A man, clad in some sort of protective suit, fires a gun. Nearby are various short, green humanoids, along with a larger, red-skinned being. But these are not his targets: he is aiming the gun at a weird mass of multi-coloured light that hovers in front of him. It was June 1927, and Amazing Stories was appealing to readers with imagery that could just as easily have appeared on its older, stranger rival Weird Tales.

A man, clad in some sort of protective suit, fires a gun. Nearby are various short, green humanoids, along with a larger, red-skinned being. But these are not his targets: he is aiming the gun at a weird mass of multi-coloured light that hovers in front of him. It was June 1927, and Amazing Stories was appealing to readers with imagery that could just as easily have appeared on its older, stranger rival Weird Tales.

But the issue opens with a discussion of a different cover. Back in December 1926, Amazing featured a cover image with no relation to any stories inside, and challenged readers to write their own works of fiction inspired by the illustration for a chance to win a cash prize. In this latest issue, Hugo Gernsback announces that he and his associates have chosen the three contest winners from around 360 entrants. These prize-winning tales – all using the cover elements of a flying spherical craft, a levitating ocean liner and a race of red-skinned humanoids with fin-like appendages – are the main attractions of this issue, with four runners-up slated to be published at a later date

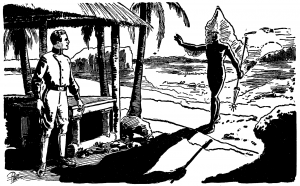

“The Visitation” by Cyril G. Wates

Kicking off the issue is the story that won the first prize of $250.

Kicking off the issue is the story that won the first prize of $250.

In 1949, a steamer happens across an unknown land while en route to South America. The crew disembark to explore, and they find a striking landscape with black cliffs, green grass, and a pool of water shimmering with the colours of the rainbow.

Next, a strange spherical vessel descends from the skies to meet them. When the inhabitants emerge, the explorers initially take them to be Native Americans, complete with headdresses; but they are in fact a race of humanoids with elaborate fins over their heads. Learning English through some form of telepathy, these beings introduce themselves as the Deelathon. They reveal that they cannot venture into the wider world because their flying machines function only when above a black rock that runs below their country, while surrounding sea and cliffs prevent travel by foot.

The Deelathon also express sorrow when they realise that the newcomers lack a trait that they call Thon. It turns out that Thon is a force of life (which the story equates with the cosmic rays studied by Robert Andrews Millikan) that allows longevity and telepathy. Thanks to the Thon, the Deelathon live a peaceful, healthy existence which is contrasted with the barbaric ways of Earth (the story makes satirical digs at war, fashion and marriage ceremonies).

A hundred Deelathon accompany the sailors on their voyage back; the explorers, seeking to hide the existence of the Deelathon’s homeland, pass the strange beings off as aliens who arrived on a meteorite. The Deelathon end up dying as a result of being “unfitted physically to cope with the misery and disease and death” found in the benighted world outside their home, but their passing was not in vain, however. They successfully taught the ways of the Thon to their hosts. and were able to turn Earth into a Utopia. The framing device of the story is set in the twenty-first century, where humanity enjoys a life without old age, warfare, or racial divisions, and honours the memory of the Deelathon who brought this state of affairs about.

The debut story of Cyril G. Wates, who would turn up in a few subsequent issues of Amazing, “The Visitation” has strong similarities to A. Hyatt Verrill’s “Beyond the Pole”, albeit with a dash of utopianism not found in that work.

“The Electronic Wall” by George R. Fox

The image of the levitating ocean liner, which plays a small role in Wates’s story, provides the central premise of the second-place winner: George R. Fox’s “The Electronic Wall”.

The image of the levitating ocean liner, which plays a small role in Wates’s story, provides the central premise of the second-place winner: George R. Fox’s “The Electronic Wall”.

This story begins in 2038, with the solution to a hundred-year-old mystery and the creation of another puzzle. In 1938 (during World War II, according to the story’s future history) a US naval ship called the Woodrow Wilson vanished without a trace. A century down the line, it was discovered – in the Victoria desert, with no sign of ever having been inhabited. How did it get there?

The narrator, Randall Prindle, reveals that he alone knows the answer as he was a member of the ship’s crew. In a flashback to 1938, he and the other crewmen notice strange gravitational phenomena on board the ship. An object thrown overboard comes back in the manner of a boomerang. A sentry fires a gun into the air, and the bullet ends up in the leg of a man on the deck. Weirdest of all, the men find that they can walk down the side of the ship and end up on the bottom, standing upside-down with no sea in sight.

The people of the 1930s possess a primitive telepathy, and using this ability the crew pick up the voice of a mysterious speaker. This unknown individual assures them that they are being taken on a journey for benevolent purposes. Heading out to the deck, the crew see the tiny shape of Earth so far away that it is only identified through a telescope. Above the ship is a spherical vessel; previously hidden by fog, this craft had been responsible for carrying them all the time. The globe maintains an electronic wall (something that, today, would be termed a force field) around the Woodrow Wilson, preserving its oxygen and causing the gravitational anomalies.

The telepathic voice reveals that it hails from an ancient race older than mankind. This species has passed through “savagery, barbarism, slavery, serfdom, capitalism, socialism, into a pure freedom wherein the one purpose and delight is to know the truth and to serve.” The spherical craft – named Paulo – travels from world to world, absorbing energy to power the inventions of its inhabitants.

But this still leaves the question of where the aliens are taking the ship. It turns out that the beings are Martians, and that the male of their species is dying out. Consequently, the women of Mars have decided to abduct a healthy amount of men from Earth so as to ensure a future generation. Upon seeing the beautiful Martian women (whose white growths are described as angelic feathers, rather than the fins of Wates’s story) the entire crew of the Woodrow Wilson consents to the arrangement, sparing little or no thought for any loved ones back home; Randall acknowledges that hypnosis may have played a part here.

Indeed, Randall loves his new home so much that he is planning to go back there, and stopped off on Earth only briefly to impart a message. The story ends with the protagonist imploring his readers to use telepathy to avert a third world war:

Will you who love the right join me day by day in sending out the thoughts? Christian, pagan, Jew, or Mohammedan; Brahman or Buddhist; black or red; white or yellow; of whatever race or creed, color or nationality, if you would have peace hold the world, heed my call.

“The Fate of the Poseidonia” by Clare Winger Harris

Finally, we come to the last of the prize-winning stories; its author, Clare Wigner Harris, is recognised as the first woman to write for science fiction magazines under her real name. “That the third prize winner should prove to be a woman was one of the surprises of the contest”, remarks the editorial introduction; “as a rule, women do not make good scientifiction writers, because their education and general tendencies on scientific matters are usually limited”. However, the magazine reassures its readers that Harris’ story is “the exception [that] proves the rule”.

Finally, we come to the last of the prize-winning stories; its author, Clare Wigner Harris, is recognised as the first woman to write for science fiction magazines under her real name. “That the third prize winner should prove to be a woman was one of the surprises of the contest”, remarks the editorial introduction; “as a rule, women do not make good scientifiction writers, because their education and general tendencies on scientific matters are usually limited”. However, the magazine reassures its readers that Harris’ story is “the exception [that] proves the rule”.

The story begins with astronomer George Gregory being introduced by his professor to an odd-looking man named Martell, who has an interest in Mars – specifically, the amount of water that may exist on its surface. Later, Gregory catches sight of Martell speaking in an unknown language to a mechanical device with a vapour hovering above. “Good heavens!” thinks the protagonist; “Was this a new-fangled radio that communicated with the spirit-world?” Gregory also finds that Margaret, the object of his romantic attentions, is taking an inconvenient interest in this newcomer.

Meanwhile, strange things are happening in the world. The Pacific Ocean suddenly recedes by several feet, and an aeroplane mysteriously goes missing, a surviving crew member telling a bizarre tale of the plane shooting upwards with no apparent cause.

Amid these strange goings-on, Martell falls ill. Gregory lets his suspicion get the better of him and plays with Martell’s machine behind his back; out of its vapour, an image appears. It shows a man with reddish skin, and some sort of elaborate headdress. Gregory concludes that this individual is a Native American chief, and also notes a remarkable resemblance to Martell. Adjusting the device he obtains another image, again showing a Martell lookalike, this time with a German newspaper.

“I was madly desirous of investigating all the possibilities of this new kind of television set”, he narrates. “I had no doubt that I was on the track of a nefarious organization of spies, and I worked on in the self-termed capacity of a Sherlock Holmes.”

Finally, he conjures an image of an alien landscape and its inhabitants, revealing Martell’s secret Martell is a member of a race of red-skinned, white-feathered Martians, who travel in spherical craft. They were responsible for stealing Earth’s water to refill their drying canals, and stole the missing aeroplane as a trophy.

Gregory tries to warn the authorities, only to end up in an asylum. Then news hits that a ship, the Poseidonia, has gone missing as did the aeroplane, and Gregory persuades the sceptics to activate Martell’s machine. The device broadcasts a message from Margaret, who turns out to have been on board the ship; she states that the Martians have all the water they need and will leave Earth alone, while she is content to stay on her adopted planet. Gregory’s planet is saved, but he has forever lost his love.

With her tale of a dying Mars and its hostile inhabitants, Clare Winger Harris departs from the utopianism shown by the other two prize-winners.

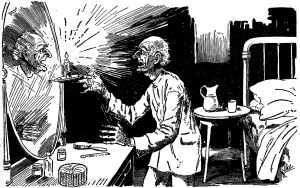

“The History of the Late Mr. Elvesham” by H. G. Wells

The prize-winners do not take up the whole of the issue, which features a number of other tales – including another reprinted story by the ever-reliable H. G. Wells.

The prize-winners do not take up the whole of the issue, which features a number of other tales – including another reprinted story by the ever-reliable H. G. Wells.

The protagonist, Eden, meets a strange old man who turns out to be the noted philosopher named Egbert Elvesham. The philosopher has been looking for an heir to inherit his wealth, and he chooses Eden for this role.

During one of their meetings Elvesham gives Eden a drug, which he ingests. On the way home, Eden sees the locations around him seemingly transform from one place to another, and recalls memories of events that he never experienced; his own memory, meanwhile, starts to leave him.

Waking up in the night, Eden finds himself in an unfamiliar bedroom; he then looks in the mirror and sees the face of Elvesham. This was the nature of the inheritance: Eden inherited Elvesham’s body, while Elvesham was granted the youthful frame of Eden. The story ends with Eden-in-Elvesham committing suicide, while an epilogue reveals that Elvesham-in-Eden had been hit by a car shortly beforehand, scuppering his plan for an extended life.

The body swap has become one of the hoariest clichés in fantasy, but Wells’ 1896 treatment of the theme still carries a charge. The editorial introduction speculates that the story may have inspired G. McLeod Winsor’s Station X.

“The Lost Comet” by Ronald M. Sherin

Mathematical genius Professor Montesquieux investigates the fate of a comet discovered in the nineteenth century, which once became visible from Earth on a regular basis but later dwindled to a tiny fragment. Astronomers deduced that the comet disintegrated, but using a process that he terms “cometary geometry”, the professor deduces that the principal part of the comet is still out there, and will strike the Earth in six months’ time.

Mathematical genius Professor Montesquieux investigates the fate of a comet discovered in the nineteenth century, which once became visible from Earth on a regular basis but later dwindled to a tiny fragment. Astronomers deduced that the comet disintegrated, but using a process that he terms “cometary geometry”, the professor deduces that the principal part of the comet is still out there, and will strike the Earth in six months’ time.

However, he has trouble alerting the world to this impending apocalypse, and he is dismissed as a crank by the astronomical community. The professor has “evolved a new and revolutionary system from the realm of pure mathematics” as a result of having “scorned the applied mathematics of his time”, and is consequently unable to make his calculations public.

But the professor’s detractors are forced to eat their words when a light appears in the night sky. The world braces itself for its impending destruction… only for the comet to narrowly miss. It turns out that the professor failed to take into account the effect of Jupiter’s gravitational pull upon the comet. The story ends on an ironic note: while Professor Montesquieux is redeemed in the eyes of his peers, he comes to see himself as a failure due to his miscalculation.

“Solander’s Radio Tomb” by Ellis Parker Butler

After ending a heated argument with an acquaintance about the relative merits of tube and crystal radio, a lawyer bumps into a wealthy local named Remington Solander. This elderly millionaire recognises the lawyer as chairman of the trustees of a nearby cemetery, and asks him for help in drawing up a will.

After ending a heated argument with an acquaintance about the relative merits of tube and crystal radio, a lawyer bumps into a wealthy local named Remington Solander. This elderly millionaire recognises the lawyer as chairman of the trustees of a nearby cemetery, and asks him for help in drawing up a will.

Solander, it transpires, has a keen interest in radio and resents the typical ways in which it is put to use (“Jazz! Cheap songs! Worldly words and music!”). He has already stipulated in his will that a million dollars of his wealth by used to set up a broadcasting station dedicated to hymns, sermons and other such pious material; now, he arranges for the cemetery to host an extension of this idea. He requests that, after he dies, he be interned in a prominent and well-cared-for granite tomb, with a built-in loudspeaker and radio tuned into his station.

Solander duly passes on, and the cemetery carries out his final wishes. The radio tomb, blaring out sermons, becomes a local landmark. But everything goes awry when the government passes new regulations on radio, and assigns new wavelengths to stations across the country. This causes the tomb to begin playing a different station – and, as Solander’s will stipulates a specific wavelength rather than a station, the cemetery is powerless to alter this:

[T]he next day poor old Remington Solander’s tomb poured forth “Yes, We Ain’t Got No Bananas” and the “Hot Dog” jazz and “If You Don’t See Mama Every Night, You Can’t See Mama At All,” and Hink Tubbs in his funny stories, like “Wel, one day an Irishman and a Swede were walking down Broadway and they see a flapper coming towards them. And she had on one of them short skirts they was wearing, see? So Mike he says ‘Gee be jabbers, Ole, I see a peach.’ So the Swede he says lookin’ at the silk stockings, ‘Mebby you ban see a peach, Mike, buy I ban see one mighty nice pair.’ Well, the other day I went to see my mother-in-law—“

You know the sort of program.

An amusing example of the inventions-gone-wrong stories often printed in Amazing, and a vivid snapshot of radio culture circa 1927.

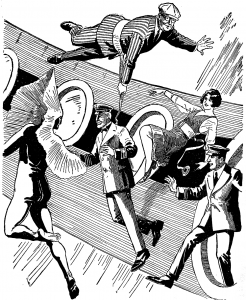

“The Four-Dimensional Roller-Press” by Bob Olsen

Youthful genius William James Sidelburg has invented a device for compressing or expanding an object as it extends into the fourth dimension. Just as a pile of circles becomes a cylinder, Sidelburg has assembled a set of spheres to form a four-dimensional roller, which the protagonist (an acquaintance of Sidelburg’s) describes as resembling a bunch of grapes or a blackberry. The spheres surround what appears to be empty space, but is in fact occupied by fourth-dimensional mass: when the main character tries to place his hand into the gap, he is blocked by something hard and invisible.

Youthful genius William James Sidelburg has invented a device for compressing or expanding an object as it extends into the fourth dimension. Just as a pile of circles becomes a cylinder, Sidelburg has assembled a set of spheres to form a four-dimensional roller, which the protagonist (an acquaintance of Sidelburg’s) describes as resembling a bunch of grapes or a blackberry. The spheres surround what appears to be empty space, but is in fact occupied by fourth-dimensional mass: when the main character tries to place his hand into the gap, he is blocked by something hard and invisible.

Putting his invention to the test, Sidelburg runs a steel cylinder through the mechanised spheres. It comes out larger but unnaturally light, having doubled in volume and reduced in density. After going through a second time, the cylinder has become so light that it shoots off into the air; Sidelburg concludes that his invention can be used to create metal balloons. Next, the inventor uses the machine on a laboratory baboon, which grows in size but continues to leap about with great agility.

Sidelburg’s final experiment is to test the machine on himself. In his excitement, however, he neglects to chain up the giant baboon, which begins tinkering with the machine just as Sidelburg enters it. The hapless inventor ends up swelling like a balloon and drifting into the sky, taking the machine with him, never to be seen again.

The protagonist states that he has access to Sidelburg’s plans and could feasibly re-build the machine, but decides against it: “Nature had a way of visiting dire punishment upon importunate mortals who seek to pry too deeply into her secrets.”

Another story of a faulty invention, this time one that goes into a great deal of detail about its theoretical underpinnings. Bob Olsen clearly had a great interest in the notion of a fourth spatial dimension, and explored the idea in further stories for Amazing.

The Moon Pool by A. Merritt (part 2 of 3)

Dr. Goodwin and his fellow explorers find themselves in the subterranean home of a lost race. Norwegian Olaf expresses fear that they are in the “Trolldom and Helvede” of Norse legend. Larry O’Keefe, an Irishman familiar with stories of leprechauns and banshees, feels more at home in this land of green dwarfs and mysterious, alluring women.

Dr. Goodwin and his fellow explorers find themselves in the subterranean home of a lost race. Norwegian Olaf expresses fear that they are in the “Trolldom and Helvede” of Norse legend. Larry O’Keefe, an Irishman familiar with stories of leprechauns and banshees, feels more at home in this land of green dwarfs and mysterious, alluring women.

The ruler of this cavern world, the priestess Yolara, is beautiful but ruthless. She executes a convict using a ray, destroying his body and leaving only sparkling lights behind; the explorers offer a scientific explanation for her apparently magical abilities, deducing that the ray caused vibrations in the man’s body that reduced him to his component electrons. They also take note of the fact that, as powerful as Yolara’s weapon may be, it is not as fast as O’Keefe’s handgun.

Another, perhaps more dreadful fate met by some of Yolara’s victims is to be sacrificed to the Shining One, the amorphous entity known to the explorers as the Dweller in the Moon Pool. Those thrown into the clutches of this being are reduced to a seemingly catatonic state between life and death.

Just as H. Rider Haggard’s Ayesha fell in love with Leo Vincey, Yolara takes a liking to Larry. Believing him to be divine, the priestess lets him in on her long-term plan: she hopes to send her people on an invasion of the surface world, armed with rays, invisible soldiers, gravity-destroying bombs, and the powers of the Shining One. Hearing of this, Goodwin glimpses “a vision of an Apocalypse undreamed by the Evangelist”:

A vision of the Shining One swirling into our world, a monstrous, glorious flaming pillar of incarnate, eternal Evil—of peoples passing through its radiant embrace into that hideous, unearthly life-in-death which I had seen enfold the sacrifices—of armies trembling into dancing atoms of diamond dust beneath the green ray’s rhythmic death—of cities rushing out into space upon the wings of that other demoniac force which Olaf had watched at work—of a haunted world through which the assassins of the Dweller’s court stole invisible, carrying with them every passion of hell—of the rallying to the Thing of every sinister soul and of the weak and the unbalanced, mystics and carnivores of humanity alike; for ell I know what, once loosed, not any nation could hold this devil-go for long and that swiftly its blight would spread!

Between them Goodwin, Larry and Olaf represent a mixture of American can-do attitude and Old World romanticism; their German companion von Hetzdorp, meanwhile, embodies something less wholesome. He strikes a deal with Yolara to help her on her plan for world domination, offering her the backing of his home country.

Merritt later revised the story so that von Hetzdorp became a Russian Bolshevik named Marakinoff. It is the earlier version that was published in Amazing, although even this acknowledges fears of Communism when Larry mentions that “the Bolsheviki are only pulling babes” compared to the invisible dangers of the hidden world. Published months after the close of World War I and less than two years after the Russian Revolution, The Moon Pool unmistakeably reflects the anxieties of its time.

But the heroes have one ray of hope. They learn that Lakia, a handmaiden, seeks to rebel against Yolara’s rule, aided by her dwarfish uncle Rador and an army of frog-men. And so Goodwin, Larry and Olaf (the last of whom considers Lakla to be the Jomfrau – the White Virgin of Trolldom) lend their support to this nascent resistance…

Discussions

The letters section plays host to another round of debate. Dady A. Chandy from Bombay lists his favourite stories, in the process giving an indication of the magazine’s international reach. George W. Graham gets into an argument with Hugo Gernsback about whether or not a man in a vacuum can move by kicking his feet. Clair P. Bradstreet expresses unease at a contemporary bill to bar the teaching of evolution in Maine schools. Aaron L. Glasser writes in to say that Samuel M. Sargent Jr’s “The Telepathic Pick-Up” may be coming true, as Prof. Cazzamalli of the University of Milan has reportedly developed a radio set capable of receiving radiation emitted by the human brain. Gernsback throws cold water on this notion by pointing out that, although Cazzamalli’s alleged experiments have been reported in contemporary media, nobody has ever managed to trace such an individual.

Edward J. Ludes, chief announcer of Radio KYA, offers some humorous thoughts about adherence to facts in fiction. “I have found that most persons afflicted with a touch of science,” he states, “have become addicts to fact… fact does not concede to imagination even though imagination will concede to fact. This makes the victim rather cold-blooded, with a tendency to be heartless.” He praises Amazing Stories for achieving a balance between fact and imagination, and shows particular fondness for Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The Land that Time Forgot. “In this story, one gets a little of the human angle which is so desirable; human feelings, human sufferings, of a real physical nature which we can all understand”. Jack Lea Harper, meanwhile, lashes out at critics who exhibit “an absurdly infantile prejudice against certain types of stories.” He argues that literature has two functions: “To amuse temporarily, and to serve as the record of human thought. The most important part of the last mentioned function is the stimulation of creative thought. I consider it unworthy of Amazing Stories to appeal to the passing whims of a distraught reading public seeking only a new and strange diversion.”

Amidst all this, the favourite topic of the month is clearly T. S. Stribling’s “The Green Splotches”.

“’The Green Splotches’ really deserves no place in this magazine” complains Edward J. Ludes. “This story treats on something that is impossible: namely; ‘Plant men that can talk.’ Where do they get their lungs?” Miles J. Breuer liked the story, but likewise tripped up on the conception of the alien plants; he dismisses the idea that such beings would be humanoid, and gives a lengthy description of what a sapient plant might actually look like. “Putting these beings into human form is a bit of anthropomorphism that is so characteristic of scientifiction”, he writes. “We can’t break away from it; we merely saw at our bonds and sever a thread at a time; we still put a human form on everything.” W. A. Young, similarly, criticises the biology of the plant-men.

Questionable as the story may have been to these readers, Miss I. K. writes in to ask if the events of “The Green Splotches” actually occurred: “Can it be possible that men from some other planet have visited our earth? I can hardly believe it, but as the Nobel Prize was awarded to them it must have been a true account.” The editor patiently explains that a character winning a Nobel Prize as part of a fictional narrative does not mean that the narrative in question is true.

And finally…

As well as a drawing by J. M. de Aragon depicting ignorance, fanaticism and cruelty as “three prediluvian monsters—man’s soul eaters”, the issue runs another poem by Leland S. Copeland: “Secrets Never Told”.

As well as a drawing by J. M. de Aragon depicting ignorance, fanaticism and cruelty as “three prediluvian monsters—man’s soul eaters”, the issue runs another poem by Leland S. Copeland: “Secrets Never Told”.

How did you mingle your atoms,

Formign the primitive cell,

Oxygen, Hydrogen, Carbon,

How did you manage so well?

Whence came the wonderful essence,

Life of the ages to be?

Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Sulphur,

Whisper your secret to me

Brought from the wreck of a planet,

After a keenly cold ride

Found life at last resurrection,

Out of a meteor’s side?

Or driven by light through the ether,

Woke it to thrive on the earth?

Chromatin, Protoplasm,

Tell me the truth of your birth.

Perhaps on the globe life was hiding,

Scattered in rock and in air;

Braving the heat of the hollows

Long ere the ocean was there;

Waiting the cycles the moment

To gather itself and be born.

Water, you mother of being,

Sing of the soul at its morn.