Jupiter looms in he sky. A small band of men gaze up the majestic sight from beneath a large fern-like tree on what can only be one of the planet’s moons. Nearby stands their means of arrival: a cylindrical craft of roughly thirty feet tall, with a neat row of circular portholes down the side. It was November 1928, and Amazing Stories had landed once more.

Jupiter looms in he sky. A small band of men gaze up the majestic sight from beneath a large fern-like tree on what can only be one of the planet’s moons. Nearby stands their means of arrival: a cylindrical craft of roughly thirty feet tall, with a neat row of circular portholes down the side. It was November 1928, and Amazing Stories had landed once more.

Hugo Gernsback’s editorial for the month is entitled “Amazing Life”, and expresses awe at the wide variety of habitats to which terrestrial life is adapted:

Neither great heat nor extreme cold seems to discourage the generation of life. Of course, there is a limit to the temperature variations, because no living being has thus far been known to exist in temperatures such as boiling water. Yet, even here, there are bacteria which can live in boiling water for a few minutes—anthrax, for instance.

Taking the topic in a more scientifictional direction, Gernsback concludes by pondering the possibility of life existing in the void of space:

Arrhenius, indeed, was the first savant who imagined that any living organism could exist in the interstellar cold, which is—459.4 degrees below zero Fahrenheit, and at the same time live in an almost perfect vacuum, a thing that has never been conceded before.

Yet, there is no good reason to believe that living beings, even of a comparatively higher order, should not find it possible to live quite comfortably in a vacuum and at absolute zero. If nature should find it necessary to evolve a creature to live under such conditions, it seems quite likely that it could be, and perhaps has been, accomplished.

Two of the stories in this issue do indeed depict complex life in unusual places, albeit not in the vacuum of space: instead, it is the interior of Earth and a moon of Jupiter that turn out to be the habitats of strange humanoids. The remaining stories, meanwhile, are focused on terrestrial adaptation, exploring ways to improve – or replicate – the human body…

The World at Bay by Bruce and George C. Wallis (Part 1 of 2)

In the near-future of 1936, reporter Max Harding is tasked with writing up a story on the discovery of airships “manned by queer-looking beings from the Lord knows where” which, according to eyewitnesses, have been mounting attacks on sea vessels. Speculation flourishes as to the identity of the pilots: are they Japanese, or “civilized savages from the depths of the Amazon forests”, or even invaders from another planet? Whoever they are, they are operating from a camp in Rio de Janeiro — but anyone who gets too close is either killed or captured, and even approaching aircraft are brought down through mysterious means. Max and his fellow reporters Dick and Rita arrive in time to see Rio de Janeiro transformed into a warzone, the population devastated by a poisonous gas:

In the near-future of 1936, reporter Max Harding is tasked with writing up a story on the discovery of airships “manned by queer-looking beings from the Lord knows where” which, according to eyewitnesses, have been mounting attacks on sea vessels. Speculation flourishes as to the identity of the pilots: are they Japanese, or “civilized savages from the depths of the Amazon forests”, or even invaders from another planet? Whoever they are, they are operating from a camp in Rio de Janeiro — but anyone who gets too close is either killed or captured, and even approaching aircraft are brought down through mysterious means. Max and his fellow reporters Dick and Rita arrive in time to see Rio de Janeiro transformed into a warzone, the population devastated by a poisonous gas:

Death—for death it was, without the shadow of a doubt—had been sudden. The prevalent expression on all faces was that of frightened surprise. And every one of these quiet thousands was shrunken and shriveled to a skin-clothed skeleton. It was as though the gas had withered them internally.

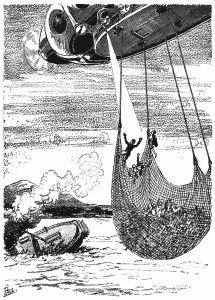

They spend days in battle-scarred Rio, during which the city is hit by another gas attack from the mystery airships; by chance, the visitors find themselves among the scant survivors. Eventually, the reporters are captured in metal nets deployed by the strange aircraft. On board, they are menaced with a “deadly, paralyzing ray of light” before being taken to a forest where they are inspected like animals, prefiguring alien abduction narratives of later decades: “Helpless, inert, capable only of seeing, understanding, fearing, we were passed in review like so many cattle, so much livestock. They prodded us, turned us over, emptied our pockets, annexed our revolvers, knives and watches, and finally sorted us into two lots.”

After this, they are taken to the creatures’ underground lair, and get a closer look at the “Troglodytes”:

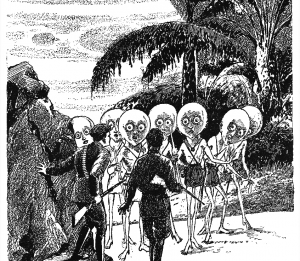

They were short and squat, ungainly of limb, long-armed like apes, and ghastly pale of skin, as though wilted and bleached by the hot, humid air. They wore no head-coverings on their short, fuzzy mops of brownish hair. One rough, coarse, ill-fitting robe of dark material, reaching to the knees, and a sort of sandals on the feet, completed their wardrobe. Indeed, their climate, warm and equable, made anything more needless.

As to the sexes, they appeared to dress exactly alike, and one could only distinguish them by the softer, more curving contour of the bare limbs, and that “something different” in the eyes that baffles all analysis of words.

They looked what they were—creatures of darkness, born in everlasting gloom, and yet creatures somehow akin to humanity.

It transpires that the Troglodytes’ human captives are forced to mine for radium, used to power the creatures’ aircraft. A captive named John Rixon informs the newcomers of the social structure that they now inhabit:

“They want us—they need us—to work. That’s why we call ourselves the Slaves. There are about seven or eight hundred of us here in camp—at present. There have been more, a lot more . . . Many nationalities; quite half of us are brown or black. A party of us decided to run this show on some sort of basis of law and order. Oh, we have quite satisfied ourselves that there is no way out. We have a sort of government—I’m President, as it happens—police, commissariat, news service, medical service, sanitation, and so forth. The idea is to keep people occupied, not to let them think too much.”

Max Harding is thrown into despair, partly by the prospect of slaving away in a radium mine (“Intrepid scientists, using only minute quantities of radium, have died painful deaths in consequence… Live! It would be life worse than death”) and partly by envy of the affection that Rita gives John Rixon. But the heroes manage to escape a life in the mines: by making an effort to learn the language of the Troglodytes, they are instead kept around as intellectual curiosities.

During this time, Max uses his radio know-how to develop an understanding of the Trogs’ technology (“I saw enough to realize that the paralysis ray and ray for dissolving the poison gas are similar to short-length wireless waves. The apparatus, though more complicated, is similar in essentials to a wireless transmitter”). The heroes also witness the forbidden romance between two Trogs, named Ulf and Ulla, which ends with the unfortunate pair being executed. Finally, the four decide to stow away upon a Troglodyte aircraft – but only Max and Rita manage to escape.

With the aid of a parachute hastily sewn together from their clothes, the pair reach the land. Making their way through a ruined city, which turns out to be Sydney, they meet a local named Hopkins. He expounds an every-man-for-himself philosophy and shows little regard for them — until he finds that they have seen the Troglodytes close up. Together, the characters discuss ways in which they might get the upper hand over the attackers:

“The Trogs are wonderfully clever, especially down at home in their cave-world,” explained Rita. “But up here they are somewhat blundering and very ignorant. They can’t have much idea of our world — of its extent, its distribution of land and water. The immense areas of ocean must astonish them greatly. Only the speed and staying power of their radium engines have enabled them to get about the world at all. They have no maps, they know nothing of the compass (at least, so I think) ; they just have to feel their way about in a haphazard fashion. It must have occurred to these particular Trogs that we, setting out so determinedly, had some definite destination in view. They probably think that we shall lead them to some land as yet unknown to them.”

The first half of the story ends with a small-scale victory as a naval ship blasts a Trog aircraft out of the sky. But there is still much work to be done, as Naval Commander Jackson makes clear when he delivers a very of-its-time portrait of social unrest:

“Baltimore and Chicago have been smothered under poison gas, and many prisoners scooped up.

What they took prisoners for, of course, nobody knows, but these sudden and apparently haphazard attacks have completely demoralized large sections of the population. The blacks have almost got out of hand. They are either running amuck, killing and burning, or they have ceased to work and give themselves up to orgies of religious fanaticism.

The terror hangs over America like a thundercloud, trade is paralyzed, credit is falling. Till recently, there was a frantic emigration to Europe. Everybody feels insecure, anxious to hide or to run ; nobody trusts the banks, nobody will speculate. People are privately hoarding money, valuables and everything useful, preparing for the chaos they expect when the big cities and Governmental centers are destroyed.”

As a story about technologically-advanced invaders laying waste to human society, The World at Bay has obvious similarities to H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. However, cousins Bruce and George Wallis depict the invaders not as alien molluscs but as troll-like creatures who live underground – more like Wells’ Morlocks than his Martians (subterranean races were a reasonably popular theme around this time: see also Edgar Rice Burrough’s Pellucidar series and A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool).

Another difference is that The World at Bay clearly shows how World War I had impacted invasion narratives of this sort. The story opens with Max announcing that the Trogs’ attacks formed “a terror, beside which the terrors of the Great War were only as the rumblings of stage thunder” while the later sequences of poison gas attacks on Rio de Janeiro is a chilling reminder of how warfare had changed since Wells wrote his novel. An example of more positive social change can perhaps be found in the character of Rita, a remarkably capable heroine – it is she who has the idea of turning her dress into a parachute, after all. Max admits to having his “old-fashioned ideas on woman’s true sphere of life” challenged by her personality.

The story’s fantastical vision of the Troglodyte society contrasts strangely with its gritty depictions of hardship and devastation. One harrowing scene has the heroes escape onto a boat, which soon becomes so overloaded that the skipper is forced to turn away any further refugees; when the gangway fills with screaming women and knife-wielding men, he wards them away by brandishing his revolver. Despite this measure, the boat remains wedged in a mudbank, and those on board collapse into violent mayhem while the invaders arrive to do their work.

“The Moon Men” by Frank Brueckel Jr.

Inventor Henry Lloyd believes that gravity is “some sort of wave-motion emanating from every concentration of matter… produced by the motion of electrons revolving about the nucleus of every atom of matter.” Working with this theory, he comes up with an invention that can nullify gravity by reflecting the wave-motion back on its source. He partners with his friend Bachus to build an unmanned rocket, propelled by this new device, and send it to the Moon; following this success they begin planning a manned expedition, but Bachus dies before he can take part. And so, Lloyd instead teams up with his associate’s son, Clyde Bachus.

Inventor Henry Lloyd believes that gravity is “some sort of wave-motion emanating from every concentration of matter… produced by the motion of electrons revolving about the nucleus of every atom of matter.” Working with this theory, he comes up with an invention that can nullify gravity by reflecting the wave-motion back on its source. He partners with his friend Bachus to build an unmanned rocket, propelled by this new device, and send it to the Moon; following this success they begin planning a manned expedition, but Bachus dies before he can take part. And so, Lloyd instead teams up with his associate’s son, Clyde Bachus.

They put together a flyer called the Space-Waif, which Lloyd equips with provisions, weapons and “book-shelves holding every story of interplanetary traveling that he could get, besides a number of scientific romances”. Accompanied by a Russian named Rosonoff, a German called Lenhart and American mechanic Benton, they fly off at a speed of 1000 miles a second towards the Moon.

During the flight, Lenhardt fears that the crew “might suffer from the effects of the Cosmic Ray, discovered a while ago by Dr. Millikan, and which is supposed to emanate from the stars” but Lloyd explains that the flyer’s windows are made from a protective crystal, which will shut out the effects of the rays. Something does go wrong, however: the vessel malfunctions and goes off course. Rosonoff declares that the engine has been saboutaged, possibly by one of the crewmen.

The Space-Waif misses the Moon and ends up approaching Jupiter. The crew’s oxygen nearly runs out, but they are saved when the vessel lands on Ganymede, which turns out to have a breathable atmosphere. Their surroundings are picturesque, with a blue sky and trees resembling gigantic ferns (“such flora as must have existed on our own planet during the carboniferous period”). But then they notice a huge scaled beast — “Some sort of carnivorous dinosaur not native to our own planet”, as Lenhardt describes it — and retreat back to the ship.

While the others stay outside, Bachus and Rosonoff head out alone, leading them to encounter a band of humanoid beings:

Before us were seven new monstrosities-—seven feet tall from their small, aristocratic, high-arched feet to the tops of their great globular heads—-and in his dainty right hand each one clutched a glass rod about two feet long. For a long minute we faced each other-—these creatures of Ganymede and we Earth-men. During this period I was enabled to see the creatures more carefully. Their heads were almost perfectly round, about two feet in diameter, and perfectly hairless. Their features were human—two large, round eyes, almost white, except for the pupils, but the lids were very thin and delicate, and there were no eyebrows or hairs on the lashes. The noses were long and thin. In each case the mouth was small, the lips full and very red. The chins were long and pointed. Their bodies were rather narrow-shouldered and tapered down to thin waists, narrow hips and long, slender legs. Altogether they made me think of so many upright wedges. The color of their skins was an extremely light tan.

The glass rods are vacuum tubes, which the aliens use to knock the space-travellers unconscious. Bachus awakes to find himself and Rosonoff taken captive; alongside them are what appear to be a number of other Earth-men who are kept as slaves. It turns out that these latter people are not captured Earthlings, but rather an indigenous specimen of the genus Homo.

Learning to communicate with the slaves, the space travellers find out more about Ganymede. The bulpous-headed people are called the Ja-vas, and see themselves as spiritually superior: they were mortally offended that the newcomers did not pay due deference to their persons. The captives are taken to the opulent capital city of Putar where they are granted an audience with an indignant monarch, and subsequently sent to a mine of glowing red rock. Here, Bachus becomes infatuated with Navara, a “Moon Girl” who cooks food for the slaves:

She was not merely pretty, or even beautiful—she was divine! I had seen many beautiful women on Earth, and had admired them in a way. But this woman made me whistle softly and mutter, “Boy, what a peach!” under my breath.

With the aid of vacuum-tube weapons stolen by Rosonoff, the slaves manage to revolt; Navar is reunited with her enslaved tribe-mate Thoom, provoking Bachus’ romantic jealousy. Bachus accompanies the freed slaves back to their tribe — Navar and Thoom turning out to be siblings rather than lovers — and the Ja-vas’ building is destroyed by a bomb left by Rosonoff.

Despite this victory, the story has a downbeat ending. Navara is killed by a dinosaur, and Bachus arrives back at the Space-Waif only to find the crewmembers gone. He reads a note left by Lloyd explaining that there had indeed been a saboteur on board — Benson — who has since been killed; Bachus then receives a message from Lenhardt, stating that he and Lloyd had gone looking for their comrades only to be attacked by “a tribe of savages” leaving their survival doubtful. Bachus is left to wait for Rosonoff, who never appears.

Apparently the sole survivor of the expedition, all Bachus can do is take the Space-Waif back to Earth, where he laments that “life has held no charms for me—-my intimate friends are gone, and Navara’s sweet face haunts my dreams ever since that desolate Ganymedean day.”

“The Moon Men” is a lopsided story, beginning with a detailed, nuts-and-bolts account of space travel before seguing into a derivative adventure on an alien world. The plot has little that had not been already seen in Amazing (indeed, there are obvious similarities to this very issue’s The World at Bay, which likewise has humans being enslaved and sent to mines by strange humanoids – and even has a similar subplot dealing with romantic jealousy).

“The Ananias Gland” by W. Alexander

Renowned surgeon Dr. Arthur Wentworth receives a visit from George F. Ballinger, who reports a unusual complaint that is threatening both his career and his marriage: he is a compulsive liar. “I lie when the truth would serve my purpose much better”, he says. “I cannot describe the most common incident, I cannot answer the simplest question, without being overcome with this uncontrollable impulse to lie.” Dr. Wentworth offers a diagnosis:

Renowned surgeon Dr. Arthur Wentworth receives a visit from George F. Ballinger, who reports a unusual complaint that is threatening both his career and his marriage: he is a compulsive liar. “I lie when the truth would serve my purpose much better”, he says. “I cannot describe the most common incident, I cannot answer the simplest question, without being overcome with this uncontrollable impulse to lie.” Dr. Wentworth offers a diagnosis:

It has been learned that the closeness with which a person adheres to truth, depends entirely on the condition and development of a ductless gland located just below the medulla oblongata, in the back of the head. This gland they have quite properly named the Ananias Gland. My X-ray shows that you have an abnormal development of this gland, the only remedy being an operation to reduce it to normal size.

The operation is a success, but comes with a drawback. Robbed of the ability to lie, Ballinger proceeds to criticise his wife’s appearance, insult the nephew of a dinner host, and sabotage an investment deal by selling his employers short. His life in ruins, Ballinger’s only choice is to return to Dr. Wentworth and have his ability to lie restored – this time reaching a happy medium.

W. Alexander had previously provided the stories “New Stomachs for Old” and “The Fighting Heart”, and the three stories share a formula. “The Ananias Gland” modifies the plot a little – in that it does not involve the patient inheriting the personality of the organ-donor – but it nonetheless uses the same basic gag of an operation that creates a disastrous character flaw.

“The Eye of the Vulture” by Walter Kateley

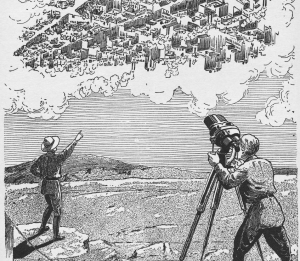

A survey party in a desert see a remarkable mirage: the inverted likeness of a city that they had passed through two weeks beforehand, the rooftops descending from the sky. Megg, one of the team members, expresses disbelief that a mirage of a city could be seen from so far away; but the unnamed protagonist who narrates the story explains that such phenomena has been recorded before. Their attention then turns to some nearby vultures, and Megg ponders how the creatures are able to see carrion from such considerable distances. He kills and dissects a pair of the birds to examine their eyes close-up.

A survey party in a desert see a remarkable mirage: the inverted likeness of a city that they had passed through two weeks beforehand, the rooftops descending from the sky. Megg, one of the team members, expresses disbelief that a mirage of a city could be seen from so far away; but the unnamed protagonist who narrates the story explains that such phenomena has been recorded before. Their attention then turns to some nearby vultures, and Megg ponders how the creatures are able to see carrion from such considerable distances. He kills and dissects a pair of the birds to examine their eyes close-up.

Years later, Megg has found work at a laboratory specialising in optical equipment. He invites the narrator over to see the results of his research into how vultures’ eyes operate:

“Naturalists have long suspected that there are short sound waves beyond the range of our ears, which insects can both hear and produce; though there is no definite proof that this is the case. Just what Nature uses all the rest of the infinite number of wavelengths for, we do not know. Neither do we know why she has been so stingy in letting us use them.

“However, we do know that waves of different lengths do exist, because we have been able to capture them with, for instance, the X-ray machine and the radio broadcasting machine.

“Well, it finally occurred to me that if Nature had been a little more liberal with the insects, in regard to sound waves, than she had been with us, she might have been a little more liberal with the vultures in regard to light waves.

“I reasoned that the vulture’s eyes might have been fashioned to sense one or two more wavelengths than we are permitted, thus giving them one or two more colors.”

Working on this theory, Megg researched infrared photography:

“Early in this investigation, I was impressed with the peculiar reactions of various salts of iron when brought in contact with solar light. One experiment, recorded by Lord Rayleigh, tends to show that when a plate treated with ferro-cyanide of potassium and ferric chloride is exposed to infra-red rays, color effects are produced.”

Finally, he came up with his new optical device:

“After much unsuccessful effort, I hit upon a plan of arranging a system of reflectors on a roughly rectangular form, endeavoring by trial to space them at such a distance from one another that they would create a wave interference.

“After much careful manipulation, I was able to arrive at a spacing that appeared to make a light red ray seem a little darker, or a violet appear a little nearer the indigo shade. That is, I was able to step each color up a very little toward the red end of the spectrum. I hoped, in this way, to be able to step some of the ultra-violet rays up among the violet ones, thus rendering any substance giving off ultra-violet rays visible.”

While testing this apparatus, he witnessed what appeared to be a form of violet smoke that was invisible to the naked eye; going to the source, he found that it was emanating from the body of a dead dog. The narrator tries out a newer, more compact version of the device, and is likewise able to see odours — or, more accurately, gases that carry odours. This, the two conclude, must be what a vulture sees.

Later, the pair chance to see another mirage of an upside-down city, as they had done years beforehand (“I had a feeling that this was one of those rare occasions when Nature deigns to notice its insignificant human souls, and in a spirit of condescension draws aside the curtains and gives us a long to be remembered glimpse of her treasures”, says the narrator, waxing lyrical). The sight turns out to be even more beautiful when viewed through Megg’s invention:

There was the city, just where it had appeared a moment before; but rising from a thousand places was a beautiful violet exhalation. In some places it rolled in billowing volumes; in others, it rose in thin columns; as smoke rises from a small chimney on a still evening.

Again it was only a thin vapor, which did not conceal, but mantled all with its veil of soft color. Gathering from all its various sources, it united in a vast and transcendentally beautiful cloud, which drifted away over the lake, illuminated and glorified by the light of the rising sun. The golden rays of our great luminary, mingling with the deep violet of the exhalation, resulted in a multitude of the most wonderful hues and colors.

“Think what a joy my ‘Smelloscope’ would have been to Nero!” says Megg, once the mirage has faded. “He could have experienced all the thrills of a burning city every day, while he retained them intact.”

Filled with technical details (“The longest waves that affect our eyes are the dark red, .0007621 millimeters; and the shortest are the violet, .0003968 mm. The intermediate ones produce the other colors”) this story marks a venture into hard SF of a kind almost totally alien to the later Campbellian tradition. Although the plot is minimal, the story nonetheless manages to be effective, its framing device of the mirage city being tenuous but nonetheless inventive and evocative.

“The Living Test Tube” by Joe Simmons

Leonard Giffin is sentenced to death for murder, despite pleading his innocence. Ted Moore, a district attorney, believes that Giffin was wrongly convicted — but Governor Stafford, who is rumoured to be corrupt, will hear none of it. Moore obtains the help of amateur criminologist Dr. Hausen in establishing Giffin’s innocence; on the night of the scheduled execution, both Moore and the story’s narrator — a reporter named Bob — are called over to Hausen’s laboratory.

Leonard Giffin is sentenced to death for murder, despite pleading his innocence. Ted Moore, a district attorney, believes that Giffin was wrongly convicted — but Governor Stafford, who is rumoured to be corrupt, will hear none of it. Moore obtains the help of amateur criminologist Dr. Hausen in establishing Giffin’s innocence; on the night of the scheduled execution, both Moore and the story’s narrator — a reporter named Bob — are called over to Hausen’s laboratory.

“Apparently there is a sinister influence at work in the Governor’s mind, which will prevent his issuing such an order”, proclaims Hausen when the prospect of the Governor calling off the execution is raised. “However, something has happened to me this evening, that, if put into a story, would be called impossible. Chance and a scientific mind to assist the goddess of chance, have cleared the matter for us.”

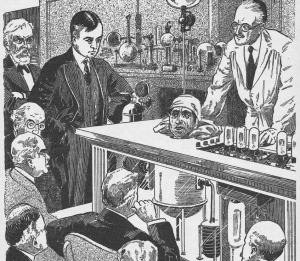

The doctor reveals that he has been experimenting on the body of Mark Farrel, a would-be robber who had died while fleeing the scene. He invites the Governor, along with a number of fellow scientists, over to the fruit of his research.

One hour before Giffin is due to be killed, Dr. Hausen gives a short speech on the history of attempts to preserve living tissue. He reveals that he has created a “living test tube” — a severed human head rigged up to a set of artificial organs. The head turns out to be that of Mark Farrel; when resurrected by the doctor using hypnosis, Farrel reveals that he has been working alongside the corrupt Governor — and that, at the Governor’s behest, he carried out the murder for which Giffin has been convicted. The Governor is so terrified by this turn of events that he commits suicide on the spot, saving Giffin.

Notable for its in-depth description of how artificial organs might function, “The Living Test Tube” is a successful melding of two story types that were by now over-familiar within Amazing: the scientific detective narrative, and the horrific tale of re-animated boy parts (see also M. H. Hasta’s “The Talking Brain” and Joe Kleier’s “The Head”).

“The Psychophonic Nurse” by David H. Keller

Susanna Teeple is unable to balance a promising career writing for Business Woman’s Advisor with taking care of her new baby girl, and finds that nurses are hard to come by. Her husband, meanwhile, is unsympathetic to her plight:

Susanna Teeple is unable to balance a promising career writing for Business Woman’s Advisor with taking care of her new baby girl, and finds that nurses are hard to come by. Her husband, meanwhile, is unsympathetic to her plight:

“Take care of her yourself. Systematize the work. Make a budget of your time, and a definite daily programme. Would you like me to employ an efficiency engineer? I have just had a man working along those lines in my factory. Bet he could help you a lot. Investigate the modern electrical machinery for taking care of the baby. Write down your troubles and my inventor will start working on them.”

“You talk just like a man!” replied the woman in cold anger. “Your suggestions show that you have no idea whatever of the problem of taking care of a three-weeks-old baby.”

The story takes place in a future where those with children now have such mechanical aids as vacuum evaporators and curd evacuators; indeed, society’s very philosophy of child-rearing is showing a tendency towards mechanisation. “That idea of mother-love belongs to the dark ages,” says Susanna at one point. “We know now that a child does not know what love is till it develops the ability to think. Women have been deceiving themselves. They believed their babies loved them because they wanted to think so. When my child is old enough to know what love is. I will be properly demonstrative and not before. I have read very carefully what Hug-Hellmuth has written about the psychology of the baby and no child of mine is going to develop unhealthy complexes because I indulged it in untimely love and unnecessary caresses.”

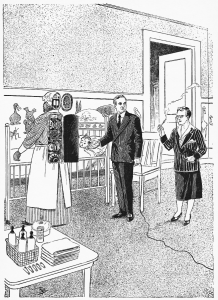

One day, Susanna heads off to a party and leaves her husband to take care of the baby. She returns home to find “a fat, black woman, clad in the spotless dress of a graduate nurse” apparently sleeping alongside the child in the nursery. This, her husband explains, is a machine nurse, made to order:

“She is made of a combination of springs, levers, acoustic instruments, and by means of tubes such as are used in the radio, she is very sensitive to sounds. She is connected to the house lighting current by a long, flexible cord, which supplies her with the necessary energy. To simplify matters, I had the orders put into numbers instead of sentences. One means that the baby is to be fed; seven that she is to be changed. Twelve that it is time for a bath. I have a map made showing the exact position of the baby, the pile of clean diapers, the full bottles of milk, the clean sheets, in fact, everything needed to care for the baby during the twenty-four hours.”

He has also prepared a phonograph recording that will call out the required numbers when neither parent is available. The machine nurse will even change nappies when required: each diaper contains a copper wire that sends an electrical current when wet, triggering a specific noise in an amplifier and causing the nurse to respond as needed.

The custom-made psychophonic nurse is put into mass production, becoming a hit with the public. Watson, an influential psychologist who “wrote that every child would be better, if it were raised without the harmful influence of mother love” is amongst those impressed by the invention. A writer named Henry Cecil (“who had taken the place of Wells as an author of scientifiction”) to predict a future in which all manual labour is performed by similar automatons.

Still another writer proposes mechanical escorts for young men, who have an advantage over flesh-and-blood girlfriends in that they never demand money or trips to the theatre (“He could buy her in a store, blonde or brunette and when he was tired of her, he could trade her in the latest model, with the newest additions and latest line of phonographic chatter records”). Conversely, women could have mechanical lovers of their own, to do the housework while the women are at the office (“For some decades the two sexes had become more and more discontented with each other. Psychophonic lovers would solve all difficulties of modern social life”). The article venturing these suggestions is banned in the United States on the grounds that it is immoral — which only serves to raise its popularity in bootlegged form, even contributing to slang (“Men who formerly were called dumb-bells, were now referred to as psychophonic affinities”).

The invention starts to show flaws, however. As the child begins learning to talk, the psychophonic nurse has trouble distinguishing between deliberate vocal commands and meaningless baby-talk. Despite this, the Teeples order a second such machine, this one modelled upon Mr. Teeple himself and nicknamed Jim Henry, which is capable of taking the baby for strolls outdoors.

But one evening, a blizzard breaks out while the parents are at work and Jim Henry is taking the baby on a trip. Mr. Teeple is forced to brave the storm in an effort to rescue his daughter; he is successful, but comes down with pneumonia. Once he has recovered he finds that the psychophonic nurse has been disposed of and his wife is content to work in the kitchen and take care of the baby.

As well as prefiguring debates about the role of technology in parenting that are still going on today, “The Psychophonic Nurse” makes a point out of showing a future in which feminists have got their way. Susanna is said to be “showing her husband and friends just what a woman could do, if she had the leisure to do it” while writing reviews of such books as Woman, the Conqueror (notably, the illustration shows Susanna in distinctly androgynous clothing, in an apparent attempt to caricature a masculinised woman of the future). The rise of the working woman is depicted in a deeply sour manner, associated with attacks by popular psychologists on motherhood – along with the breakdown of the sanctity of marriage, as illustrated in this exchange:

“You seem rather sleepy in the mornings. Are you going with another woman?”

Teeple looked at her with narrowing eyelids.

“What if I am?” he demanded. “That was part of our companionate wedding contract—that we could do that sort of thing if we wanted to.”

As this was the truth, Susanna Teeple knew that she had no argument…

Naturally, for an anti-feminist story, order is restored once Mrs. Teeple gets back in the kitchen. (The portrayal of the robot nurse as a “Black Mammy” is obviously racist, as well, although unlike the concerted attacks on feminism this seems more like a case of a stereotype being recycled without thought).

Discussions

In this month’s letters column, Norman H. Moore offers some general thoughts on the magazine’s fiction (“Now as to the stories with gruesome plots, which many of your readers also seem to be in doubt about; by all means let us have them if they are worthy of perusal, and not a cheap endeavor to capture interest”) before asking a few questions about physics (“Do light rays, sound waves and various energy rays have to overcome inertia?”).

Emma Ploner also gives some broad thoughts on the publication, including the seeming prescience of Jules Verne: “In the March issue, the story by Jules Verne contains the words airship, hangar, garage, automobile, turbines, twin-screw and many other words that were not even ‘coined’ at the time he wrote. Can you please explain this?” The editorial response: “The Jules Verne stories are translations of the author’s works as he wrote them, and The Master of the World is one of his last efforts. This will explain the use of rather modern words.”

Inspired by the magazine’s stories, R. Muir Johnstone M.D. offers his thoughts on the fourth dimension (“The idea of the mysterious extra dimension is not new to me, but the conception of mechanical contrivances which will operate under such problematical conditions certainly is”) space flight (“our planet is covering space at sixty thousand miles per hour, so that chasing it after missing it would be poor satisfaction even with the aid of gravity”),the shape of the universe (“After trying out the spheroid, cube, and every other form of enclosed space, we will find ourselves baffled”) and theology (“Being a believer in Almighty God, a Spirit-World, and the human soul, I see no place for these within the scope of the physical three dimensions. They belong to the Fourth or possibly a Fifth Dimension containing elements of ‘spiritual substance,’ a term borrowed from Swedenborg”) His overall assessment of the magazine’s contents is favourable: “On the whole. Amazing Stories is far preferable to the average current fiction magazine with their preposterous repetition of modern roundtable stuff.”

Herbert L. Shepard compares H. G. Wells unfavourably to some of the magazine’s other writers:

Wells’ stories, I think, lack what you might call human interest. They read like a description or a catalogue of parts or events. The idea I am trying to convey can be better grasped by comparing Wells’ stories with the two stories The Lost World and The Moon Pool which appeared in Amazing Stories. I think these two tales are among the most charming and interesting I have ever read. Treasures of Tantalus is of this sort, also. In these stories the author has the knack of making you feel as though you were right on the spot and going through the adventures with the characters. I do not think this is so in Wells. When I read him I always feel as though I am walking around in a trance. I would like to see more stories by authors

Amazing had not reprinted Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World; Shepard appears to be thinking of Burroughs’ The Land that Time Forgot. “I also think the covers could be a little more conservative in keeping with the high class standard of the magazine”, he concludes.

B. K. Goree Jr. encourages Amazing‘s readers to get a copy of Gernsback’s Ralph 124C 41+ (“one of the best scientifiction stories I have read”), argues that the physics in Earl L. Bell’s “The Moon of Doom” contradicts the theories of Sir Oliver Lodge, requests reprints of stories by Morgan Robertson (“‘Beyond the Spectrum,’ written twenty-five or thirty years ago, was one of the first and most original stories to be written about the ‘Death Ray’”) and pre-emptively defends Wells’ When the Sleeper Wakes from criticism (“those of you who are rabid scientifiction readers like myself, please don’t criticize Wells too much for plagiarizing from ‘Caesar’s Column.’ What if he did?”)

Harold F. Osborn is another who dislikes the magazine’s covers (“I always tear off the cover of my copy, for I feel sure that to exhibit it would be a detriment to my prestige among my friends.”) The editorial response to this complaint is remarkably upfront: “The publishers are fully convinced of the fact that the covers are not artistic or ethical, but this does not affect them in their decision at all, for the simple reason that experience has taught that only ‘flashy’ covers are easily seen when displayed on newsstands… If Amazing Stories had a circulation of one million copies and was twenty-five years old, it would be simple to adopt a more ethical cover. Right now, that is impossible.”

On a similar note, Madlyne A. Riegel finds the magazine’s title objectionable: “The name puts it in a class with magazines called ‘Ghost Stories,’ ‘Weird Tales,’ ‘Detective Stories,’ ‘Wild West Stories’ and the rest of that trash… I loathe the sort of fiction suggested by the titles given above.” Despite this, Riegel has done a little to boost the publication’s popularity: “I am managing a little restaurant on the edge of the city, and have everyone working there reading Amazing Stories, so that those who come in wonder what it is all about, and pretty soon they are doing it too.”

J. A. Netland, continuing a letters-column conversation with C. P. Townsend, poses questions about evolution: “Why does not a Genius produce a Super-genius? Why are the children of various types of Genius mediocre?”

G. R. Brackley points out paleontological errors in Hal Grant’s “The Ancient Horror” (“The writer stated that the saurians roamed the earth during the Mesozoic era, some five hundred millions of years ago. Pirsson and Schuchert of Yale state that the Archeozoic era began about 500,000,000 years ago. This would make the Mesozoic occur about 85,000,000 miles [sic] ago.”)

B. N. Boston credits the magazine with inspiring him to study medicine (“I am firmly convinced that had it not been for its splendid work I would still be working in a mill”) before going on to request reprints of the Frank Reade Jr. stories by Luis P. Senarens. Meanwhile, seventeen-year-old J. M. Walker describes how reading Ray Cummings’ “Around the Universe” inspired a desire to study astronomy.

Harry A. Barnes (a self-proclaimed “writer of humorous drivel, that is published without credit to me”) objects to what he deems unnecessarily harsh criticism in the letters column: “Scientifiction is the result of research and study and we are not qualified to find any fault unless we have indulged in a greater amount of study and diligent research than has the author.”

Arthur Wellward, a reader from Manchester, mentions the difficulty he has in obtaining Gernsback’s magazines in England; he also praises a number of stories, while deriding Hicks’ Inventions with a Kick (“They reminded me of the old Keystone, pie throwing comedies, and bored me just as much.”)

Henry Goldman requests more pictures (“I would suggest that each important and interesting action in the story should have an illustration. By means of these pictures the reader could see every move in the event besides reading it. Now to center on the stories”) and simpler terminology (“I do not happen to be a scientist and it is very hard to understand the terms the authors apply to conditions or apparatus which, most likely could be expressed in a simpler manner”).

Finally, two of the readers provide newspaper clippings, a tradition that had been absent from the column for a while. Harold Cohen sends a report about the display of a revolving house in Paris, which reminds him of Hicks’ Perambulating Home. Meanwhile, Charles Lawrence sends a clipping from an unspecified periodical discussing naturalist Marguerite Combes’ observation that ant hills sometimes have “fire departments” (“She placed a lighted taper on a hill and a battalion of ant firemen extinguished it. Some squirted liquid formic acid from their jaws on the taper. Others tore at it. Many perished. One hero dragged another from danger.”) Lawrence connects this to Francis Flagg’s “The Master Ants”.