rubble for spilt vittles. But if I’m going into combat as a dragon, I’m totally having my scales waxed and polished. It’s not very realistic, of course–the last thing you want in a war zone is to glitter in the sun–but where there be dragons, reality has gone on hiatus, and you might as well go for maximum bad-asserdry.

If you could time travel to any point in history, which era would you choose, and why?

Serious answer: If you know my writing, you might suppose I’d go back to the Library of Alexandria at around the 3rd century BCE, a time of unparalleled intellectual ferment and a confluence of knowledge from various cultures and civilizations. Or to 15th century Florence at the height of the Renaissance, where the seeds of the modern world were being sown. But those, in fact, would be low on my list. I’d go first to Egypt’s Old Kingdom, 4th Dynasty, late in Khufu’s Reign. I’d collect information about the construction of the pyramids, about their purpose and surrounding beliefs and politics, and about the economics and logistics of their construction. We don’t need any of that, except it would be sobering to people today to see that people back then were just as clever and capable, even if not as well educated, no aliens or conspiracy theories required. Then if my ride could take me, I’d go visit the Inca and the Aztecs and the Toltecs, and see how they did their thing and maybe bring back their lost writing. And then the Mississipians, and the Anasazi. And I’d like to see the (probably several different groups) behind Stonehenge and the nazca lines.

You might think that odd, a guy who writes about the future wanting to study the past, but it isn’t. The best science fiction, at least since the New Wave, has been introspective. It’s not about the future as much as it’s about our humanity, as revealed by our grappling with consequences of what we invent. In school, we learn history as a boring list of battles and dates, but it wasn’t that at all in read life. History is economics and struggle, an endless network of discoveries, failures, triumphs, and mistakes, woven together in ways both surprising and instructive. Filling in the gaps would be immensely valuable, not because we’ve lost any great wisdom of the ancients, but before all the little twists and turns that led us here are where much of the true wisdom lay, only hidden from anyone who might have thought to record it.

And if I went back and managed to take only memories, leave only footprints, and not completely dork up the universe, I’ll wager I’d return with compelling evidence that people have always been people, flawed and clever apes, and we don’t need aliens to build wonders or vast conspiracies to do evil. And maybe that would help a few of the more civilized among us get back to being more civilized.

If you could choose any real-life celebrity to make a cameo appearance in one of your books, who would it be and why?

Well…Astronaut Gus Grissom and aviator Jerrie Cobb already appeared in my stories. Grissom appeared in “Catcher’s Mitt” to share the advice “do good work” and remind readers he was a real man whose legacy deserves better than his bumbling portrayal in Wolfe’s The Right Stuff. Cobb appeared in my novelette, “For All Mankind” to share a sandwich lunch on the wing of a biplane, spread a little moxy, and do what she did in life–encourage women to soar. I won an Analab for that story, and I believe writers have a responsibility to portray historic figures with accuracy and respect, even when narrative demands require liberties. I also brought back the much less famous Soviet Cosmonaut, Grigoriy Nelyubov in my second Open Source Space story “Dangerous Company” for exactly that reason, though I did fictionalize his family. In real life, Nelyubov got himself in some hot water that led to his being airbrushed out of official Soviet history. He screwed up, but he deserved better than to be forgotten, so I brought him back.

If you were to write a love story between a human and an alien, what challenges would they face?

This is actually a very important question, and perhaps a deeper one than it appears. The obvious challenges we can dispense with. The more interesting ones are: love based on what? Love is founded on admiration and ultimately on shared values. But human values are influenced by biology in ways almost invisible to us. Cute girls, sexy cars, and gorgeous sunsets are not objectively superior to anything else. We are evolved (some of us) to find them attractive and so we do. The same is true of morality and character. We see scripture as a moral authority while ignoring passages in which it’s anything but. The truth is, our values, food preferences, tastes, and motivations all reflect our biological evolution as apes on this particular planet, normalized by consensus and enforced by social constructs. And in spite of that, we fight over them, sometimes admiring, even loving, the very things in our own kind that others hate. What basis then, for love between beings from other worlds? And what form would that love take?

Aliens could be very alien indeed, even with a very similar biology. The Klingons are war-like but value honor, and we can admire the one trait without embracing the other. But aliens—even not terribly alien aliens—might well share some of our most prized virtues while at the same time embracing what we find objectionable, even evil. Slavery, fratricide, infanticide, cannibalism, and genocide are not even universally rejected by all humans, and barely scratch the surface of what might exist among a diversity of civilizations from other worlds. For that matter, any civilization advanced enough to meet us might strike us as unbearably arrogant, officious, ruthless, condescending, or dismissive—yet still possess much to be admired by our own standards.

So… love? The easy way out (for the author) is to remove the alienness, to make the alien basically a weirdo human in a catsuit—but that’s cheating. Or, as has too often been done, make the alien the exception (even traitor) to the alien norm of its kind, or like the Borg, make it less and less alien the more time we spend with it, until it’s just a weirdo human in a catsuit. And that’s definitely cheating. No, to do love justice, the alien must be truly alien, probably disturbingly, stomach-turningly so, and yet still have enough that is admirable, laudable, lovable, to make some form of human affection make sense. This has seldom—if ever—been done, and it’s a very interesting problem. It’s actually a problem I’m wrestling with in a story at the moment, so stay tuned.

If you had to choose between being a time traveler or a space explorer, which would you pick and why?

Space explorer. Logically, time travel just won’t work. Either you are traveling back through your own timeline, in which case almost any action you take will so disrupt the future as to probably tear your consciousness open, or you are in a parallel timeline, in which case all possibilities already exist and any action you take just moves you between preexisting realities, in which case nothing really changes, nothing is any more real than anything else. So nothing matters and you might as well stay home binging K-dramas and donuts. But to explore space is to learn, and if they are out there, to meet our cosmic neighbors. I would argue that peering over the horizon is the defining characteristic of the human species, so there’s nothing more human than steering “Second star to the right, and straight on til morning.”

If you had to choose one of your books to be turned into a cheesy made-for-TV movie, which one would it be and who would you want to play the lead roles?

For all Mankind. At this point, it would need a new title, I think, but it would be a good fit for the old TV Adventure Movie of the week. In 1970, an American tomboy and a Soviet engineer who’s secretly a German war orphan are covertly launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in a Saturn-V to save the world, and end up saving one another’s souls.

If aliens were to visit Earth, what do you think their first impression of humans would be?

Mmmm….tasty. Any aliens with the technology to come here in engineered vessels are not going to crash in the desert while being photographed through a foggy trailer park window. They’ll either show up, do what they came for, and leave without us ever knowing, or show up and take over without us ever mounting a meaningful defense. But probably at least as likely would be visitation by extraterrestrial microbes which could simply drift down through the atmosphere, take root, and make the triffids look like Bambi by comparison. Either way, I’m not going to lose any sleep over it. We’re a much bigger danger to ourselves.

What Pre-1960s SF television show or movie would you like to see get a big-budget remake, and why?

None. Most of the good ones have already been ruined for future generations–er, I mean “improved,” and most of the bad ones were only ever good for the camp. Make my stories instead, or those of my many award-winning friends. Lots and lots and lots of excellent new stories are being written, and Hollywood needs to pull it’s head out of the past before it’s eclipsed by the rest of the world.

If you were secretly an alienvisitor to the Earth, why are you here?

Coffee. Obviously. How is this even a question?

Define “Science Fiction” as Damon Knight did (“What we’re pointing to when we say ‘Science Fiction'”), but without using your finger.

As a writer, I much prefer “speculative fiction” or better yet, Usula K Leguin’s “Propositional Fiction” which clearly implies a world essentially like the one we inhabit except for certain speculative propositions such as “suppose there was this dude whose dreams came true.” That definition would include Harry Potter, even though science is almost explicitly excluded from its universe. Not that I don’t like fantasy, but even fantasy need to have rules but which characters must live or die, or else it hasn’t any stakes.

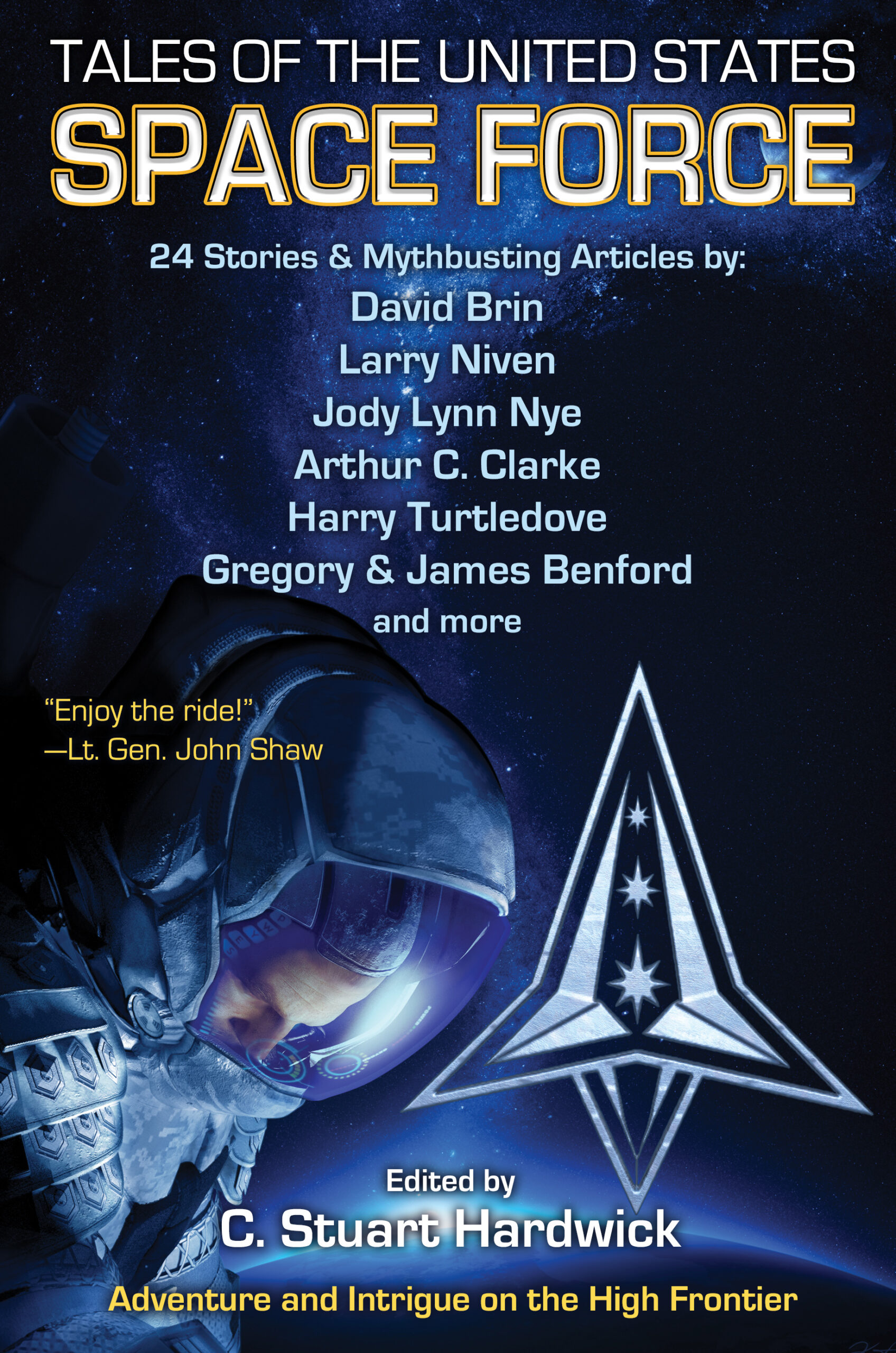

The fact of the matter is, genre terms are just labels that help readers find what they are interested in and editors announce what they’re buying. There are a LOT of such terms, “hard sci-fi,” “space opera,” “urban fantasy,” “cyberpunk,” etc., etc. None of these terms has an actual set definition, nor is any really possible. Such categories evolve with the times, and the important thing is not what we call them, but that we communicate meaningfully about them. It’s safe to say all the stories in Tales of the United States Space Force are science fiction, and that most are military sci-fi and hard sci-fi. But we also have aliens, romance, and a bit of police procedural, and a good deal of the science isn’t really fiction at all, leaving stories that are science fiction without being speculative fiction, which seems impossible these days but of course was par for the course back in the early days of Amazing Stories and Astounding Stories.

I would say that very broadly, today “speculative fiction” is often used to distinguish more cautionary, philosophical, or aspirational fiction of a “propositional” nature from space opera, cyberpunk, or urban fantasy that tends to be of lighter philosophical weight. Scient Fiction, then, is speculative fiction about science or technology, or propositional fiction that proposed some alteration in natural law. But there are so many counter examples and what the terms mean changes from reader to reader and evolves as new works come out and are shoehorned into the taxonomy. And maybe that’s a good thing. You can’t judge a book by its cover, but you can’t read and evaluate every tome in the universe–you have to start somewhere. Genre labels (and covers) are fine as long as they are only ever the starting point in the quest.

What projects are you working on, or appearances are in the future?

My new anthology, Tales of the United States Space Force is out now from Baen Books. It’s a collection of science fiction stories and articles illustrating the need for, and dispelling misconceptions about, America’s newest service branch, with stories by Arthur C. Clarke, Larry Niven, Harry Turtledove, Gregory Benford & James Benford, David Brin, Jody Lynn Nye and a host of award-winning rising stars. You might also like “Final Frontier” an anthology of uplifting space adventure celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Apollo moon landings, available on Audible.com.

***

To learn more and get a free story sampler, listeners can visit my website, www.cStuartHardwick.

To learn more and get a free story sampler, listeners can visit my website, www.cStuartHardwick.

Steve Davidson is the publisher of Amazing Stories.

Steve has been a passionate fan of science fiction since the mid-60s, before he even knew what it was called.