Homeworld of the Heart

from Chronicles of the High Inquest

excerpt

Author’s note:

In 1979, stories set in the Inquestor universe started coming out, first in Analog, then, mostly in Asimov’s, and one rather memorable one in 1984 in Amazing. These stories seemed to get a lot of attention at the time, and they were assembled into a sort of tetralogy, but the problem is, the first two books were published by Simon and Schuster, and the next two by Bantam, and by the time the first two were published by Bantam, the second two had gone out of print.

Thus it was that despite many raves from reviewers as exalted as Ted Sturgeon and Orson Scott Card, the books were never all available at the same time from any one publisher.

Over the past decades I have been getting letters from time to time asking if I could revisit this universe, abandoned when I moved more into the horror end of the field. The word inquestor. which I invented in order to sort of hint at the Inquisition without being the Inquisition, has even been appropriated by others — appearing, for example, as an occasional addendum in the Star War universe.

After about thirty years it transpires that I’ve realized there is quite a lot more to tell. At least another trilogy’s worth — maybe two trilogies.

In Homeworld of the Heart I’ve reentered the universe more or less in the middle, going back to the childhood of one its key personalities, the bard Sajit. He appears in many of the stories already and there is a life arc stretched out for him in the preceding four books, but a great deal else is mystery.

I’m releasing this excerpt as a way into the series even for people unfamiliar with it. If you enjoy, consider reading it a chapter at a time as I write them by becoming a patreon supporter (patreon.com/spsomtow). I’m also serializing it in a personalzine, Inquestor Tales, which you can buy on amazon in both print and kindle, and each issue comes with a lot of fun ancillary material; essays, original versions of short stories unseen in three decades, and a linguistics essay by the mysterious Professor Schnau-en-Jip which helps to analyse the texts in the High Inquestral language.

Amazing has made a dramatic intervention in my career a number of times in the past. I was a young unpublished writer taping quarters to manuscripts as demanded by editor Ted White in the 1970s. When Hank (now Jean) Stine became editor of Amazing, he released a novelette of mine, The Last Line of the Haiku, an unseen story which had evolved into a novel. George Scithers published several of my stories in Amazing, including the comedic Aquila series, and indeed, one of the stories in the Inquestor universe, The Comet that Cried for Its Mother — about thirty years ago.

So it’s with a great sense of history that I submit this excerpt for your enjoyment. The Inquestors are returning — and with your support, they might stick around longer.

Prologue

Sajittang

… and there was also a village named Sajittang …

… far from the great central worlds of the Dispersal … at the opposite end of the galaxy from Uran s’Varek, the sphere of the Inquestors that surrounds the black hole at the galaxy’s heart, where the stars are packed so thick that their scattered light, through thousands of klomets of atmosphere, blends and blurs to a seamless radiance … whose thinkhive contains the thoughts of a billion billion souls …

… far from Gallendys with its pyramidal twin cities stacked one upon the other like cones of pinwheel fire, where the windbringers fly blindly and sing music of searing light …

… far from Shtoma, where they dance on the face of the sun …

… far from Aëroësh, where the dust is alive and the living turn to dust …

… far from Periput, from Bellares, from Billoras, from Bellbaros, from Anthalafré and Ugoradé, from the chimes of Chembrith, from the feasting fields of Fiünn and the forever forests of Fáraklanth …

Sajittang was the only village on this world; a single pair of displacement plates linked it with a starport, to which few pilgrims came. When they came, they would come to the shrine in Sajittang, where an old whisperlyre lay on a plinth beneath a protective forceshield.

This shrine, this starport, should not even exist, for the world has fallen beyond. But pilgrims did come, from time to time, and they would visit the whisperlyre, guarded by orphaned srinjids, and they would meditate a while, or kiss the barrier of force as if to get closer to the whisperlyre, or try to write a poem as they sat in the village square.

But one day, there came a visitor more important than most.…

***

Varezhdur, palace of dreams, hung in the night sky like a spindle trailing threads of gold, eclipsing the moons themselves. And from the palace a floater delicately descended.

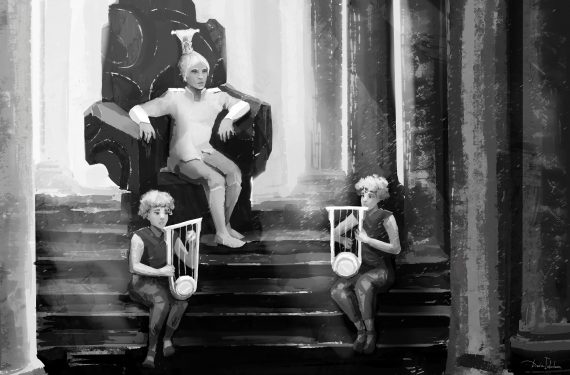

An old man flanked by srinjids watched. The old man had waited all his life for this moment to come. He knew that one day a floater would come, and who would be riding it. What surprised him was that the man was alone. It was a figure he dared not look at closely; to gaze such a one directly in the eyes had been known to bring immediate execution. But he was alone. There was not even a quartet of childsoldiers guarding the four corners of the railings, the minimum escort for one of such power.

The floater moved in a completely straight line, though there was a wind, whispering as it scattered dead leaves over the flagstones.

The floater moved in a completely straight line, though there was a wind, whispering as it scattered dead leaves over the flagstones.

“Now,” said the old man to the srinjids, “begin your song.”

Childlike, one srinjid spoke and another answered. The two voices harmonized almost without intent. From a hut behind the shrine, another voice came, then another, speaking of inconsequential things, yet each inconsequently snippet of speech was an ornament, a trill, a heterophonous melisma woven into an overarching music.

The srinjid’s song was of necessity complete; their city on Uran s’Varek long destroyed, but a handful of refugees had been rescued. Here, in Sajittang, they thrived, but their song was not a perfect melding of a million voices; it was the ghost of a song, a snatch here, an echo there; it was a memory of what was once beautiful, not the beautiful thing itself. Yet it had its own melancholy beauty, even in its imperfection.

The floater touched the flagstones of the square, old stucco stained with age, veined with a purple moss from which one could distill a zul-like liquor. The old man had not seen any pilgrims for a long time, years; this was no ordinary pilgrim. The floater’s skin dissolved. The old man prostrated himself. It was a moment he had rehearsed for all his life, yet now that it had come, there was an emptiness to it; the time when such gestures had meaning was long past.

Through unkempt white strands of his own hair, the old man saw the shadow of a shimmercloak. The coruscating pink against deep blue. The cloak that was a living thing, gliding, flowing, intertwining flesh. And feet; immaculately manicured, bare, but painted with protective shieldskin; this Inquestor was old, too, but for an Inquestor, to be old is different different.

“Hokh’Ton,” the old man mumbled, then waited to be spoken to.

“What are you called?” Strangely high-pitched, a child’s voice, almost, though the flesh was withered.

“I am Tash Toléon,” he replied, “0f the Clan of Rememberers. I guard the tomb of Shen Sajit, the voice of the cosmos.”

“Stand, Tolé,” said the Inquestor. “My feet do not have ears, and I’m too old to bend down to your level.”

Toléon motioned for one of the srinjids to bring a stool. Another fetched some of the juice of the moss. “Forgive me,” Tash Toléon said. “Seeing you in the flesh—”

“So you know my name,” the Inquestor said.

“Of course. You are hokh’Ton Ton Elloran n’Taanyel Tath, Lord of Varezhdur.”

“What else do you know?”

“That you knew Shen Sajit when you were children. That you showed him favor beyond all measure. It was even said that he was your lover.”

And Ton Elloran smiled a little at that, saying only, “Love has a million shapes.”

For a while Elloran listened to the singing of the srinjids. “I didn’t know the remnants of that city were here,” he said. “It is … painful to hear. You never heard their singing city, of course.”

“No, hokh’Ton.”

“It’s like hearing a ghost.”

“Everything on this world is a ghost,” said Toléon. “Including myself, for I exist only to be your rememberer.”

He nodded to the nearest srinjid and the song began to die away. Perhaps, he thought, I should not have made them sing. The Inquestor will be sad.

“More sad than you can imagine,” the Inquestor said, as though he had heard Toléon’s thoughts. “You don’t know how their city was annihilated. You cannot understand Arryk’s rage at my love for a shortliver.”

Toléon still avoided the Inquestor’s gaze, but he could sense that he was looking away. He dared to look up a little.

The Inquestor was looking at the whisperlyre, that relic, that object of occasional worship, locked in a dome of force. Presently he ordered the old man to unlock the dome.

Toléon muttered a subvocalization that may not be revealed, and he was able to reach in and touch the relic. It has strange, he thought, that he had never touched it in his life. There was a kind of tension behind the field; when it dissolved, dust seemed to settle on the instrument, where before it had been suspended in a quasi-vacuum. He brought the instrument to the Inquestor, kneeling to present it. When Elloran touched it, there came a wheezing, jangling sound and a sudden rainbow flash that dissipated into a white mist.

“You should leave us, perhaps,” said the Inquestor.

And Tash Toléon saw that the godlike being was weeping. “An Inquestor—”

“Does not weep!” Elloran said softly, yet did not cease to weep. “Do you still think I am what you thought me? Do you not know that I have cast aside my power, given away the worlds I owned? Even Varezhdur is not mine; I gave the palace that sails through space to Ton Siriss; I travel by Varezhdur only through her grace, because she did not want me completely cut off from the life I knew.”

Toléon saw that the old Inquestor could not be comforted, certainly not by a Remember’s words. So, as unobtrusively as possible, he left; and there he was, an old weeping man in shimmercloak, on a stool on a lonely planet, clutching an instrument that had not played in a century or two.

***

Subjectively he was no more immortal than any of the trillions of the timebound. Yet Elloran had spent so much time in the space between spaces that to a man such as this Rememberer he must have seemed eternal. How often had he travelled from one world to another, to return and find the first world fallen beyond?

Even so, as his hands held the leathery frame of his old friend’s whisperlyre, he could imagine what it was like to live in little steps, to grow old, to die, in a heartbeat. Those moments were a heartbeat away. The meeting in the bowels of a doomed starship. The journey to find the Rainbow King, and the hunting of the first utopia. The voyage to the world of the dust-sculptress, who love dust more than she could love an Inquestor. And all those momentous events framed in the songs of Shen Sajit.

My life was lived in earshot of Sajit’s great poetry, Elloran thought. Sometimes all Varezhdur resonated in sympathy to the plucking of a single string of the whisperlyre.

He moved his hand over the strings. Only a jangle came forth. He touched the fingerboard, still sensitive; it responded to the slightest change in pressure with a cascade of color, for, like the shimmercloak he wore, it was on some level a conscious being. It knew that the one who touched it was not Sajit.

***

… a bone-thin boy, laughing …

The streets of Aírang, city of pleasures. Turning a corner. The smell of mulled zul from an unseen alley. Dancing pteratygers in the sky, images woven by giant dreamweavers clamped to the tops of minarets …

Elloran stirred. It was one of the images that came to him often now, though it could not be a true memory. So often Sajit had spoken of growing up in the streets of the pleasure city. But Elloran had not known Sajit in those days. Only later, when they had come together, in adulthood, to forget things that cannot be forgotten.

The whisperlyre clattered on the flagstones.

Blurred light. A buzzing sound. The strings, perhaps, or insects of the night. Then the servant of the shrine, that fawning Rememberer, was back, with a tray of fruit and pastries.

“Forgive me, hokh’Ton. I know you requested aloneness, but.…”

“Yes, yes. Where does one lodge in this village?”

“There is an Inquestral guest-house. It has never been used.”

“We shall go there.”

“But first, hokh’Ton, there is something I must tell you.”

“You have something to tell me? Curious.”

“Yes, Lord. For the whole Dispersal knows that you knew Sajit as you know yourself. And the whole Dispersal knows the stories and calls them true: songs about them are sung, actors play the bard and the Inquestor in operas, in servocorpse dramas. We know of the hunting of your first utopia, of the pursuit of the woman in the dust, of the building of Shentrazjit and creation of the srinjid symphony; of Sajit’s death and Arryk’s rage and of your grief that lasted a century and more. And it is known throughout the Dispersal of Man that one day you come to this village and sit in front of this shrine.”

Elloran listened, for the last sentence he had not heard before. And now he listened intently.

“I was given the duty of waiting for you, said Toléon, as was my father before me, and his father. Because of this duty, my grandfather elected not to be taken up into a people bin when our world was selected to fall beyond. And he waited in this sanctuary, knowing one day you must return.”

“And I have,” Elloran said. “But what must you tell me?”

“I must tell you, hokh’Ton, that everything you ever knew about Sajit was … inaccurate.”

“Do you mock me?”

“Never, my Lord. But you must believe me when I tell you that when you crossed the world of the dead to confront the heretic Inquestor, the one who shared your journey was not Shen Sajit. When you quarreled over a woman, your rival was not Sajit … or, perhaps, he was, but at times he was not. It was not Sajit for whom you made the singing city, nor Sajit whose body you sent there, swooping down in his golden hearse, to be interred in song. Sajit lives, though he does not live. You shall see him again, you shall see him yet you shall not see him. Because, Ton Elloran n’Taanyel Tath, I am here to be the memory you never had. I am here to speak of the Sajit you never saw. Because, my Lord, there were two Sajits.”

***

And thus it was that Tash Toléon began to speak of a boy named Sajit. And because he was a trained Rememberer, the boy sprang to life in the telling, and Elloran saw everything he thought true torn up, sundered, reassembled into another truth.

“Once upon a time,” he began, “the name of this world, which now has no name, but only a set of coordinates, was Alykh, and it was a planet of great pleasure cities. In this city an orphan beggar boy named Sajit lived, singing in the marketplace with a broken whisperlyre, until one day …

“Ah, but before that pleasure planet, in the same cooridnates, there was a world named Urna, a world of few pleasures, and fewer cities; mostly there were villages, tiny, impoverished. And in one those villages there lived a boy named Sajit, ”

***

So the telling began. To hear the Rememberer’s voice was to gaze into a mirror with no edge, and to see the mirror mirrored and re-mirrored, unto infinity.

And the mirror of the mirror’s mirror was the soul’s soul’s soul.

Book One

Book One

The Singing Moons

One

Attembris

A chill gray space.…

A pool of light in a deep dark forest …

In the dream it is always the same, the same circle of attenuated starlight, the same musk-drenched odor of vanjeris leaves, the same breeze, barely felt, bearing the scent of a lost city. And the singing moons.

The place can be visited only in dreams because like so many places he has known, it has fallen beyond in the great game that is played between those near-immortals whose caprices control the destinies of the million worlds of the Dispersal of Man. And when a world has fallen beyond, it lives only in song, and song belongs to the poets alone.

But oh, oh, oh, the poet cries, I want to enter that circle once again, to touch the silky strands of the vanjeris and see the rosella petals dancing in the breeze, in the column of chill gray light. And he dreams again. And dreaming he returns always to this place….

The place he dreams of is just outside the village of Attembris. And where is Attembris? you may well ask. For the place does not live anymore, not even in song and story. Yet for one man it is the very center of his homeworld, the homeworld of the heart.

The village itself was barely deserving of that name, being a mere cluster of houses around a displacement plate that linked to the central square of a slightly larger village, whose square in turn was linked to that of an abandoned temple. Abandoned, for religion had not been in vogue for some centuries.

Once, when he was much younger, he had set foot in that temple. That’s where he first saw the woman cloaked in shadow.

The way she looked at him … she was close to him … in a way that even his own mother was not.

“Who are you?” he asked her.

But she did not answer, and indeed, when he looked again, she was gone.

From time to time, he dreamed of her.

***

Their house was the last house in the village, just outside the gate. The gate opened out onto a pathway, but that pathway was subsumed in moss and weeds, for pathways too were no longer in fashion since the network of displacement plates had become operational.

From the boy’s bedroom, the forest was but a single step away. Thus, darkness and mystery were always within his reach.

Since he could barely walk, he had learned to go there when he was afraid, or when he simply needed to be alone. He had learned to count the thickets until the spaces broadened and there was a ring of stones, perhaps made by men, or left behind by the Inquestors, perhaps even from the time before there were humans in this world.

When he came to this place, he could always hear the music. Especially when at least three of the moons were full. It seemed to him that the moons could sing. It was a manystranded singing. Each of the moons had a separate voice. They sang in a pure and absolute harmony, making chords that he had never heard from the village choir, when they met each tennight to sing the Dhelyá Sarnáng, the anthem to the High Inquest.

And what did the moons say to him?

They said: You are not who you think you are. You are a different person. This is not your world.

It was only when he was a little bit older, that he realized the singing came from within his own mind. That other people did not hear the music the way he did. And that he could reproduce that music at times, making new sounds that the world has never known. He could pluck the sounds from his mind and make any instrument repeat them, whether it was the panorchestrion in the village square or the old whisperlyre that had been his grandfather’s, or even a bunch of twigs and an ystrell-skin stretched over a jar. They called it a gift.

Because of this gift, they told him, we have to protect you. You cannot be called the way other children are called. We’re going to have to find a way to hide you when they come for you.

“But why will they come for me? Who are they, that I must be so afraid?”

“You don’t need to know that yet.” That somehow always ended the conversation.

For the world that the boy lived in was a safe world that had few terrors. Children were not afraid. They played all night and knew nothing of demons, ghosts, or vile spirits. On the whole, the people of his world were warm and openhearted. It was not a world that had frequent wars or conflicts. In a way, it was a world that verged on Utopia.

But the boy learned very young that the word utopia was not to be uttered. It could not even be thought. For the edge of utopia was a good thing, but beyond that edge lay annihilation. A utopia would always, one day, fall beyond. The boy had learned in school that “the breaking of joy is the beginning of wisdom.” Everyone knew that.

He may have been too young to wander around in the forest late at night, but there were times when he could not help himself. They were the times of strange, disturbing dreams; of twisting and turning; of wondering about the things that the adults would not speak of.

In the night, in the forest, in the clearing, by the gray misshapen boulders, in the light of the dancing moons, that was music. That night he heard the music so clearly that he thought a visiting klazmurah might be in the vicinity. They did come to the village from time to time, on the way to a bigger city, to a princeling’s court, even on the way to the residence of the High Inquestral Legate. But no. There was no one else there. This music was in the air itself, was woven from strands of the shifting moonlights, and the wisps of mist. And yet, he could even pick out a line or two of melody, weaving in and out of the unearthly harmonies.

He could almost hear the words.

And before he knew it, the words were leaving his lips, words barely understood, yet fully formed.

Den Táthes eyáh

Den Sírana.

The words he formed were words of the Highspeech, a language no one spoke, but which you had to learn in school. He sang about the trees and the wind and the dancing moons; the intertwining harmonies he heard enveloped him, buoyed up the song with its meandering melismas. Surely this was an ancient music such as might be heard streaming from a malfunctioning song cube.

It is neither the winds

Nor is it the moon….

“That is true,” said someone. “It’s you, just you alone.”

The rest of the song died on his lips. Suddenly the woods and the air were silent, and the light was only light.

“Who’s there?”

“What do you mean, who’s there?”

Nothing is dangerous on this world, the boy told himself. He turned. The clearing was empty. The ancient boulders … were they glowing a little?

“Come out and show yourself,” he said, trying to sound like his father. “My parents are important in Attembris. I don’t scare easily.” By now he was very scared indeed, and eyeing the escape path anxiously.

The forest laughed.

The laughter, like the music before it, seemed to come from the very air, from the rustling leaves, from the branches stirred by the chill wind. And then the boy saw its source: a man was emerging from the shadows between two trees. As he materialized, he went on laughing. Finally he seemed to notice the boy’s discomfiture.

“I’m so sorry,” he said. “I forgot that I was invisible. It’s easy to forget to turn the thing off. In the city, one becomes used to being invisible.”

“I’m not afraid,” said the boy. “I was just startled. Where I come from, people don’t just appear out of thin air. It must be a city thing. Is this your land? I’m sorry! I shouldn’t be out here.”

“And why not? On a night like this, in a lit clearing beneath the Dancing Moons of Urna, a sight well celebrated in song and story?”

“What are those words I sang? Is it an ancient song I learned and somehow forgot until tonight?”

“Not at all,” someone said. “It’s completely new. And miraculous.”

The man laughed again. He was not old, not young. He wore a simple wrap cloth over one shoulder. His kilt was gray. You had to look closely to realize that it was handwoven, and that the belt was a living, opalescent serpent with red eyes, and a forked tongue that flecked the man’s bare midriff, perhaps enjoying the salt in his sweat. Yes, a casual glance would have revealed nothing, yet here, in the light of the dancing moons, given the fact that he possessed a privacy shield, which would have cost his father a year’s salary, the boy knew that this was no ordinary villager who happened to be taking a walk in the woods.

“Are you a senator? A counselor? A Princeling?”

“Princeling!” The man laughed again. “My, what big eyes you have.” But Sajit saw a big lapis ring with an intagliate design of mating serpents, and sensed that it was the insignium of an important family.

“I’ve learned all the formal modes of address,” the boy said. “I never thought people actually used them.”

“And who, then, are you, who fill the forest with such haunting melody that even I, who stop for nothing, should stop to listen and to know, should pause invisibly in this wood to hear him?”

The boy looked into the man’s eyes then, and knew that this meeting was the most important moment of his life. In school, his classical tutor Arbát had taught him that lives are journeys and there are crossroads on those journeys and on these crossroads one may meet a traveler one would never meet on one’s own road. And these travelers can change lives. This traveler was one such, he knew it. “You’re going to change me,” he said.

“You are wise,” said the man, “to say something such as this to a man whose name you not even know. And who does not even know your name.”

“My name? Nobody asks my name. I’m too young to have a name, really. But in the village I am called Sajit son of Areon darSajit the keeper of the village thinkhive.”

“Then I greet you, Sajit-without-a-Clan. You shall hear from me again. And in the meantime, I give you this gift.”

And plucked a song cube out of the empty air. Tossed it to the boy. In the light of the dancing moons, it seemed almost alive.

Sajit squeezed the cube in his hand, releasing the hidden music. Sounds poured out. Such sounds! Oh, he had heard the wind singing. He had heard the melody that streamed from the intertwining of the light of all those moons, the dark ones and the pale. This was different. It was perhaps rooted in nature, but it was far from natural. This music has been composed.

Which meant that he did not come from some village tunesmith, but from an artist of one of the great courts.

Sajit wanted to thank the man, but he already disappeared. Perhaps he was still there, but if so he had switched his privacy shield back on. So Sajit sat for a while letting the music play, not daring to sing again for fear that someone was eavesdropping. For even then, even as a child, he knew he did not want strangers to hear his songs until they had become perfect.

And so he allowed the strains of the artificial music to seep into his very being, and slowly he drifted back into one of those strange dreams, the ones had been having all year, the one about starships and exploding planets and the long cold silences between the stars.

And amongst the stars, there stood a woman cloaked in shadow, and he was whispering, “Tell me who I really am.”

•••

When he woke, it was already morning, and he knew he would be in trouble. He made his way home in a great hurry, barely lingering at each displacement plate. Even so, he arrived at his bedroom window too late to be able to climb back in discreetly. The family servocorpse was already bustling about the room, folding up the bed so it could be put away in the drawer, and injecting the lamps with glowworms. Luckily the servocorpse was not an intelligent model, and would be telling no tales.

But when he reached the breakfast circle, the whole family was already gathered, and the morning meditation seemed to have been interrupted.

“Mother, I —”

Ina desAreon put a finger to her lips and turned to Sajit’s father.

Usually, Areon darSajit was taciturn in the mornings. But this time Sajit’s father spoke. “I don’t think it’s necessary for us to ask where you spent the night, my son. Whatever happened, you seem to have brought our family immense favor.”

Sajit looked at the center of the breakfast circle. There was a globe. It glistened. It floated above the ground by some fancy antigrav mechanism. The globe carried the seal of the Senatorial House of Urna.

“We are asked to keep the contents of this globe a secret,” his father said, “but I think it only fair to tell you that it is a doppling kit.”

“But they only make those for the Royal Family!”

“Exactly. We have always said that we must find a way to hide you if the time were to come, and the means has suddenly been provided, and by the highest provider on this planet.”

“We are proud of you, son,” said Ina, “even though we don’t quite know you pulled it off.”

Sajit looked at his mother and father, then at his two younger sisters Chanika and Vimla. Nobody answered him. It was clear that the honor was so unprecedented, so exalted, that it was almost beyond comprehension. Whoever the man was, he had deemed the boy Sajit so important that a clone would have to be made, and that clone kept hidden away just in case the Inquestors came.

Sajit, of course, never seen an Inquestor. To see one when is rare as to be visited by one of the gods of the ancient religions. He spoke their language of course; everyone had rudiments of the high speech in school. And he had learned a little of their history from his classical tutor, although the history of the High Inquest was not a regular subject for a village school.

He knew that they came only once in a decade or two, sometimes only once in a century. But when they came, they always took away the children. For far away, on the other side of the mysterious overcosm, wars were being fought, planets destroyed, worlds were falling beyond in an eternal dance of creation and destruction. And wars demanded children. Only a prepubescent child, his reflexes honed to the utmost, could manipulate the streams of deadly light from implanted laser-irises. Even after millennia of human invention, the child was still the most efficient killing machine in the Dispersal of Man.

The presence of a doppling kit in the house meant two things. One: Inquestors were coming. They were probably coming very soon. The comings and goings of the High Inquest were known only to the Senatorial Council. Two: the preservation of Sajit of Attembris was of crucial importance to someone in a very high place.

Doppling kits were of course forbidden. Even natural twins were taboo in some villages, and one would be selected for a painless devivement, to prevent abomination. Doppling is against nature, that was a precept everyone repeated in school. The individual can be but one.

But there are some people in this world as in every world to nothing is forbidden.

Ina looked at the artifact with both exhilaration and dismay. “It’s a curse,” she said. “But it had to happen. One way or another. We always knew.”

But his father said, “Perhaps we need to see this in a better light. Perhaps we should see this as an emblem of hope. If the Inquestors are truly coming, many families in the village will shed tears. But our family may not. There is opportunity here, opportunity as much as risk. Sajitteh, how old will you be come summer?”

“I haven’t been counting, father.” The morning zul was getting cold. “My teacher says I’m too busy dreaming to count the years.”

“Next year, he will be ten,” his mother said. “Twelve and it’s too late, we’ll be safe.”

But if they are this concerned, Sajit thought, we must not be talking about next year.

They ate in silence for a long time. Sajit wondered when they were going to start up the doppling kit, but no one mentioned it. That day, when he returned from school, it had already been put away somewhere, and he dared not ask where.

***

That night again, he dreamed of the woman cloaked in shadow. She stood beside his bed. In the dream, he said to her, “Are you my mother? Because … sometimes I don’t think these people are my real family.” He thought he saw her smile before her whole face vanished once more into shadow.

***

And the next day he had no time to think of doppling kits, because he had been summoned to the Palace of a Thousand Snows, and his entire family with him. Even his tutor Arbát had been hired away from the village school and assigned to Sajit alone.

They brought almost nothing with them from the old home. But one thing they did bring. It was something from an old closet, something he’d never seen before … pieces of an old whisperlyre.

“We’ll hang this in a place of honor,” Areon said.

“Yes,” said Ina. “To remind us about …” But she stopped herself.

Something was being kept from him. A piece of a puzzle. Like the woman in his dreams, like the man in the forest.

Of the summons from the palace, Sajit’s father said only, “I used to think it was such a pity that you had no friends, but that too was a blessing. When we left Attembris, you had no one to weep over.”

Two

Nevéqilas

Nevéqilas blossomed in the sky, a crystal chrysanthon on a glass stalk that stretched far above the minarets of the city of Shírensang, the Inquestral seat of Urna. It was a small provincial seat of only a million souls; the reach of its demesne was only a single world, one inhabited moon, and a few colonies dotting the sparse empty space between world and moon. Still, it was the biggest city Sajit had ever seen.

Sajit’s family were lodged not far from the crystal stem that led up to the palace. It was so close, in fact, that there was no displacement plate connecting it to the square; it was about half a klomet to walk, down a real street with paving stones, not weeds, lined with shops, even; the brief walk was like a journey into a fairy tale.

The apartment was not a pretentious one, but compared to their home in the village it was in itself palatial. Each of the siblings had a separate room, and there was a music room which was connected to his own bedchamber. The breakfast circle was surrounded by simulated forest, so that they were always linked to Attembris.

They hung the broken old whisperlyre on a branch of the holosculpt tree of the simulated forest, and sometimes it swayed in a simulated breeze and let forth a simulated sighing.

There was another apartment, in a slightly poorer neighborhood, for the tutor as well; in fact though Arbát lived alone there, he had almost as much room as Sajit’s entire family. Arbát’s lodgings were further from the palace; it took a few displacements to get there.

Sajit assumed that on coming to the metropolis he would immediately be summoned into the presence of the mysterious lord who had discovered him; in fact, Arbát informed him, that was not going be happening soon … not in a month, a year, or even ever, for the lord had, it was rumored, many protégés, each one kept carefully isolated from the other.

Instead there was going to be training. Training of a kind unimaginable in Attembris.

There was going to be some kind of routine now; whisperlyre lessons, the history of the clan of Shen, the great poets’ clan, to be memorized, although Sajit could not dare to dream of one day being inducted into it himself; and formal instruction in the arcane theories and philosophies of music. And regular meals.

In the breakfast circle there were four double-purpose cushioned benches such as families use to store their belongings. Three of the benches contained eating utensils and dishes and a decorative light sculpture that would be used as a table centerpiece when the tutor, or other guests, would come for breakfast. The three benches opened easily with a subvocalized command. The fourth was always locked and Sajit thought better than to question this. His parents had many secrets.

Everyone had secrets. To be a child was to be kept continuously in the dark, to be told that such and such would be known “in due course” or “at the right time.” The locked storage bench was one such mystery.

He did not question it until his curiosity got the better of him….

Which happened within a single tennight.

•••

His parents had gone to the corpse depot to find more adequate help, as the primitive servocorpose they had brought from the village would never be able to maintain a city dwelling properly. Corpse depots are soulless by their very nature, and never a favorite haunt of the boy’s.

The whole family had gone, but Sajit was to see Arbát for a discussion of transstellar monody; it was a dull subject, and when Arbát’s messenger arrived to say that Arbát would be indisposed for the day, Sajit was glad of the relief.

He was alone in the dwelling for the first time, and he thought about the locked storage bench.

He knew he should not think about it, but he could not help himself.

For an hour he entertained himself by practicing scales on a mnemokitharon, an instrument designed for discipline, not music; one had to play each scale correctly, at the right tempo, and in every permutation from direct through to inverse through to retrograde; a wrong note was rewarded with an unpleasant tingling, like an insect bite.

It wasn’t long before Sajit found himself wandering back to the breakfast circle. And gazing at the four storage benches, of which only one was locked — the one he himself usually sat on every morning.

He knelt down and knocked on it. The material was natural, some kind of old wood. That in itself was curious; organics had been passé for decades.

He knocked.

Knocked harder, laughing.

From inside, something knocked back. His heart skipped a beat. It’s haunted, he thought.

Sajit ran to his room. He couldn’t wait for his family to get back, and he babbled all through the next meal, boasting of the scales he could play.

•••

The new servocorpse was a talking model, but of a rustic demeanor and limited vocabulary. They decided to call it Bo, even though the naming of servocorpses is fraught with danger, for one might come to think of them as people. Bo was not a friend, but in Nevéqilas Sajit had not yet found friends. So it sufficed.

Days more passed, in the company of Arbát mostly. A classical music education mostly begins with the mnemokitharon, and the memorization of long sequences of scales, as well as the philosophical, historical and emotive basis of each. Each of the four hundred and seven divisions of the octave had a name, and the notes were classified by color as well as by the degree by which they bent away from the thirteen basic tones.

And Sajit, you knew all these things by instinct, who grasped the roots of music with such ease, found the naming tedious, and wished always to get to the creative part of the lesson, often delegated to the last few minutes. It did not take long for Sajit to understand that he was more gifted than his teacher.

Arbát was also something of a dreamer; often Sajit could smell the dreamstuff on his breath, and often Arbát drifted into a reverie, as he had consumed too much. He was, Sajit realized, bitter — though why, it was hard to know, since he had now been rewarded with such great fortune, a city dwelling, a stipend, and only a single pupil to teach.

Unless it was his pupil’s talent that made him bitter.…

But Sajit did not want to consider this as he practiced the scales on the whisperlyre over and over, memorizing the assigned affect of each scale and the list of nuances of each subdivision, while Arbát stared into the middle distance, pausing now and then to place an admonishing finger upon Sajit’s fret-matrix … “No, no, the second dha in the series should be flatter … flatter … listen harder won’t you.…”

The days went by and Sajit was home alone again, and his thoughts returned to the storage bench. And once again he crept into the breakfast circle. And knocked on the old wood. Which knocked back. He tried a cross rhythm he had just been practicing, his left index finger tapping fives and sevens while his right hand hit fours with the edge of his palm.

The same rhythm, very faint, came back at him from deep inside the wood. And in his dreams, that rhythm came again.

•••

… and there would come the dream again, and more fragments of the song …

It is not the wind

It is not the moon …

The words were becoming more clear now. But why only a single moon?

The snow is aflame,

yet the heart has frozen.

I am not I.

The words were of flaming snow, and a single moon. This was not Sajit’s world. But Sajit had never seen another world.

In the dream, too, he would see the storage bench … the box. And he knew they were linked.

***

One night he woke, and knew, somehow, that he must find out what was in box. He felt this knowledge inside himself, as though something in the storage bench were calling out to him, knew his name, even. It must be some kind of musical instrument, he thought, something powered by a microthinkhive so dense it could predict his very thoughts.

The family quarters were equipped with amnio-hammocks, not a luxury available in Attembris. The first time when he awakened and did not find himself inside a concrete world, but softly enfolded in a virtual, viscous fluid whose scent hinted of “mother” and “safety”, he had not wanted to subvocalize the command to dissolve the hammock; this time he woke and snapped right out of the dreamworld. Naked, Sajit dissolved the bedroom doorway with a half-uttered word and crept down the corridor to the breakfast circle. The storage bench was glowing.

He knelt next to it. A thought struck him: It’s the size of a coffin, a childsoldier’s coffin.

Because when the Inquestors came to cull the children, that was also the time when the coffins came home. Sajit wondered if there was some kind of servocorpse inside, perhaps one with a special synthesizing module; Arbát had hinted that such technology could be used to eke out the ensemble when an artist from the Clan of Shen performed solo in an Inquestral court.

Eagerly, he put his ear to the wood.

When his flesh touched the surface, the glow became brighter. Sajit tapped another rhythm, and heard the same rhythm echo back from within the wood. He put his lips to the bench and sang something he had just learned a few sleeps before, a song called The Space between Spaces….

I sing of the place

where stillness is rock

and where hardness is

the empty air;

I sing of the overcosm.

From inside came an answer:

I sing of the place

where light goes mad

and where songs have no endings.

“Who are you?” Sajit cried.

I am you. I am you. The melody arced and swayed with an overpowering sadness. It came from inside himself and outside himself at the same time. He found himself weeping.

Something was stirring in Sajit’s soul. There had always been an emptiness in that deepest place, but he had never realized quite how empty it had been. I have always been lonely, he thought. Those nights wandering in the forest — he had been looking for something. For someone who might say these very words: I am you. What could be inside this cold wooden box that could awaken such feelings? Sajit hugged the hardness, trying to infuse into it the warmth of his own nude body. He felt something huge and powerful seize hold of him, like the wind from a burning star; he trembled; he shook; he cried out. It seemed that the wood was responding … softening … that he was sinking into it. That could not be. It was a just a box, a wooden box.

But the box was dissolving, and his arms were closing around a human form. a gelatinous foam clung to it. His lips found other lips. His eyes gazed into another’s eyes. The foam was dissipating and he was pressed against someone whose body, cold at first, was catching fire from his body heat, starting to move, starting to return the embrace. The amnio oil that still clung to his limbs conjoined with the foam from the living thing within, as though the two fluids had the same genetic signature. Sajit gasped. He did not dare open his eyes. The creature from inside was thrusting against him, generating a warmth he had not felt except in dreams … the dreams he dared not speak of … loin to loin and lip to lip until without warning there came an explosion of feeling, much like singing a high note that is perfectly in tune, or playing a chord on the whisperlyre that resonates and resonates and resonates and never seems to leave the thick moist air.

Now lips at last broke free. At last bodies separated just enough for a puff air to pass between them. Sajit opened his eyes.

And saw himself.

Himself, as in a mirror. Slender hips, slender lips; slight, wiry, wide-eyed.

“I often dream of meeting myself,” Sajit said.

“And I have dream … of you,” the strange boy said, forming words slowly at first, but then with growing confidence. “I dream of you as I lie in the dark foam, in the land where only dream is real.”

Sajit sat straight up. “It wasn’t myself I dreamed of then. I think I dreamed about you, too,” he said, realizing it only for the first time.

“I hungry,” the other boy said. “No. Am hungry.”

Sajit realized know what the secret wooden box must have been. They had started up the doppling kit. A hair, a scab, an eyelash, a drop of blood is enough to get it going. His parents had been growing another Sajit.

“That was…”

“Surprising.” The other boy had finished the sentence.

“Why,” said Sajit, “you are me after all.”

“Yes I am you,” the other boy said. “I like what you do to me. When you put your arms around me and feels warm and cool at the same time. What is it?”

“I don’t really know.”

“I think I need food.”

“I’ll look.”

As Sajit rummaged in the seats, finding a pouch of instant zul and a few small peftifesht, he thought, So the Inquestors were coming after all.

“Something to eat,” Sajit said. He peeled the fruit and sprinkled the powdered zul over it. “What’s your name? I can’t very well call you by my own name.” Then he realized how stupid he must found. Dopplings have no names. They are created only to die. They stand in for the real human being. And yet in every sense of the world they too are human.

“You must name me,” the boy said.

Sajit looked into the boy’s eyes, his own eyes. In the village, Sajit did not really have friends. Even his family were remote. He had the night. He had the moons. He had the secret music of the lonely night. He had always wanted someone. Someone to whisper secrets to, someone to cling to in the darkness. He never dreamed that someone would be himself.

“Tijas,” he said.

His new friend smiled. “You name me after yourself,” he said.

And Tijas stepped out of the womb that had also been a coffin. He waved his hand over the wood and it became hard once more. “It keys to our genetic code,” Sajit says. “So you may command it as much as I may.”

“Teach me things,” said Tijas. “In the womb, I grow quickly. I not … connect … one thing with another.”

“The first thing we’ll teach you,” Sajit said, “is there’s more to life than just the present tense.”

“No time where I come from.”

And maybe, Sajit thought, there isn’t any time left for me, either.

The Inquestors were coming. No world was ever the same afterwards.

But, Sajit thought, I shall not be alone.

•••

Tijas was Sajit’s secret.

“You’re not concentrating!” said Arbát.

“And why should I concentrate?” Sajit shouted, and he began fingering the whisperlyre in a perfect sequence as he had been taught: dha, dha, bent dha, double-dha, sharp dha, sharper dha, dha-ni dha-ni ni-ni-ni, dha, dha. Not a note was out of place, every microtonal shrut was accurate to beyond the ear’s capacity to distinguish, and Sajit knew it. “I can already play it perfectly.”

“You can at that.” Arbát sighed. “And yet perfection is not an end in itself, but a beginning. Listen, you stupid boy.”

Sajit relaxed into the receptive pose called savezhatá, the locus of wisdom. His legs were crossed, sinking into the fur-cloaked floor. His palms were held out, cupped left and right, to receive the double stream of illumination that they said should come from the teacher, and the teacher’s teacher and the teacher’s teacher’s teacher, all the way back to Shen Élumel, the mother of songs. He knew that Arbát would play and the sequences would be indistinguishable from what he had produced, and yet he would be asked to hear the differences, and perhaps slapped around a bit if he could not come up with something, for what is the acquiring of knowledge without pain? So he entered the learning state, bracing himself a little in case his teacher was of a mind to strike him.

Dha, dha, bent dha —

But this time, it seemed to him that the notes touched him in a different way. The bending of the dha was the squeezing of teardrops. The nudge of the repeating ni ni ni, so close yet so far from the home key of sa, evoked in him such longing, a longing that was both dark and fiery.

Arbát’s voice was reedy and worn. And yet within that voice was fire, and also history. He was connected to the dawn of music. Now, above the ostinato of dha, dha, bent dha, he began to sing, his tones setting off the whisperlyre’s sympathetic strings and awakening the harmony globes within its mechanism. The words of the song were of love, of love between living stars, of the city built to memorialize the mutual suicide of twin stars that had once revolved around each other.

Unbidden, the image of Tijas surfaced. Tijas! Your eyes, my eyes! Your skin, my skin! Your touch, my touch! The confluence of sweat comingling with liquidescing amnio-wood, the eyes opening, the desire dredged up from an undiscovered darkness … Tijas! For a moment he was afraid he had spoken aloud. But no. He had stopped himself in time, and yet.…

Tijas, Tijas … the whisperlyre whispered, the name surfacing from the the sussurator at its heart. Invading the texture of the song, lacing each harmony with soft scintillant esses.

Abruptly, Arbát stopped singing.

The whisperlyre’s sound-colors became a jangle.

“A very good lesson for the day,” said the old teacher. Sajit flinched without thinking, knowing a blow would come, but instead it was a tender stroke of the neck. “Never subvocalize your innermost thoughts when you are in the vicinity of a whisperlyre that is being played. You know that the instrument has a very sensitive thinkhive attached to its sussurator. It’s there for a reason. The song is not just what you sing. It is what you are. And you have just revealed to me that you have a secret lover.”

“Not a lover!” Sajit protested.

But Arbát merely wagged a finger. “Love comes in many forms,” he said. “I told your parents they must not keep you locked away … somehow you would find a way out. You would meet people. After all, that is how you came to be here in the first place. Your parents have to understand that you will go where you will go.”

“Master, it isn’t like that.”

“Of course not,” Arbát said, “I am sure I have all the details wrong. I don’t know if this Tijas is a street urchin, or a kindly shopkeeper, or some mighty Lord or Lady you have run into in the corridors of your dwelling. But you feel what you have never felt before. Something that pulls from the deepest part of your unconscious mind.”

“Yes, master.”

“So what do you think of me now?”

“You’re not as boring as you used to be,” Sajit blurted out. Again, miraculously, no blow came. Indeed, his teacher smiled, something Sajit did not remember ever seeing before. His face was like the crinkled nets for catching phoslings in the double summer.

“I daresay,” Arbát said. “Now, learn your lessons carefully. When you perform, you are the song. When the song bleeds, you bleed. When the song weeps, you weep. You must distill the universal from yourself; yet how to do so when yourself is still but an embryo? I am not here to create your path for you, but to provide a bare minimum of light so you can see your own.”

Then came the blow, so stinging that Sajit clenched back tears. And yet, he thought, this pain is beautiful.

•••

That night, Chanika and Vimla quarreled, and the quarrel set off his parents. Sajit could hear them arguing into the night, and even when it all subsided, he could not sleep.

When he was sure no one would awaken (and when they quarreled, their sleep was usually deep) he dissolved the seal and pulled Tijas out of the storage box. The wood gave easily now, and hardened again when the boy was free of it.

“Come,” Sajit said, “we should get you some clothes.”

Sajit’s room was bare, though one wall had a built-in imager which he had set to show a vista of the forest beyond Attembris. Set in a temporal loop, on a slowed down cycle, the imager had a sense generator. A wind wafted and you could almost feel its touch. Tijas said, “I know this. I’ve been there.”

The moons were rising. In the distance — though the wall held no real distance — came the wail and clang of an itinerant klazmurah. The honeyed, cloying scent of vanjeris hung in the moist air — though the room itself had been environmentally regulated and was quite dry and of a perfect temperature.

“I shouldn’t be,” Tijas said, “but I’m cold.”

He was still naked from the doppling kit.

Sajit parted his amnio-hammock and pulled put a scrap of clingfire. He threw it to Tijas and it wrapped itself around his frail body. They sat at the edge of the amnio-hammock and watched the moons as they danced, and Sajit sang to his other self the song that he had learned that day, understanding it, perhaps, for the first time.

Tijas said, “I can’t go back into that box. It’s … a coffin. I won’t be alone anymore.”

Sajit said, “Stay with me then.”

“But people will find out.”

“Not right away,” Sajit said.

They leaned back against the amnio-hammock and it soon enveloped them both, and Sajit drew the darkness tight around them, enclosing them both. The warmth of the hammock radiated inward and they were safe as twins in a womb.

•••

In the morning, Sajit’s mother said, “You seem to be eating a lot!”

Sajit giggled as he bit into his third peftifesht, because Tijas was standing in a doorway and no one was looking that way, making faces. “I’ve got to go,” Sajit said and bolted to the hallway.

“What do you think you’re doing?”

“Come on, it’s my turn again.” Tijas grabbed his doppling’s half-eaten fruit.

Sajit hid to one side of the entrance and Tijas tiptoed to the breakfast circle. He squatted and went on eating.

“That was really fast,” said Chanika.

“More zúl?” said Ina, waving to the servocorpse. “It’ll get stuck in your throat.”

Tijas nodded and Sajit suppressed a giggle.

“Make him sing for it,” Chanika said.

“Yes! Sing!” Vimla said.

“Don’t be silly, Chani, Villi,” said their father, but Ina said, “Why not? You come back from the lessons and go straight to your room. We don’t know what you and wicked old Arbát are cooking up.”

“We don’t need to know,” said Sajit’s father. “It’s enough to know that because of Sajit, we have all this: a four-arjent income, a place in the capital in the shadow of the palace …”

“We were not nobodies in Attembris,” said Ina. “Sing for us, Sajit.”

Sajit froze. Tijas had never had a singing lesson in his life. They would all be in trouble.

But Tijas closed his eyes and took a deep breath and began, repeating note-perfectly what Sajit had sung to him last night. First the melismatic sequence with the slippery microtones: ha, dha, bent dha, double-dha, sharp dha, sharper dha, dha-ni dha-ni ni-ni-ni, dha, dha … then words, fitting to the serpentine melody as a shimmercloak bonds to an Inquestor’s skin:

do chitáry mu eyáh

mu eyáh élumy do

káng késy eklissío

kwan amby min eyáh?

I never sang those words to him, Sajit thought. Yet they bespoke his innermost feelings: “I have two hearts. I have two souls. How shall I pull them apart when both are I?” He looked at his parents, who sat ensorcelled by Tijas’s voice. How could it be that there was this other Sajit, conjured up from a wooden box? But there were other things Sajit realized as well.

His parents weren’t happy about their new situation.

On some level, they resented him. He had brought them untold fortune, and now they were losing control, becoming bystanders in a larger story.

Sajit gestured, trying to catch Tijas’ attention. On a high note, their eyes met, and Tijas’s voice cracked a little. His parents seemed almost relieved that their sound had shown a touch of imperfection.

As the song ended, and its final notes still hung in the air, it would take a while for his family members to awaken from the rêverie that great music always induces. With the instinct of a showman, Tijas slipped delicately away.

•••

Back in Sajit’s room, he said, “We fooled them!”

And Sajit laughed, but there was in his laugh a twinge of bitterness.

Before Tijas could ask him, Sajit said, “You know why.”

“Yes, I do.”

“We are each other.”

“Soon I’ll have to go back in the box.”

“Yes, as soon as they leave the house.”

“I don’t want to.”

“I know.”

Sajit kissed his doppling … himself.

Tijas said, “What are we doing?”

Sajit said, “I don’t know, but I know that we have each other, and we’ve never had anyone before.”

They kissed themselves again. Touched one another, fingertip to fingertip … and felt the warmth-in-coolness that came in no other relationship.

“Tomorrow morning,” Sajit said, “Let me go inside that box.”

Three

Inside The Box

Darkness. A deeper amniosis than any hammock. A warmth that tingled first, then seeped, then overwhelmed. Darkness that is mother, all-loving, all-embracing.

In the darkness, Sajit began to dream, and the dreams were not history, but they were history.

For a doppling kit must produce not a brainless entity with the same DNA as its double, but also a mind, a set of memories, a schooling about the nature of things. Alone in the amniotic world, Tijas had been in school, with prefabricated packets of information seeping into his brain in the semi-sleep of this artificial womb.

For twenty thousand years.…

A single world with a single sun. Many worlds with many suns. More worlds. More suns. A war between a million worlds. A ravaged galaxy. And then … a single world … a vast sphere that enclosed the great black hole the heart of the galaxy … on which a million suns shone … but where a klomets-high atmosphere scattered the light to a constant pearly radiance.

Fleeing her war, a lone woman comes to this world. The world, powered by a thinkhive so immense that its omniscience is indistinguishable from a deity’s … a thinkhive that has brooded for aeon upon aeon … a thinkhive that has never encountered a conscious being apart from itself … a thinkhive who is about to fall in love with the woman Vara.

A living world with all the knowledge in the galaxy … a woman … a love story … the first Inquestors … the harnessing of the deaths of suns to create tachyon bubbles … the creation of the delphinoid shipminds, the union of the giant brains that flew through the sunless sound with the crystalline eggs of the farfellor to make great ships that could sail the overcosm and hold the galaxy within the grasp of a few human beings … the freezing of history … the hunting of utopias … the whole story of the Dispersal of Man poured in through the synapse portals of the doppling kit. And Sajit learned more than he had ever done in the village schoolroom of Attembris, because the history he was learning now was the common or universal history, which is only taught to those who sail the spaces between spaces.

He learned of the decree that children should serve as childsoldiers, because only children have the quick reflexes to control the implanted laser-irises that can vaporize a pebble … or a city … depending on their focus.

He learned of the clans, brotherhoods that spanned the Dispersal, each with its own arcane rules, and how children could be named to a clan by an Inquestor … though usually only if they could survive the harsh winnowing of the childsoldier years. The clan that even his master, Arbát, had aspired to but never attained, the clan of Shen, the master Songmakers of the High Inquest. The Clan of Tash, the Rememberers; Rax, the Web Dancers; Kail, the Star Pilots.

… and how all wars between worlds had been ended through the grace of the Mother Vara and the power of the cosmic thinkhive of Uran s’Varek, the Inquestors’ homeworld…

… how wars between worlds had been replaced by the game of makrúgh, which sustained the balance of the Dispersal … how worlds could fall beyond and disappear from the

There was time, and no time.

***

In the time that was not time, Sajit stood in a circle of light. Around him voices were whispering:

History there is, and no history.

Just outside the circle of light, pitch-black. But here and there, a rustling sound and a brief glimmer of pink against blue … shimmercloaks.

The voices … always soft, always understated, yet behind the words, an unimaginable power, because the words were the Inquestral Highspeech … the language of poetry and song … the old tongue of the High Inquest, which normal mortals do not speak.

There is an old man’s voice. There is the voice of a boy. There’s a woman’s voice, a laugh that cascades like falling water.

The words are too soft to understand clearly, but once in a while there is a word that surfaces. Tekiánver … a tachyon bubble. Náruvas nîkas … new worlds. Abáchadand … the Falling Beyond.

He struggles to listen. He is eavesdropping on a game of makrúgh. The game is as mysterious as it is seductive.

There comes another voice now, breaking through the others; the clear voice of a boy no older than himself, he he speaks with the authority of one a thousand years old:

“Sing, boy, sing. Do not listen to our idle chatter.”

And a song springs to his lips:

Den om verék en-tinjet

In dárein shirenzheh

No man alive has touched

The silence between the stars.…

And he is thinking to himself: I wrote this. I, a child from a backworld, have written this song which the whole dispersal knows.

But not yet.

***

The box dissolved and Tijas was there again. And it was night, and the household was sleeping again. A view of the forest undulated against the wall as it sensed his wakefulness, and an artful perfume of night-blooms infused the room.

“How much time has passed?” he said.

“A day,” Tijas said. “And your parents … and your sisters … they never knew.”

“But isn’t it dangerous?”

“How dangerous? We are each other.”

“But …”

He looked into Tijas’s eyes … his own eyes. He sees so clearly, he thought. And I do too.

“Oh, Sajitteh … I’ve spent eternity inside the box … drinking in your youness with every slow breath.”

“But there are memories you don’t have. Things that were said to you. Places you went with them.” Tijas couldn’t know everything.

“Fortunate then that we’re such a loner.”

And Sajit saw that this was true. Only by having a friend had he discovered that he had no friends before. When he interacted with his family, they were doing, and he was observing. To be like Sajit to his family, Tijas had only to retreat into himself.

“Sajitteh … I went to your Master Arbát today! I learned so much! The scales, the melismas, the ornaments…”

“Did he realize?”

“How could he?’

“Did he hit you?”

“Yes, of course, of course. I can take the pain. I never used it feel pain before. It’s a new thing to me.”

“Don’t be too eager. Me, I’m never very eager. Arbát is a bore.” Sajit did not want to remember that Arbát, somehow, knew he had a secret friend. He did not to admit, either, how strange it felt that there was another Sajit sitting in his place, melting into savézhata, drinking in the old man’s knowledge. “The old man is a bore. We drift into another world when he speaks too much. The are universes beyond his universes. We have contempt for him sometimes.”

“But we never let that show, do we?”

Sajit laughed. “We try not to.”

“That mnemokitharon of his really stings,” said Tijas.

“You don’t know everything after all,” Sajit said. “There’s a way to neutralize the fine tuner. Then, when you play out of tune, make sure you yelp convincingly.”

“But that won’t help me learn to play.…”

“That’s what you think. The truth is, we are already better than old Arbát. Having to listen for your own mistakes will teach you to be better, more than any shocking mechanism.”

“But Arbát has all the scales and melismas in his head, like an encyclopaedia,” Tijas said “I can’t remember them all.”

“You already know them all. You just don’t know what they are called.”

“Do you think he has seen your soul?” Tijas said.

And Sajit said, “Quiet, quiet.”

***

It was Tijas who caught Arbát with the dreamstuff, and only because of his ignorance of a little thing. For though Tijas was wise in many ways, having sucked in knowledge straight from the memories of the microthinkhives embedded in the doppling kit, he was really only a few days old. Urna’s peculiarities of etiquette sometimes eluded him; sometimes he did not understand simple words, because the language module was not always updated to the latest shifts in dialect and slang. But he was learning every day.

This is what he told Sajit that night:

I come for Sajit’s lesson. But I’m early, and don’t know I should not enter until the summoning-crystal in the doorway shifted from blue to red.

And since the door-guardian was not one of the models that could think for itself, it simply let him in. It even bowed, though, being the cheapest of servocorpses, it did not speak. Sajit laughed as they snuggled in the simulated forest. And Tijas went on:

“Where is Arbát?” I say, and the dead man merely indicates with a slight incline of the neck. And then I see — oh, what I see! — it is madness!

Arbát was suspended in the air; below him was a pocket varigrav box, and next to it a fumigator; a golden ball of dreamstuff floated in the steam. Arbát clutched something —someone—in his arms; it seemed at first like a large, flopping doll, robed in torn skins. Floating in the gravity field, Arbát savagely clawing at the mannikin, the grinding, cursing at it.

I hide behind a potted gruyesh plant, with its flapping filigree of purple leaves.

“Ah!” Arbát was shrieking. “You beast, you monster, you arrogant child!” His eyes were open, but not gazing at the real world; it was some fantasy conjured by the dreamstuff’s vapors. He was thrashing about. He was partly naked; or rather, he wore a loose piece of clingfire that billowed about. His face was puffy, purple; he grunted, he groaned.

Then I see it: that Arbát’s mid-air frenzy it’s a kind of sick mockery of how me and my doppling cling to each other as we sleep in the warmth of the amnio-hammock.

Presently, Arbát seemed overcome by a kind of convulsion and began thrusting at the doll … it was, Tijas saw now, a servocorpse. Convulsing as well, in a timid echo of Arbát’s paroxysms. Arbát shuddering to some kind of climax and something flew off the corpse’s face and landed at Tijas’ feet … and he saw that the corpse had no face at all.

The face was blank.

And, staring up at Tijas from the twisted stem of the gruyesh plant … his own face, Sajit’s face.

Tijas froze. The dermomask was sheer and slippery, and it started to bond to the plant, sensing organic matter. And at that moment, Arbát tumbled to the floor! The servocorpse flew one way and Arbát scrambled to grab the mask … and saw Tijas … and pulled him into the chamber by the scruff … shaking and bellowing. “You! What did you see? How dare you enter?”

Tijas, terrified, began crying. And his teacher slapped him, over and over. Then stopped. Looked at his own hands in horror. “This will cost me everything. My livelihood. You uncivilized creature, didn’t your parents teach you what a summoning crystal is for?”

Arbát began to weep. And his grief was more frightening than his anger. And though Tijas was sore from being slapped repeatedly — Arbát was not a small man — he could not help feel a kind of pity.

“I saw nothing, Arbát,” Tijas said. “I’ve only been here for a moment or two. For my lesson.”

And the wonder of it was that Tijas no longer felt he had to call the master master, or address him by any honorific; what he had seen, though he did not really understand it, had diminished the grand musician.

“Sajitteh,” Arbát said. “There are … things … you’ll understand when you are older.”

“Yes.”

“No lesson today.”

Tijas rose, thinking he should leave. Then he saw the servocorpse lying on its side in a corner of the room. It had, indeed, no face, and its body, too, was featureless. Though naked, it did not even have a gender. But its back was scarred with scratches and gouges. A servocorpse feels no pain; the centers for all human feelings are turned off when it is turned on.

A cheap toy, brought to life by imagination fueled by the fumes of dreamstuff.

“No lesson today, but …” Arbát gathered the scraps of clingfire, strung them together to cover himself more completely. “But I will take you for some … some chocolate.”

Tijas followed Arbát out to the street.

***

The displacement plate was right at the door, so that one could go from this corridor to the next destination simply by subvocalizing a few coordinates, but Arbát sidestepped the plate; taking Tijas by the hand, he walked him down a stairwell and out through an alley.

Arbát said, “You do not always find the thing you want, Sajitteh, when you take the displacement plates.” His gnarled hand held the boy’s firmly. His manic actions seemed forgotten. They turned a few more corners and the smell of chocolate hung heavy in the air. There were stalls everywhere. Here a whirring contraption spun chocolate from powder into cobweb patterns; here a woman with three eyes was melting chocolate with a flametorch and drizzling it into pincushions of snow. Here a fondue with intoxicating dreamberries, the source of dreamstuff.

Arbát stopped in front of a one stall, seemingly at random; the minder was a grinning, fat man with no hair. Two tripods rose for them to sit. Arbát ordered, a mushy brown paste sprinkled with dreamflakes, and for Tijas an icy, crunchy bowl of confections shaped like pteratygers.

Tijas bit off a wing. The liquid inside was sweet, but it had a pungent aftertaste. He waited. It was clear that Arbát wanted to say something. At last, his tongue loosened a little more by the flakes of dreamstuff, he said, “It’s worse for me than for you, you talented little shit. You have a family of sorts, even though your friends are back in the village; chances are they were never really your friends anyway. Everyone I ever had is dead.”

“Dead?”

“Mine was a world that fell beyond,” Arbát said. “Before I came here. They chose me so the music of my world would not die.”

“… and it hasn’t.”

“No, it hasn’t. But I did.”

“I see,” said Tijas, though he really did not.

“I wish I could wring your scrawny neck, sometimes. I know there’s someone you love. I only have the words, the melismas, not the truth of love. Can you blame me for wanting to—”

“I don’t know what it is you want, Master Arbát,” Tijas said.

“They are pleasure corpses,” Arbát said. Tijas supposed it was by way of explanation. “You can print out the faces on any thinkhive, any faces you want; they’re cheap, these corpses, poor quality; perhaps they died in accidents, were disfigured, were diseased; so the servocorpse factory just grinds them to a blandness. Completely featureless. And then they can be anyone you want to love. Or hurt. But Sajitteh … I would never hurt you too deeply. You are the thing I can never be, you see. I must love you for that.”

Tijas said the one thing he knew Arbát wanted to hear. “You will never hear me speak of any of this, master. Not ever.”

“And because you can hold it all inside yourself, you shall be Shen. Which I never became.”

“When I attain it—I shall insist they make you one!”

And Arbát laughed bitterly. “When … a stripling who’s never burst the milkpod says ‘when, when’ … knowing his destiny already.…” And called for a posset of crushed violets, perhaps to steady his emotions. “Airos hokh’tásieh; ektáshila shiklát,” he added in the highspeech.

“Love is the great joy; the lesser joy is chocolate,” Tijas said.

“Well learned!”

***

And that’s how I learn that our teacher is addicted to dreamstuff, and that he has some kind of obsession with us, and that he acts out his obsession on a helpless little pleasure corpse …

“You have all the fun!” Sajit said, trying to reconcile this astonishing story with the Arbát he was used to. “Why couldn’t this happen when I was with the master?”

“He ever bruise you this badly?”

“He ever buy me chocolate?”

“But seriously,” Tijas said, “something has changed.”

“We have power now.”

“Sajitteh, what’s bursting the milkpod?”

“I don’t know. I’ve heard that we’re too young to understand.”

“I’m going to ask mother and father, at breakfast.”

“Who says you’re the one having breakfast tomorrow?”

“I do, brother. Be quiet, now.”

“Yes. They’ll wake.”

***

So, when he fingers blundered at the mnemo-kitharon, Sajit declared that he wanted chocolate.

“Oh, you manipulator,” Arbát muttered, “you shrewd little pteratyger cub.”

But Arbát took him to the alley. And left him on the tripod, in front of the vendor, while he wandered off by himself. And in that moment Tijas slipped out of a side street. Too many people thronged about for anyone to notice them, shadowslim, flitting in and out; sensing each other’s thoughts, they could switch in an instant, catching just the moment when no one was looking.

Tijas said to Arbát, “So what, Master Arbát, is bursting the milkpod? I have no one to ask.”

“Try your parents,” Arbát said.

A few minutes later, Sajit said, “So, Master Arbát, what exactly does bursting the milkpod mean? Is it the highspeech?”

“Little beast! Did I not tell you to ask your parents?”

“Did you?”

“Not five jipek ago. Either you are exceptionally forgetful for one so young, or there are two of you.”

‘Oh, you are a comedian, Master Arbát.”

Thus it was that Arbát became no longer a martinet taskmaster, but a fellow traveller. A friend, even. And it was all because Tijas had walked through a door uninvited.

***

Mind you, he did not stop thrashing the boy, or boys, rather. They accepted that; it was tradition. But often it was a perfunctory slap and a soft-pedaled tongue-lashing.

It was because of the occasional slap that the boys learned something new about each other.

Sajit had let Tijas go to the lesson one morning, because he wanted to sneak out to the palace bestiary. But he had not gone five steps across the square when he felt a sharp pain rip across his knuckles. He felt his left hand with his right, expecting a welt or abrasion, but there was nothing. He looked down and saw a red stripe, quickly fading. We’re more linked than I thought, Sajit reflected. He needed to reach his doppling right away, to share this news. And so he run to the other side of the square and whispered the coordinates, barely noticing the displacements he passed, the Fountain of Unwept Tears, the Forest of Statues, the Street of the Servocorpse Factories … he reached the entrance to the apartment and lurked in the hall, which was decorated with busts of the nobility, set on columns of azurite, their eyes sculpted from blue diamants. Eventually, he knew, they would emerge … the chocolate ritual had become a regular thing. When they did, he motioned Tijas, who shouted, “I’ll be there in a moment, Master, do not wait,” and then he embraced Sajit, laughing.

“Oh, it’s so risky, you, me, here, in the corridor — you never know which of the statues is a spy.”

“All right,” Sajit said, “Close your eyes.”

Tijas said, “Why did you slap me?”

“I didn’t. I slapped myself.”

Tijas said, “You’re right. This was worth the risk, coming here like this.”

“We can play this game almost openly,” Sajit said. “We don’t have to pretend to be each other.”

“Slap yourself again! I want to feel it again.”

***

At the chocolate stand, Arbát’s absences became a ritual. And they became longer and longer, and when he returned, he was more distracted each time.

So the boys began following him.

Sometimes it was buying dreamstuff. For three gipfers you could buy quite a handful. But once, it was something else. It was hard to follow someone moving swiftly through the city via displacement plates; you had to leap on just so, in the split second when the the thinkhive reset itself for the next passenger, and make your mind blank so you didn’t not accidentally subvocalize a completely different command; and you had to avoid being noticed by the one you were following. It was only because Arbát moved so sluggishly, never looking around, that he was easy ti follow.

This time his destination was, ironically, the palace bestiary, it seemed. It was a public day, a crowded day, and the pteratygers were being fed. Arbát moved slowly, but he was purposeful; the boys would have liked to watch the feeding. The keepers released a flurry of firephoenixes into the air, and the pteratygers swooped and hovered, avoiding the flames in time to snatch the birds as the dived earthward, and all safely inside a sphere of force. The crowd gasping at every somersault that ended in a fiery kill. The boys tried not to stop and look to long.

“He’s turned a corner,” Sajit said. Arbát had slipped between two serpentine columns. The boys followed. Kept to the shadows. Which was wise, because they had stumbled into a royal council chamber, and seated on a hoverthrone was the very man Sajit had met, once, in a forest, in the village of Attembris, beneath the dancing moons, the moons that had seemed to sing.