This is a very hard thing to write. One of the original members of my Free University SF Class (see older columns), which grew into PESFA, and sponsored MosCon, has left us for higher realms. Beth Toerne, one of the staunchest and most integral members of the SF group I led in Pullman, WA/Moscow, ID, back in the 1970s and 1980s, has been claimed by cancer. She will be sorely missed, not only by her husband, Fred Toerne, and her son, John Finkbiner, but by everyone whose lives she touched. Figure 1 shows Beth, carrying John (as a “baby bump,” dancing at an early convention, probably a MosCon. She danced a lot.

Figure 2 shows Beth sometime in the last year; she was always laughing, and alive, and enthusiastic. Born only a few years after I was (she was born in 1950), she always threw herself into any project she undertook with great enthusiasm; she served MosCon in many ways—probably as chair once, though I don’t have all the records with me—and made the lenses for the E.E. Smith “Lensman” Award that was given at MosCon to a professional writer and artist in our field. (The award was designed by Jack Gaughan, but Beth designed and made each of the lenses.) She had, at various times, a bookkeeping service, a craft store, and probably many other projects after I left Pullman for Canada in 1985. I’m still gobsmacked by this; I can see and hear her in my mind’s eye, laughing and dancing. Farewell, Beth! You were lovely and loved by all!*

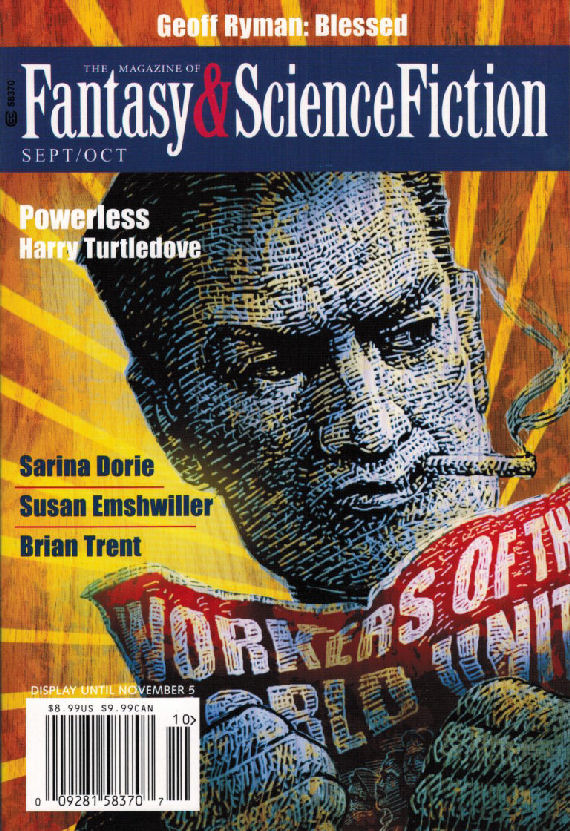

For this week’s review, I am pleased to bring you what I consider to be a very strong issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction! The cover is by Michael Garland, illustrating the story “Powerless,” by Harry Turtledove. As with many of Turtledove’s works, the story deals with an alternate universe United States, more akin to Soviet Russia in the 1940s and 1950s, than the U.S.—or maybe it’s a cautionary tale about what the U.S. might become. It’s a cross between 1984 and, I dunno, The Man in the High Castle. But rather than a dreary, Communist Britain, or a U.S. divided by conquerors, our hero Charlie Simpkins lives in Southern California—West Coast People’s Democratic Republic. In the San Fernando Valley, to be exact. But it’s a Southern California that would be instantly recognizable to anyone who lived through the Berlin partition (on the East side), where you have to toe the Party line and spout the Party line, and post the Party posters.

Not that there’s only one Party, mind you, but the others, including Democrats and Republicans, are parties you don’t want to be caught voting for, unless you want to lose your job, your crappy little one-bedroom apartment (that you, your wife and your two kids live in), get sent to a labour camp, or another of the punishments awaiting dissidents and subversives. How Charlie gets in trouble and possibly—just possibly—gets a ray of hope in his drab existence, comes to you courtesy of Vaclav Havel’s essay on totalitarianism/bureaucracy and resistance, via Turtledove. Like I said, maybe it’s a cautionary tale, too. Well written, but then, what else did you expect from Turtledove?

The rest of the fiction will be dealt with in page order.

Possibly because I’ve recently reread Stephen King’s The Gunslinger, and have been watching the “Saint of Killers” on Preacher, the story “Shooting Iron” by Cassandra Khaw and Jonathan L. Howard struck a chord. Jenny Lim is a twenty-three-year-old Asian cowgirl. She’s ostensibly visiting Britain for a Wild West convention in Bristol, and has brought her gunbelt (no gun) and Stetson with her, so she can rent a gun (with blanks) and enter the “fast draw” competition.

Only it’s a complete lie. She came in under the name of “Tan,” and she has no intention of going to a Wild West con; she’s here to kill someone—several someones, if her luck holds out. And she didn’t need to bring a gun; when she needs it, the gun will be there. Oh, yeah—and she’s actually dead. This story’s like Supernatural meets Preacher; it’s vicious and violent and I absolutely loved it.

Brian Trent’s “The Memory Box Vultures” is kind of a possible near-future. As we all know now, data tends to “live forever” on the internet. Well, what if all that data, combined with AI, kept a person alive, virtually, in the future. Accessible through your VR implants, visible only to you (and anyone else it was interfacing with at the time), linked to a gravestone, a physical location, a website, etc. How would that play out? What if everything you saw and heard was archived somewhere in the Cloud? With VR and AI, a form of you could be around virtually forever. Would erasing your backups be the same as murdering you? Lots of questions here, and a few answers.

“The Men Who Come from Flowers” by Bonnie Jo Stufflebeam is an odd one. Until I was most of the way through it I didn’t realize it had a feminist slant; a well-written story like this might cause a few assumptions to crumble. I won’t attempt to describe it; read the title as absolute truth if you must know what it’s about.

Jeff Crandall’s “What Loves You” is a short, but very punchy poem. If what you wish for comes true, is it good for you—or for what you wished for? It reminds me of a very old Mad Magazine story (back when it was a comic) by Will Elder, called “Heap.” Make of that what you will. Like everything else in this issue, well written.

“The Gallian Revolt as Seen from the Sama-Sama Laundrobath” by Brenda Kalt is very much in the vein of old-style SF; we have residents of a planet who are just ordinary people trying to get by in the middle of a conflict. It’s told from the viewpoint of a somewhat older woman, who illicitly uses her connection to a “laundrobath” (laundromat and bath) to make a little extra on the side; whether she unwittingly helps one side or another isn’t the point. Told with the kind of detail of culture, mores and all that writers like Andre Norton used to put into their stories—and don’t you miss that? I sure do. Excellent story, well written.

“We Mete Justice with Beak and Talon” by Jeremiah Tolbert takes a news item—that in Europe and/or Asia they’re using birds of prey to deliberately take down illegal drones—and carries it into the future. What if the birds, who are allied mentally with their human controllers—actually glory in the pursuit and destruction of such drones? Told from a bird’s point of view.

Yukimi Ogawa’s “Taste of Opal” is a very complex story set in a sort of feudalistic Japan (though this is more implied than overt). It concerns people who are actually the origins of semiprecious stones like opal and jet. The protagonist, Kei, is an Opal-conc; she is sold by her parents to jewel merchants who then farm her out to jewelers for her blood. Once her blood is drawn, it turns into an opal, apparently (the exact process is not detailed, or I missed it). How Kei is handled and how she gets the upper hand over the merchants; how they become dedicated to her welfare, form the crux of the story. This sounds trite—especially considering the subject—but this is a jewel of a story!

“Suicide Watch” by Susan Emshwiller marks the return of an Emshwiller to the pages of an SF magazine after far too long. Daughter of writer Carol Emshwiller and artist/filmmaker Ed Emshwiller (and, I assume, sister to Stoney Emshwiller), she has been making a living as a screenwriter. The Emshwillers have given so much to SF that it’s an absolute pleasure to see one return to our genre. In a near-future world where people will do almost anything to feel something, the most popular way is the suicide watch. You pay your money and when someone’s ready to kill themselves, you get notified. You alone—if you’ve got the money—can not only watch, but can record (for your own pleasure or for uploading to social media) the death. Gee, can there be a downside to something this pleasant? <Sarcasm font> Great and nasty little story. I look forward to more Emshwiller in future!

Gregor Hartmann’s “Emissaries from the Skirts of Heaven” is about Grace, who lives in a future where religion holds sway and people routinely travel between—and fight between—planets. “Emissaries” details Grace’s journey from small child, being taught by her smart slate to read (“glyphs”), through childhood, to adulthood to, finally, teacher. An awful lot to pack into a single short story, but Hartmann does it beautifully. And as an a-religious person myself, I didn’t even grinch at a religious future (even if it’s not mine).

“Impossible Male Pregnancy: Click to Read Full Story” by Sarina Dorie is a cross between online clickbait and a National Enquirer type magazine (online, naturally). What happens if a man gets pregnant? Does he instantly become the most famous man in the world? But what if this is a somewhat common—if not common, at least not unprecedented—occurrence? Dorie gives us scientific reasons for male pregnancy (well… somewhat believable reasons, anyway); and what can happen if men do get pregnant. She deals with loss of masculinity (in the eyes of a man’s male compatriots), hormone imbalance (I kept visualizing Duane Johnson in Jumanji looking up at the sky and repeating to himself, “Don’t cry. Don’t cry. Don’t cry.”), and what can happen if it’s not a real pregnancy or an hysterical pregnancy. Cleverly told with a certain amount of humour but also a certain amount of gravity.

And last—but as they say, not least—“Blessed” by Geoff Ryman takes us to a place called Abeokuta, seventy miles from Lagos, Nigeria. According to the story notes, Ryman is a frequent visitor to Nigeria, where he’s an administrator for the Nommo Awards, which annually recognize the best in African speculative fiction. The story is set in a local tourist attraction, a rock called Olumo. Abeokuta means “beneath the rock,” because that’s where the heroes hid, according to the story’s unnamed protagonist.

She is an educated white South African, and keenly feels the sting of what happened in Africa under the Boers, and does her best—though not the best at reading social cues—to set both her hosts (the tourist guides) and the other tourists, all of whom are black, at ease, though she’s very awkward due to embarrassment because of white/black/colonial history and does a terrible job of it.

Not to worry, Mother Africa, it seems, has a way of changing everything. (I can call her that, because after all, we are all Africans if you go back far enough.) The protagonist goes on a strange journey, and much will change for her before the journey ends. Ryman, I think, has a feel for Africa. Well done.

So—you want to know how I feel about this issue? I think it was a very good issue; in some ways exceptional, and I have no problem assigning it four flibbets. ¤¤¤¤!

*As Cassidy the loveable, wastrel, Irish vampire said on the TV series Preacher (paraphrased here): “One of the worst things about living forever is that you eventually get to see everyone you ever loved die.” Unfortunately, that holds true for a long life, too.

Comments? Go ahead and comment here or on Facebook. Your comments are welcome, pro or con! (I usually learn something from negative views or disagreements!) My opinion is, as always, my own, and doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of Amazing Stories or its owner, editor, publisher or other columnists. See you next time!

I don’t see the year on this cover–was it indeed for F&SF Sept/Oct 2018?

“Vaclav Havel’s essay on totalitarianism/bureaucracy and resistance”: that would be https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Power_of_the_Powerless ?

Yes, Graham, it’s for the current (2018) F&SF. All you have to do is look at their website for confirmation (https://www.sfsite.com/fsf/).

And yes, the author cites that article in the intro to the story. I should have been clearer in my review.