I was 8 years old, and I had gotten my greedy little hands on a copy of The Hobbit. I read it by nightlight early in the morning before my family awoke. The Lord of the Rings followed shortly after, and I even wrote my grade five book report on the plot structure of the Fellowship. One of the proudest moments of my childhood was when I completed that book report, a loving caricature of Frodo and his crew. It coincided with my first major social rejection.

My classmates openly mocked my enthusiasm for magic and fantasy; they also refused to believe I had actually read the books. Looking back, I understand. Most kids favoured slim paperbacks printed for little hands, while I needed both arms to carry my mother’s copy of the Tolkien trilogy. Born in a poor neighbourhood of a conservative, Catholic town, I suppose I looked pretentious, especially since most of the kids were reading Archie comics. I was so excited to discover Tolkien’s world of elves, wizards, and magic, one so much like my fantasy life in the alleys and backyards of Saint John, New Brunswick. Under every rock was a salamander for a spell; in every dark cloister was a wizard’s cave.

About that same time the early camaraderie of my childhood began to fade, replaced by the stratification of the school yard. In its place spawned a hierarchy of jocks, cools, nerds, and nobodies, ultimately separated into rich kids and poor; welfare bums, they were called, those left behind the spreading societal concern for the most expensive shirts or basketball shoes, and the supremacy of soccer over books. When the inevitable battle lines were drawn over a game of King of the Hill or Red Rover, I was left out, or pushed to the loser’s crew. Everyone knew what the heroes were supposed to look like back then.

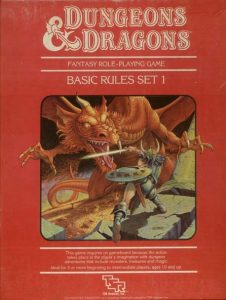

Around the same time I discovered Dungeons & Dragons (D&D), and I remember rolling up my first thief, Falcon, in class one day with an older friend’s help. That’s when the trouble started. With puberty pressing in, I recognized that many of my peers were choosing cool conformity over creativity, but I never imagined that I would also be choosing Satan over Christianity in that same process.

I remember the rumours. My mom had heard about it on the evening news — the Satanic panic of the Reagan era. Allegedly, kids had been playing a live-action form of D&D in a steam tunnel and their fantasy world had bled into the real one. They had stabbed each other with their fake swords, poisoned each other with their magic potions, and fallen prey to their imagined monsters — or so the rumours said. There was some truth to it. James Dallas Egbert III had attempted suicide in the utility tunnels beneath Michigan State U. Sadly, he eventually succeeded, though without any overt connection to D&D, just an overbearing mother and tons of stress. The theme of many of these rumours was similar: An impressionable youth, usually a white male, with “social problems” had confused fantasy play and reality, leading to tragedy. It was a hard sword to swallow. My growing fascination with the world of Fantasy books and D&D was being set up by the media as evidence of occult influences, even Satanic plots, but I felt I had no choice. My fantasy world informed my identity and filled my dreams. It showed me my future as writer, gamer, freak?

As W. Scott Poole suggests in Satan in America: The Devil We Know: “The ‘sword and sorcery’ genre became for American teens of the 1970s and 1980s what ‘cowboys and Indians’ had been for the 40s and 50s.” Looking back with adult eyes, it is no wonder that my mom succumbed to the rumours. A 2007 Harris poll suggests that more people in America believe in the physical presence of Satan on earth than they do in evolution, but that was the 80s, and the American Christian establishment also feared hidden messages in Heavy Metal music. Rumours of “backwards masking,” were rampant, infecting the minds of parents across the continent. According to Poole, Jacob Aranza, a Louisiana evangelist, had attacked musical acts like Ozzy Osbourne and the Eagles, claiming that even “Hotel California” contained Satanic messages. What chance did Fantasy or D&D books have with their provocative paratext?

Ostracized at my Catholic elementary school, I was regarded with growing suspicion by my parents. They looked on my recent acquisition from a family trip to New Hampshire — the AD&D Monstrous Compendium, a monster manual for gaming —with the horror of a faithful parishioner who has just seen her beloved preacher smoking reefer through a baby’s skull. Crumbling beneath the pressure, I retreated into my books, rejected for expressing joy over one of the first genuine fascinations in my young life. I remember reading Guy Gavriel Kay’s The Summer Tree around 1985 even though I could hardly understand the words. I remember my eccentric uncle Edgar’s vast collection of Fantasy and Science Fiction paperbacks, which he might lend me if I begged, though somewhat grudgingly. I first spied Raymond E. Feist’s Riftwar Saga in his bookshelf, and drew strength from its humble protagonist Pug as he fumbled his way into wizardry.

My uncle also owned an Intellivision game system, which featured a D&D game that used more than 4K of ROM — a true, state of the art, imagination station. When my mom came home one day with a Commodore 64, a 300 baud modem, and a copy of the legendary Ultima III, I fell for her 8-bit gambit like a drunken dwarf on a treasure chest. I have played Fantasy computer games ever since. Just look at this sexy cloth map. They don’t make ’em like that anymore.

I played Ultima on the computer with my one friend, thereby beginning what my mother hoped would be a transition away from that horrible, occult D&D game into something more healthy and productive, something like a future career as a programmer or accountant. Little did she suspect. By grade 6 I had friends across New Brunswick who I had met through that archaic 300 baud, dial-up modem. The proto-internet phenomenon known as Bulletin Board Systems (BBSs) were everywhere, even in the woebegone reaches of Saint John’s suburbs. “Atari Express” and the “Fundy User’s Group” hosted elaborate forums for whatever user’s wished, and it didn’t take me long to start my first online D&D game: The Arch of Demons. It became my first foray into Fantasy writing, but not gaming, because I admit that I rolled no dice, calculated no hit points. But still, the vorpal blades went snicker-snack every day after school, when I rushed home to write page upon page of replies to the stalwart group of adventurers who played the Arch for the better part of 6 months. My online campaign consisted of my one friend who played a dwarven healer named Sylvan Seraph, a newspaper journalist who played a wizard named Gilthanas, a real-life Wesleyan priest who played a paladin (go figure) named Leonidas, a university student who played a ranger, and his girlfriend, the warrior. I called myself Grim Reaper: Dungeon Master. While the details escape me, I do recall that it took several months for my players to realize I was just a kid. Then they commended the achievement and told me they were saving the story for a future D&D module, a kind of prepackaged game campaign. It was the proudest point in my life.

The glory faded quickly. Leonidas had contacted me online and suggested a proper meeting and a tabletop game after the Arch eventually collapsed. Unbeknownst to my fretful mother, my friend and I had travelled to the next town — a lifetime away when you are 12 or so — for an afternoon of swords and sorcery in a roadside trailer. Enroute, Leonidas explained how the church frowned on D&D, and since he was a pastor, we should keep the whole trip quiet and never mention that he was involved, and would we like to hear more about his Youth Group retreats? They were full of nice young guys like us who would love to get to know us, we could drop by anytime… And then there was his beautiful wife who looked on silently, smiling benevolently, cheering on our enthusiastic d20 rolls and wincing sympathetically when we took damage. When my mother learned of our little journey with a “friendly Wesleyan pastor and his cute, young wife,” the axe fell suddenly, permanently on my childhood passion.

She offered me an ultimatum: Take $100 dollars (a fortune in the 80s) in exchange for all my D&D materials, to be returned when I was older, or else death, or worse. I was horrified. My own mother, who had once encouraged me towards my fantasy fascinations out of sympathy for my outsider status as a nerd-against-the-herd now asserted her indomitable will against me, crying, begging me to stop the madness. No more priests, dark magic, Satanic tomes, no more…

I took the money.

Now I want my imagination back.