Sean McMullen worked for the Australian Bureau of Meteorology for over three decades, in areas ranging across satellite tracking, systems design, disaster contingency and Year 2000 conversion.

Sean McMullen worked for the Australian Bureau of Meteorology for over three decades, in areas ranging across satellite tracking, systems design, disaster contingency and Year 2000 conversion.

During those same decades he went home and wrote science fiction after hours – except when a system crashed and he was called back to the Bureau.

Today he writes science fiction full time and teaches karate part time at Melbourne University.

He has had Hugo and BSFA award nominations, won 17 other awards including three Analog Readers Awards and had his work translated into over a dozen languages.

How have you used the phrase “I’m a writer” to avoid an unpleasant situation? What was it?

I was never a full time writer, I worked for the Bureau of Meteorology with very large scientific computers by day and wrote fiction by night. Inevitably, at parties, I would get asked what I do for a living. If I said I work for the Bureau of Meteorology, the response would almost inevitably be a variation on “When are you going to do something about all this weather?” or “I reckon all this climate change is a pile of crap, what do you think?” I could then respond by saying something stunningly rude and instantly make an enemy (and remember what Oscar Wilde said: “Choose your enemies with exquisite care”) or I could try to have a sensible dialogue (impossible with anyone capable of asking either of those questions). Far better to say “I’m a writer” (which was half true) to which the response would always be “Yeah? I’ve got a great idea for a book,” and to which I would reply “Really? Tell me all about it.” I could then sip at my drink while the unpublishable book was described to me, and think of polite, plausible excuses to slip away. I did this many times. I still do.

Name the strangest/weirdest place you’ve ever written. What made it so odd?

I presume you mean the strangest/weirdest place I have ever written in, and that would be Darwin, the only tropical capital city in Australia. I had been sent there to configure a new computer, and arrived from a freezing Melbourne winter and stepped out of the plane into very hot tropical conditions. At night, after work, sleeping was difficult. My motel room did not have working aircon. I did not acclimatise quickly, and there was a very large lychee tree next to the motel, which was visited every night by several hundred loud and raucous fruit bats. I had not brought a laptop, so I could neither sleep nor work on my science fiction. Eventually one of the forecasters in the Regional Office took pity on me and set me up with a PC. What she actually said was “It’s not working, but if you can fix it, you’re welcome to write your science fiction here at night.”

I got it working, and for several nights I did indeed alternate between writing a story and sleeping on the floor. After the sun came up I just had a black coffee for breakfast and went back to configuring the new computer. After a week or so the motel fixed the aircon and the fruit bats had stripped the lychee tree bare and moved on, so I was able to actually sleep in a bed, in a quiet and cool room. The story was eventually published as While the Gate Is Open, and it won me my first Ditmar Award (which is Australia’s version of the Hugo, sort of).

If aliens were to visit Earth, what do you think their first impression of humans would be?

“How did this bunch of violent, power-hungry, sex-crazed monkeys manage to build a global civilization and even establish a toe-hold in space?”

What’s the silliest misconception you’ve had about something scientific, what was it and how did you learn you had misapprehended?

When I was about seven years old, I thought that the stars were only a bit further away than the planets. Science fiction shows on radio and television assumed that faster-than-light engines were no big deal to build, and some even featured spacecraft that used rockets to reach the stars – in theory possible if you have a couple of hundred thousand years to kill. Then I chanced upon a book in the local library with a title along the lines of “Relativity for Schoolboys” (back then schoolgirls were not meant to be interested in that sort of thing) and I was horrified to discover that the speed of light could not be exceeded and worse, how very, very, very far away the stars actually were. By the time I returned the book to the library I was feeling very silly indeed, but it did inspire me to always check the facts carefully before jumping to conclusions.

If you had to choose between fighting 100 duck-sized robots or one robot-sized duck, which would you pick and why?

I would approach the choice logically, and ask myself “What would Mr Spock do?” In Robert Silverberg’s The Man in the Maze, young Ned Rawlins gets trapped in an ancient robotic cage which then summons dozens of little carnivores that slip through the bars. They are not hard to kill, but there are too many of them, and Ned only survives because outside help arrives. A very large duck, on the other hand, can be reasoned with. It is unlikely to attack because I am not a water weed, and if I say something like “Nice duck” and toss it a few bread crusts from my rations, it will probably leave me alone. On the other hand, all the little duck-sized robots will probably be programmed like Daleks, so they will approach me quacking “Exterminate! Exterminate!” and will not be bought off with a few bread crusts. So logically, I choose the big duck.

If you could travel to any alternate universe where a different version of yourself exists, what do you think your other self would be like?

I think my alternative universe’s other self would depend very much on when the particular universe split off. I shall give four examples.

If the split was when I was fourteen, that was when I got honours in high school English for two science fiction stories I submitted for the mid-year assessment. Bear in mind that Terry Pratchett had his first fantasy story published at about that age, so we were both showing early promise. If I had then submitted those stories to the big British SF magazines, I might have been discovered as an author a couple of decades early, instead of spending that time in folk-rock bands and getting multiple university degrees. My alternate universe self might well be a rich author who would say to me “If only you had kept writing at fourteen.”

When I was 24 there was another universe-diverging event in my life. I was in a bar, chatting up quite a charming young woman from the university choir, when a friend of mine came over and said “There’s a guy named Miller over there who is looking for actors who can ride motorbikes. You ‘re an actor and you can ride, so why not speak to him?” I decided that dating the woman from the choir would be far more fun than acting in some amateur movie, so I said “No thanks.” That movie turned out to be Mad Max (Road Warrior). This time my alternative universe self would be an actor who had made his name in Mad Max, then moved to Hollywood and later became really famous. This time my alternative self would say, “Hey, how did your date with Pat go?” and I would think about what a high price I paid for that date.

Also at age 24, a member of a new folk band called the Bushwhackers asked me if I might like to join as relief lead singer. The Bushwhackers later became Australia’s top folk band. At the time I replied that I wanted to finish my degree, so thanks but no thanks. This time my alternate self would say nothing because he would probably be dead from lung cancer – a legacy of spending decades singing and playing in pubs choked with cigarette smoke. And I did manage to finish that degree.

Lastly, at age 32 I had job offers in computing from Siding Springs Observatory, Shell, BHP and the Bureau of Meteorology. The first three jobs involved moving interstate, but I had just bought my first house and the Bureau’s head office was local. If I had chosen either Shell or BHP, I might well have worked my way up the corporate ladder instead of doing more satisfying scientific things to pay the mortgage – as well as writing science fiction after hours. My alternate self might be very rich, but he might say “Gee, I keep having all these great ideas for science fiction stories, I wish I had chosen the Bureau all those years ago.”

Were any of those alternative selves better than my real self? (apart from the one where I die)? Define better.

If you could swap lives with any character from one of your books for a day, who would it be and what would you do?

At first I thought it would be John Glasken from Souls in the Great Machine, then I thought about it and decided that I did not want to be him, even for a single day. On the other hand, it is worth tracing through why I thought of Glasken first, then rejected him.

John Glasken was a drunken, brawling, womanising, gambling university student, and as long as the chosen day was before his rather psychopathic and deadly girlfriend, Lemorel, discovered that he has been cheating on her, he had been leading a rather enjoyable, if dissolute, life in the taverns of Rochester. When I was at university I did indeed hang out in pubs, but they were generally pubs that featured folk music clubs. I only drank moderately. Because drink cost money, I was poor, and I had to work part time to feed myself and pay the rent. When the pubs closed I would move on to the university computer centre (I had a security pass, and PCs had not been invented back then) and get on with my coursework. This made it difficult to chat up girls, because “Hey, would you like to come back to the computer centre with me? I know a nice secluded spot behind the VAX 11-780” is not a winner as pickup lines go. Brawling? Not for me. As soon as a fight started we musicians all hunched over our precious instruments and ran for the nearest door. Gambling? No way! I had studied probability theory and knew the odds were never fair.

Bearing all that in mind, John Glasken came from a rich family and had a very generous allowance, so he could do all the things that I could not. Worse, I came across as a well behaved and responsible sort of guy, while Glasken was a bad boy. In my experience ,many girls thought rich bad boys were way more fun than poor, hard working sods like me. Yes, at first I believed I would like to experience life as John Glasken did, just for one day … but now we come to the crucial question: How did I learn so much about the bad boy lifestyle without being one? Most girls who dated me tended to have a bad boy in their past, so they were sympathetic toward any guy who was at least halfway civilized and well behaved. When we dated, they always had a great many nasty things to say about how badly they had been treated by dissolute young guys from rich families and I actually felt quite sorry for them. So, on second thoughts, I don’t want to be Glasken, even for only one day.

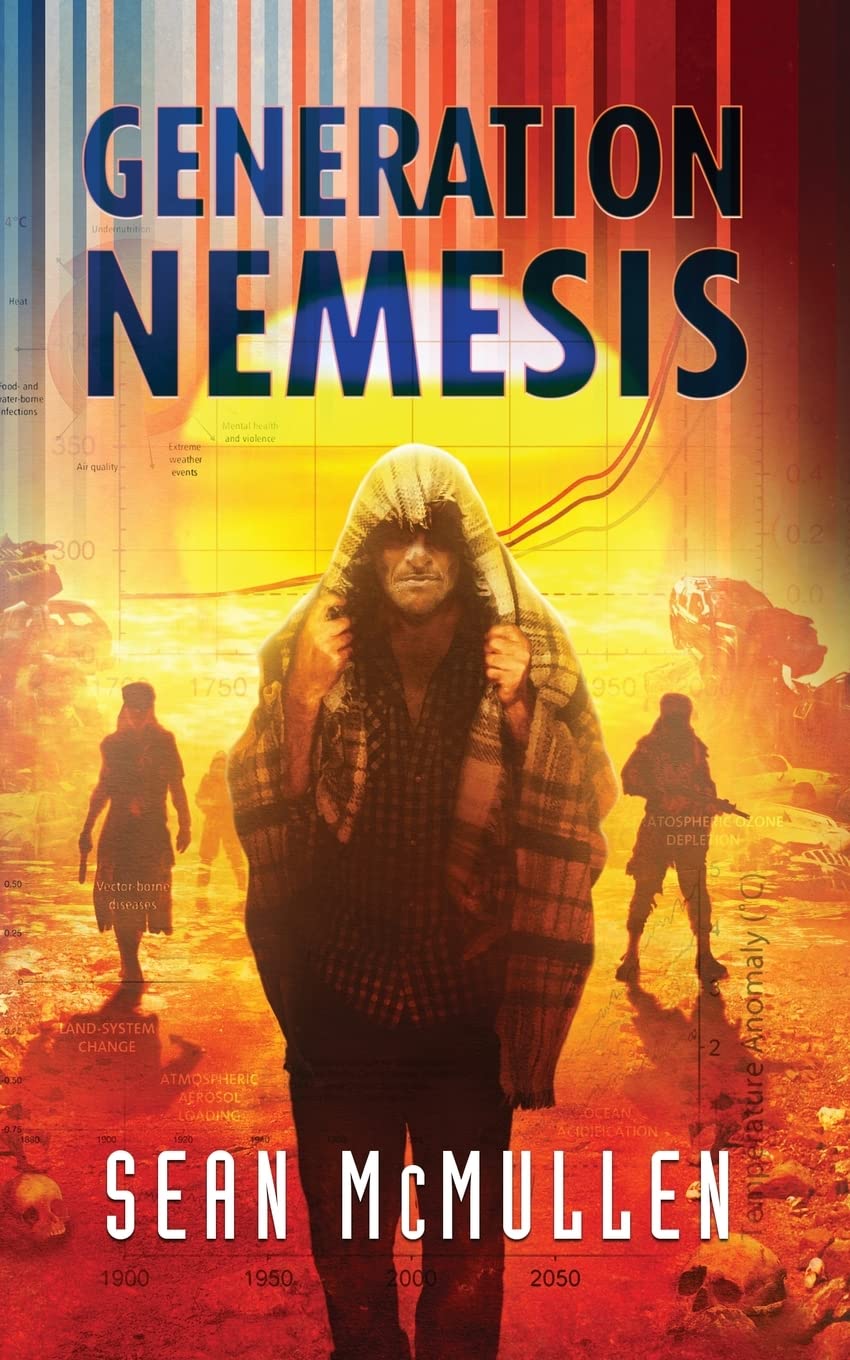

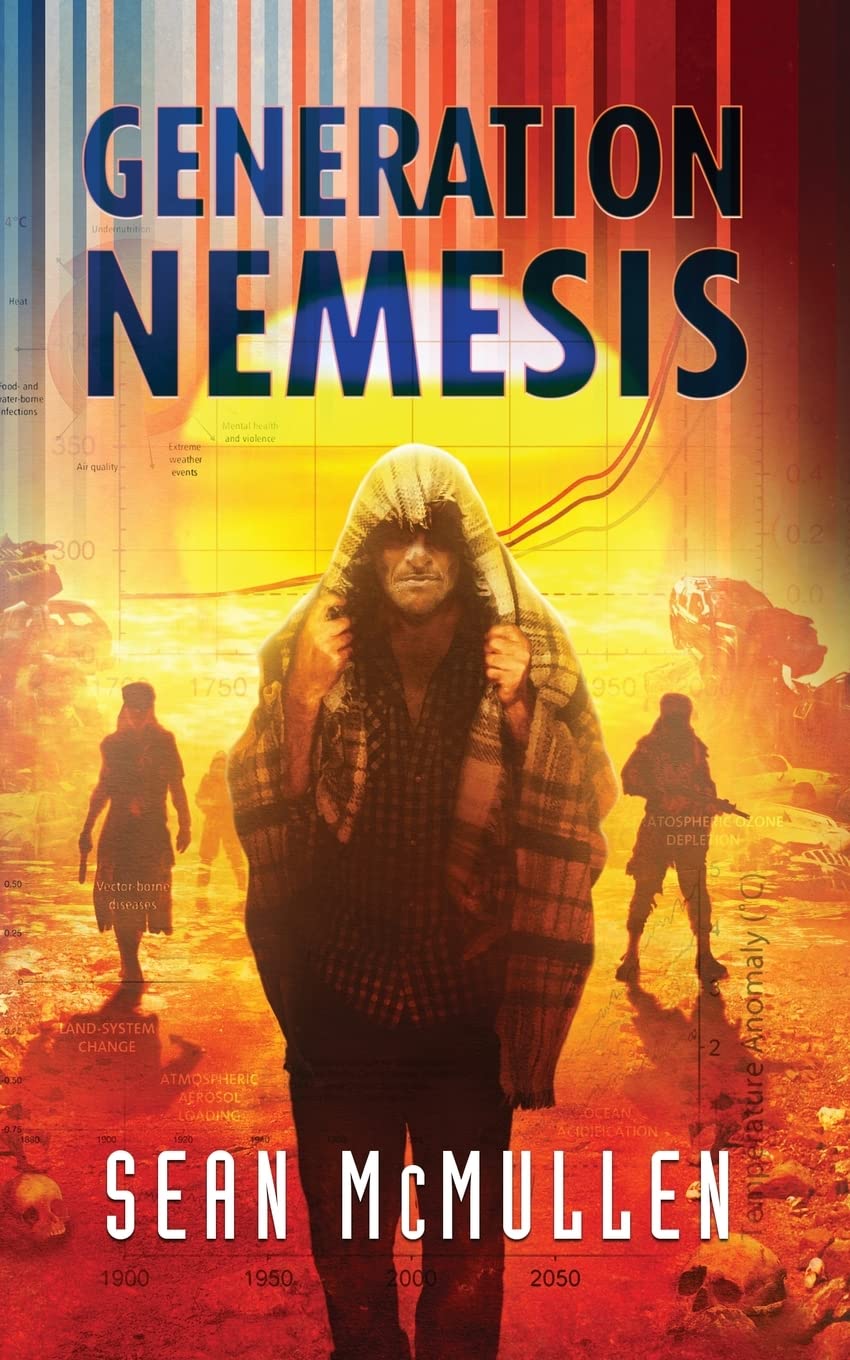

Instead, better make that Jason Hall, the climatologist from my latest novel, Generatiion Nemesis. His agenda is to save the world from climate change, but he still gets to go to some great parties.

***

Speaking of Generation Nemesis and Jason Hall, buy the book and check out the guy I would happily swap lives with:

Speaking of Generation Nemesis and Jason Hall, buy the book and check out the guy I would happily swap lives with:

Praise for Generation Nemesis

“In a near future Australia, where the children of the 21st century are putting the children of the 20th on trial for the murder of the world, one octogenarian climatologist dares to expose the hypocrisy of their justice. But can he beat the system? And if he does, what will be his prize? Pulpy, provocative and pedagogical, this ain’t your grandad’s cli-fi; it’s a novel-length thought-experiment in generational climate morality, delivered with the dead-pan Antipodean excess of Peter Jackson’s early movies. If you’re not appalled, you’re reading it wrong.” Paul Graham Raven

Sean is best known for his Greatwinter science fiction series (Tor), and his latest adult novel is a dark comedy about climate change, Generation Nemesis (Wizards Tower Press, 2022). He has a PhD from Melbourne University.

Website: https://www.seanmcmullen.net.au

Facebook: Sean McMullen

Instagram: sean_c_mcmullen

Hardcopy edition

Amazon US

https://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/1913892441/emeraldcity0d0

Amazon UK

http://www.amazon.co.uk/exec/obidos/ASIN/1913892441/emeraldcity0a

Amazon AU

https://www.amazon.com.au/exec/obidos/ASIN/1913892441

Amazon DE (Germany)

https://www.amazon.de/exec/obidos/ASIN/1913892441

Barnes & Noble (US)

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/generation-nemesis-sean-mcmullen/1142553274?ean=9781913892449

ELECTRONIC edition

Amazon US

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/B0BK59C4W4/emeraldcity0d0

Amazon UK

http://www.amazon.co.uk/exec/obidos/ASIN/B0BK59C4W4/emeraldcity0a

Amazon AU

https://www.amazon.com.au/exec/obidos/ASIN/B0BK59C4W4

Barnes & Noble (nook)

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/generation-nemesis-sean-mcmullen/1142553274?ean=2940185833551

Kobo

https://www.kobo.com/au/en/ebook/generation-nemesis